John Paul Stevens, a moderate midwestern Republican and former antitrust lawyer from Chicago who evolved into a savvy and sometimes passionate leader of the Supreme Court’s liberal wing and became the third-longest-serving justice on the high court before his retirement in 2010, died July 16 at a hospital in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. He was 99.

The cause was complications from a stroke that he suffered yesterday, according to an announcement from the Supreme Court. The only justices who served longer were William O. Douglas, whom Justice Stevens replaced in 1975, and Stephen J. Field, a nominee of President Abraham Lincoln who served for much of the late 19th century.

During his 35-year tenure, Justice Stevens left his stamp on nearly every area of the law, writing the court’s opinions in landmark cases on government regulation, the death penalty, criminal law, intellectual property and civil liberties.

Justice Stevens also spoke for the court when it held presidents accountable under the law, writing the 1997 decision that required President Bill Clinton to face Paula Jones’s sexual harassment suit, and the 2006 opinion that barred President George W. Bush from holding military trials for prisoners at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base without congressional authorization.

But it was in his frequent dissenting opinions that Stevens set forth a view of the law that seemed increasingly – but not automatically – liberal as the years went by and as the court itself shifted right.

A strong proponent of federal power, Justice Stevens sharply criticized the limitations Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and his fellow conservatives put on Congress’s power to define and remedy violations of federal law by the states.

In Bush v. Gore, the 2000 election case that helped George W. Bush win the presidency, Justice Stevens lamented in dissent that the five Republican justices who backed Bush would “lend credence to the most cynical appraisal of the work of judges throughout the land.”

In 2004, when the court, citing technical reasons, dismissed the plea of U.S. citizen Jose Padilla, who was being held incomunicado as an enemy combatant, Stevens blasted the majority for ducking issues “of profound importance.”

“If this Nation is to remain true to the ideals symbolized by its flag, it must not wield the tools of tyrants even to resist an assault by the forces of tyranny,” he wrote.

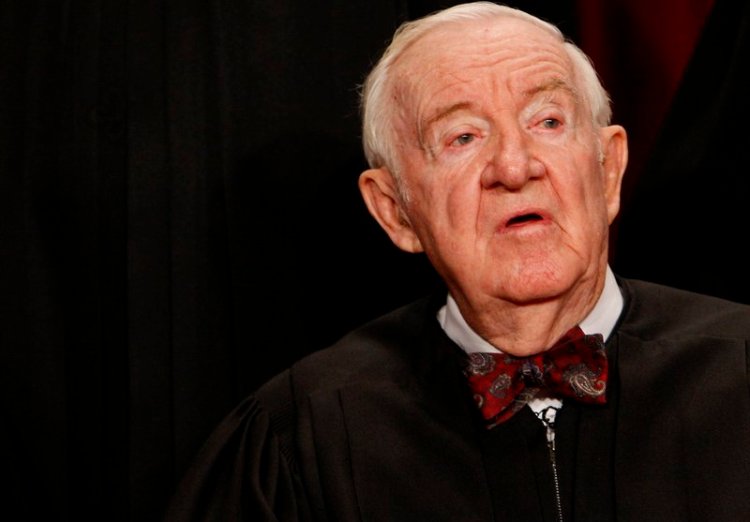

Justices Antonin Scalia, left, and John Paul Stevens chat during a ceremony at the Department of Justice in Washington on Nov. 3, 2005. Stevens, appointed to the court by President Gerald Ford in 1975, died Tuesday at the age of 99. Associated Press/Lauren Victoria Burke

Justice Stevens’s reference to the flag harked back to the 1989 dissent in which the decorated Navy veteran of World War II joined Rehnquist and other conservatives in dissenting from a ruling that recognized a First Amendment right to burn the American flag.

“The ideas of liberty and equality have been an irresistible force in motivating leaders like Patrick Henry, Susan B. Anthony, and Abraham Lincoln, schoolteachers like Nathan Hale and Booker T. Washington, the Philippine Scouts who fought at Bataan, and the soldiers who scaled the bluff at Omaha Beach,” Justice Stevens wrote in that case. “If those ideas are worth fighting for – and our history demonstrates that they are – it cannot be true that the flag that uniquely symbolizes their power is not itself worthy of protection from unnecessary desecration.”

A privileged, then turbulent childhood

John Paul Stevens was born in Chicago on April 20, 1920, the youngest of four sons. The family lived in Hyde Park, near the University of Chicago. His mother was a high school English teacher. His grandfather, James W. Stevens, was the founder of the Illinois Life Insurance Co. and owned the LaSalle Hotel, which Justice Stevens’ father, Ernest, managed.

