July 4, 1786: Ten years to the day after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the residents of a part of Falmouth called the Neck achieve some independence of their own when their home area becomes incorporated as the separate community of Portland.

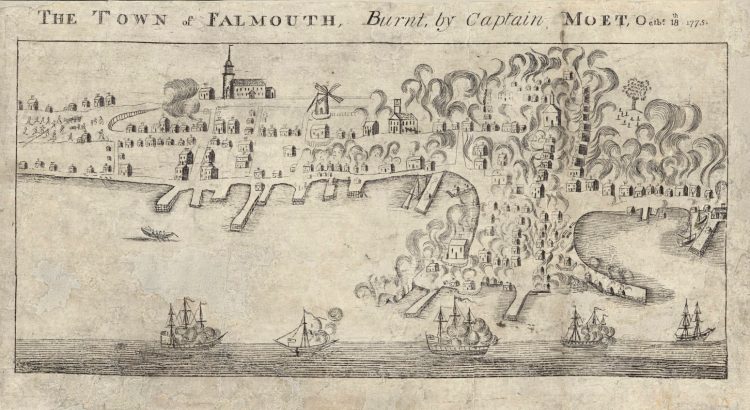

What is now downtown Portland remained largely in ruins for many years after a British bombardment destroyed much of it in 1775. Many people who lost their homes left the settlement, never to return. Others hesitated to settle there because the Revolutionary War with Britain continued until 1783, and nobody knew whether the British might strike again during that period.

What is now downtown Portland remained largely in ruins for many years after a British bombardment destroyed much of it in 1775. Many people who lost their homes left the settlement, never to return. Others hesitated to settle there because the Revolutionary War with Britain continued until 1783, and nobody knew whether the British might strike again during that period.

When peace finally was declared, however, an amicable meeting in May 1783 determined the terms of the settlement’s separation from the rest of Falmouth, and new settlers began to arrive rapidly. In 1784, the year after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, 41 homes, 10 stores and seven shops were built.

The first brick house, the home of Brig. Gen. Peleg Wadsworth, was built in 1785. The childhood home of 19th-century poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is still standing and is the property of the Maine Historical Society.

Because of an economic crisis, it takes three years from the time of the 1783 meeting for the actual separation of Portland to occur. The General Court in Boston – Maine still was part of Massachusetts then – approved the separation in May 1786, and it takes effect July 4. A month later, residents hold their first town meeting in the old meeting house.

The first federal census, conducted in 1790, records 2,240 residents in the new municipality. It is still smaller than York, Gorham and the remainder of Falmouth at the time. It quickly becomes Maine’s largest community, however, and it remains that today. In 2010, there are 66,194 residents counted in Portland.

The new town needs a name, of course. Some residents advocate calling it “Falmouthport”; others lobby for “Casco.” In the end, residents take the name that has long been used to describe the headland in Cape Elizabeth and the channel leading to the harbor, and they call it “Portland.”

The original Maine State House painted by Charles Codman in 1836. Courtesy of the Maine State Museum (catalogue number 72.19.56)

July 4, 1829: The cornerstone of the Maine State House is laid on Weston’s Hill in Augusta. The 150-by-50-foot building is completed three years later at a final cost of $138,991.

The project is dogged by cost overruns and a continuous effort on the part of Portland legislators to move Maine’s capital back to Portland.

July 4, 1866: A fire, apparently accidental and possibly caused by a firecracker, starts in a boathouse on Commercial Street in Portland.

It destroys about 1,800 buildings, leaves about 12,000 of the city’s residents homeless, and kills four people, according to a Portland Press Herald analysis of city death records.

Looking up Exchange Street from Fore Street. The Custom House appears almost undamaged, but the intense fire weakened the structure and it was taken down and replaced with a post office while the Custom House was rebuilt at its current location on Fore Street. Photograph by S.W. Sawyer — Photo courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

It is considered to be the largest urban fire in American history up to that date. Portland at the time is a city of about 30,000 people, ranking fourth in imports and fifth in exports among the nation’s seaports. The fire leaves most of it in ruins. It is the third time in its history that the community endures general devastation.

“The Fourth of July that year was celebrated with extraordinary fervor, with ringing of bells, firing of cannon, decoration of buildings, public and private, and a very long procession of military companies, fire department, civic bodies, floats and organizations making an imposing array,” historian Augustus F. Moulton writes decades later in his history of the city.

The fire, fanned by wind from the south and first reported about 4 p.m., quickly ignites a row of wooden houses on Fore Street. Wind carries embers to the Brown Sugar House complex on Maple Street, which is amply supplied with barrel parts and other combustible material. “The conflagration was soon beyond control” after that, Moulton writes.