In 1927, the family opened The Stevens Hotel in Chicago, billed as the largest hotel in the world at the time. Justice Stevens enjoyed a privileged childhood: He attended private schools affiliated with the University of Chicago, met celebrities such as aviators Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart at the hotel, and was lucky enough to be in the crowd at Wrigley Field on Oct. 1, 1932, when Babe Ruth hit his famous “called shot” home run off Cubs pitcher Charlie Root.

But the Stevens businesses went bankrupt in the Depression and Justice Stevens’s father, his grandfather and his uncle, Raymond Stevens, were indicted for alleged financial misconduct.

Shortly after the indictment, his grandfather James suffered a stroke and was excused from trial; Raymond committed suicide. A Chicago jury convicted Ernest in 1933 of embezzling $1.3 million. But his conviction was overturned in October 1934 by the Illinois Supreme Court, which sharply criticized the prosecution for bringing the charges, noting that “there is not a scintilla of evidence of any concealment or fraud attempted.”

The tragic experience reduced the formerly wealthy Stevens family to a middle-class lifestyle and taught Justice Stevens an enduring lesson in the harm that even well-to-do citizens can suffer from overzealous prosecution and other flaws in the justice system.

Justice Stevens graduated from the University of Chicago in 1941 with a bachelor’s degree in English and was starting to study for a master’s degree in the same subject when a dean persuaded him to take Naval intelligence training instead.

Justice Stevens joined the Navy as an intelligence officer on Dec. 6, 1941 – the day before Pearl Harbor. He would later joke that his commissioning had provoked the Japanese to attack, because they took it as a sign of American desperation.

He spent World War II at Pearl Harbor, working as a signals intelligence officer. His specialty was “traffic analysis,” the compilation of Japanese messages to discern patterns in communication that might help identify or locate enemy forces. Justice Stevens was awarded the Bronze Star for his work helping to decode a particularly difficult Japanese radio call sign.

Justice Stevens was on duty the day the the United States shot down Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s airplane, a strategic coup made possible in part because of interception of Japanese radio transmissions decoded by Naval intelligence.

The targeted killing of Yamamoto troubled Justice Stevens, who explained in a 2005 interview with law professor Diane Marie Amann that it sowed his first doubts about capital punishment, which he considered another form of deliberate killing by the state of a named individual.

After the war, Justice Stevens attended Northwestern University’s law school on the G.I. Bill and graduated in 1947. He made top grades and Prof. W. Willard Wirtz described him as “undoubtedly the most admired, and at the same time, the best liked man in school.”

At Wirtz’s urging, Supreme Court Justice Wiley B. Rutledge, a liberal appointee of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, hired Justice Stevens as a law clerk for the court’s 1947-1948 term.

Justice Stevens deeply admired Rutledge, whose most famous dissenting opinion came in 1946, when he wrote that the majority of the court was wrong to deny a petition for habeas corpus by Tomoyuki Yamashita, the Japanese general sentenced to death by a U.S. military commission in the Philippines for atrocities committed by his troops.

As a law clerk, Justice Stevens helped Rutledge draft another dissent in Ahrens v. Clark, arguing that the court was wrong to deny Paul Ahrens – and 119 other U.S.-resident Germans facing deportation for alleged Nazi ties – the right to file for habeas corpus.

Rutledge’s papers at the Library of Congress Manuscripts Division contain a memo by Justice Stevens in which he urges his boss to support a “fair hearing” in court for the alleged enemy Germans. “Otherwise,” Justice Stevens wrote, “the attorney general would have an unlimited power over aliens and citizens alike to deport upon a finding that the party was an enemy alien.”

After his clerkship, Justice Stevens practiced law in Chicago, developing a specialty in antitrust law. During the 1950s, he took a year off to serve as an aide to a congressional antitrust subcommittee that investigated professional baseball, and served two years as an aide to the Eisenhower administration’s Justice Department.

His first marriage, to Elizabeth Sheeren, with whom he had four children, ended in divorce. In 1979, he married Maryan Simon.

A son from his first marriage, John Joseph Stevens, was a Vietnam War veteran, and died of cancer in 1996 at 47. Justice Stevens later recused himself from ruling on a case involving war veterans’ exposure to Agent Orange, an herbicide linked to cancer and other diseases.

A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

In 1969, Justice Stevens was chosen as counsel to a special commission investigating bribery allegations against two justices of the Illinois Supreme Court. His investigation ultimately resulted in the justices’ resignation and propelled Justice Stevens to statewide fame.

At the recommendation of U.S. Sen. Charles H. Percy of Illinois, a moderate Republican, President Richard M. Nixon appointed Justice Stevens to the Chicago-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit in November 1970.

Five years later, again with the support of Percy and another Chicago friend, then-Attorney General Edward Levi, Justice Stevens received President Gerald R. Ford’s nomination to replace retiring Associate Justice William O. Douglas on the Supreme Court. He was confirmed by the Senate 98-0 and took the oath of office on Dec. 19, 1975.

‘May I ask you this?’

Justice Stevens quickly became known as an unpredictable thinker who showed his independence by having his law clerks separately review all petitions for certiorari to the court, rather than participating in the centralized “pool” made up of clerks from the other eight justices.

In frequent concurring and dissenting opinions, Justice Stevens explained the gradations of difference between his views and those of his colleagues, prompting a fellow justice, Potter Stewart, to quip that Justice Stevens “should have been called John Paul Jones – ‘I have not yet begun to write.’ ”

Sporting his signature bow ties, Justice Stevens was also known as one of the most courteous of the justices in oral argument, usually prefacing his questions by asking a lawyer, “May I ask you this?”

He more often reached conservative results in those days. In 1976, for example, he cast a fifth vote to permit states to reauthorize the death penalty just four years after the court had invalidated it. Later, he voted to strike down strict affirmative-action plans in university admissions and government contracting.

As the country, the court and the GOP moved right, Justice Stevens did not. He began to take a more favorable view of affirmative action, and fought to limit the scope of the death penalty.

In 2002, Justice Stevens wrote the majority opinion in a 6 to 3 decision that banned the death penalty for the mentally retarded.

In 2005, after years of condemning the death penalty for offenders younger than 18, which the court upheld in 1989, Justice Stevens won a fifth vote for his side.

As the senior justice in the majority, he assigned the majority opinion to the swing voter, Anthony M. Kennedy, a moderate conservative who had previously supported the death penalty for juveniles. In a concurring opinion, Justice Stevens defended Kennedy from a blistering dissent by Justice Antonin G. Scalia.

Justice Stevens also wrote the opinion for a 6 to 3 majority in a 2004 case in which the court rejected the Bush administration’s view that prisoners at Guantanamo Bay should have no opportunity to dispute their detentions in federal court.

All of these cases showed that Justice Stevens had developed from his earlier iconoclasm into a veteran who well understood the court’s internal dynamics, according to which the liberals needed the vote of at least one of the court’s centrists, often Kennedy or Sandra Day O’Connor, to form a majority.

Justice Stevens also established new law in areas that attracted less notice from the public but were no less important for their somewhat technical nature.

In 1984, for example, Justice Stevens wrote the court’s opinion in what became known as the Sony Betamax case, a ruling that cleared the way for widespread use of home videotape recording of television programs.

At the time, producers of television programs and movies were attempting to sue Sony for contributing to the alleged pirating of their products, but Justice Stevens wrote that Sony was not liable for its customers’ actions, because its video recorder had many other uses that were unquestionably legitimate.

“One may search the Copyright Act in vain for any sign that the elected representatives of the millions of people who watch television every day have made it unlawful to copy a program for later viewing at home, or have enacted a flat prohibition against the sale of machines that make such copying possible,” he wrote.

The same year, Justice Stevens set forth the principle that, where federal law itself is silent or ambiguous on a particular point, courts should defer to federal agencies’ reasonable interpretations of the law’s meaning.

The case was Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, and ever since Justice Stevens’s opinion, agencies have invoked “Chevron deference” to defend their regulations from legal attack.

In 2000, Justice Stevens wrote the opinion of the court in Apprendi v. New Jersey, ruling that judges could no longer increase convicted defendants’ sentences based on additional facts presented by prosecutors but not specifically found by the jury. Apprendi set off a revolution in criminal sentencing law that continues today.

And Justice Stevens was the author of what may have been the court’s least popular decision in recent years, a 5 to 4 ruling in 2005 in which it upheld the right of local governments to make property owners sell out in favor of private developers.

Though conservatives decried the decision, Justice Stevens defended it as an exercise of judicial restraint, a conservative legal principle. He argued that the result was dictated by precedent, and by deference to the decisions of legislatures that were still free to limit such property condemnations if they wished.

In 2012, President Barack Obama, who had chosen Solicitor General Elena Kagan to replace Justice Stevens after his retirement in June 2010, bestowed on Justice Stevens the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian honor.

Perhaps a more personal tribute occured on his final day on the bench, when lawyers and spectators throughout the U.S. Supreme Court chamber wore bow ties in his honor.

In retirement, Justice Stevens launched an active and, at times, controversial second career as a writer and commentator. He freely expressed agreement and disagreement with the court’s decisions, including recent ones. He published a memoir of five former chief justices he had known, as well as a second book recommending six constitutional amendments.

Justice Stevens’ list of proposed constitutional changes included several that would have enacted his dissenting opinions into the nation’s fundamental law, including support for campaign finance regulations and a proposed ban on capital punishment.

“I think there is one vote that I would change and that’s one – was upholding the capital punishment statute,” he told National Public Radio in 2010. “I think that we did not foresee how it would be interpreted. I think that was an incorrect decision.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.