Many factors hamper efforts to stop the flames’ advance. The city’s firefighting equipment consists only of a few steam engines and hand tubs, or hand pumpers. Firefighters can’t get to the crisis zone on the Commercial Street side, and flames and smoke on Fore Street make it dangerous to tackle from that direction. Wells and cisterns in the area soon run dry.

The fire creates a vacuum that sucks in more air, increasing the wind strength and prompting everything to burn with greater intensity. The draft fills the air with flaming objects, which spread out and set new fires, widening the area of destruction. Some people try to save their furniture by dragging it into the streets, but it quickly catches fire there.

The fire’s heat warps the iron horse car tracks embedded in the streets. Helpless fire crews try to limit the disaster by tearing down buildings or exploding them with gunpowder to create fire breaks. The inferno carves a wide path diagonally across the city from Commercial Street to Back Cove, roughly the same area burned during the British bombardment 91 years earlier, at the start of the Revolutionary War.

The fire burns through the night until it runs out of material to burn. The next day, from the Portland Observatory on Munjoy Hill, which escaped destruction, the scene looking westward, toward downtown, Moulton writes, is “a wilderness of chimneys, portions of brick walls that had not fallen and blackened remains of shade trees, while westerly, beyond were the green tree-tops, spires and houses of the undestroyed portion.”

The ruins cover about 300 acres. Buildings lost to the flames include the custom house, the post office, the 6-year-old City Hall, eight churches, eight hotels, all newspaper offices, and every bank, lawyer’s office, wholesale outlet, dry goods retail shop and bookstore. The fire also destroys half the city’s factories. Structures surviving the fire and still standing today include the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow house on Congress Street and the Abyssinian Meeting House on Newbury Street.

Monetary aid pours in from around the country, much of which still is recovering from the ravages of the four-year Civil War, which ended in 1865. Munjoy Hill, on the eastern end of the downtown peninsula, becomes a tent city housing refugees. Barracks are built quickly in various places for the same purpose.

The net financial loss is estimated at $6 million – about $106 million in 2019 dollars – or about a quarter of the city’s assessed valuation in 1866. The inability of insurance companies to meet their obligations resulting from such a large fire hampers reconstruction efforts, but rebuilding commences almost immediately.

Streets are relocated, widened and straightened. Noted Portland architect Francis H. Fassett, treating much of the ruined city as an unexpected gift of a blank canvas, designs a majestic new City Hall and many other public and private buildings that exude more grandeur than those they replace.

As a reaction to the water shortage during the fire, the Portland Water Co. is established in 1867 to bring water to the city from Sebago Lake. With the blasting of rock and laying of pipes compete, the first gravity-fed lake water arrives in the city amid great celebration on July 4, 1870, four years to the day after the fire.

July 4, 1896: A fire thought to have been started by a firecracker destroys the Augusta Opera House and several smaller shops and offices on its ground floor, including a grocery, a bank, a pharmacy and city government offices.

The Daily Kennebec Journal reports profusely on its front page the next day about the throng of people who filled Augusta’s downtown on the evening of July 3 and about Fourth of July fireworks that persisted late that night and into the holiday.

Changing the subject suddenly eight paragraphs into the story, the writer says, “The fire in Opera House block was so sudden, and so impressive, that it didn’t seem real.” Then the story reverts to describing holiday festivities. A story inside the paper gives more detail about the fire and speculates about whether the Opera House can be rebuilt.

The downtown building was erected in 1891 to replace the Granite Block, which had stood on the same site and burned in 1890. The structure later is replaced by the Capitol Theater, which burns in the 1980s and is demolished. A small municipal park now occupies the site.

July 4, 1975: Fire breaks out about 10:45 a.m. and levels the storied Poland Spring House in Poland just as its owners are planning to sell most of it to a Boston corporation that has been leasing it since 1972.

The building’s electrical system has been shut off for several years, so the sprinkler system is not functioning. Firefighters from Poland and eight other communities fight unsuccessfully to stop the five-story landmark’s destruction, but they prevent the flames from spreading to other buildings.

The hotel site was a tourist magnet for mostly wealthy vacationers since immigrant Jabez Ricker opened a boardinghouse in 1827 to exploit the fame and purported curative properties of Poland Spring mineral water. The hotel was built in 1876 and expanded later. In its heyday it had 325 guest rooms.

Vacant since 1969, the building is uninsured. The complex’s sale price is reported to be about $2 million. The sale closure deadline was to have been Sept. 1.

The last time the building was used was in 1970, when the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and 1,200 of his adherents occupied the building for a month.

Presented by:

Joseph Owen is an author, retired newspaper editor and board member of the Kennebec Historical Society. Owen’s book, “This Day in Maine,” can be ordered at islandportpress.com. To get a signed copy use promo code signedbyjoe at checkout. Joe can be contacted at: jowen@mainetoday.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.