Last in a series

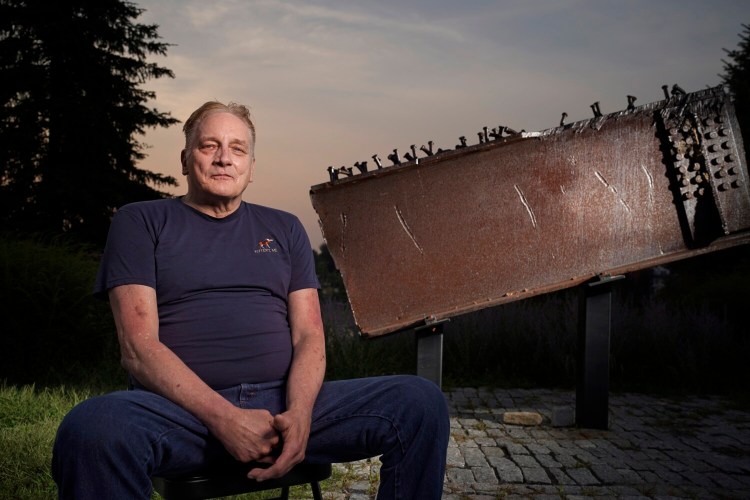

Looking across 15 acres of total destruction, Robert Glancy knew what he had to do.

Only days before, the terrorist attack had leveled the World Trade Center, leaving behind piles of twisted steel, debris and human remains. Glancy, then a 46-year-old ironworker from Kittery, had rushed to New York City with a friend to see how they could help.

For five weeks, Glancy spent 12 hours a day climbing across mountains of debris, first to help with the search for survivors and to recover bodies, and later to slice 100-ton beams so they could be removed.

He read the Lord’s Prayer every day before he climbed onto the pile and learned not to look closely when human remains were uncovered. He stuffed down his feelings while he worked and took comfort in kind words and hugs from strangers. When he stood alone on a beam, he felt like all of America was standing with him.

“It was the best thing I ever did in my life and it was probably the worst thing I ever did with my life,” he said during a recent interview from his home in Kittery.

Glancy, now 66, was working a job in New Hampshire when the planes struck and the towers collapsed. He knew he had the skills to help, so he and a friend headed to a union hall in New York hoping to volunteer. He was hired to work the most dangerous job of his life, and one that would leave him with health problems so severe he would be unable to work for much of the next 20 years.

“My whole life was gone the way I knew it before,” he said.

Glancy was a Vietnam-era veteran of the Coast Guard who liked to travel to bigger cities to work on major buildings and bridges. But, after he returned from New York, he found himself plagued with health problems that he says resulted from working at Ground Zero. He went back to New York each year for exams as part of a monitoring program for people exposed to toxins at ground zero. Doctors told him he has the lungs of a 120-year-old.

“From 2003 to 2015, I was laying in bed waiting to die. I was sleeping 18 to 20 hours a day,” he said. “I got winded if I said the Lord’s Prayer out loud.”

Glancy said his 9/11 experiences changed the way he interacted with people. For the first five years, he had no income and had to rely on others until he finally got some compensation through funds set up after the attack and workers’ compensation.

“I was always a little paranoid about other people. After (9/11) happened, everyone liked me. I decided to let them,” he said. “I learned how to ask for help. I wasn’t physically capable of doing anything and I needed to survive.”

In 2015, Glancy got a new inhaler that made breathing easier. He got out of bed and started living again.

“I guess I wasn’t ready to die,” he said.

Glancy, nicknamed “Big Bob” for his 6-foot-6-inch frame, finally felt well enough to get back to standup comedy, which he had performed twice a week in local comedy clubs before 9/11.

Standup comedy “keeps me engaged with life,” Glancy said. On stage, he mentions he worked at ground zero as he jokes about his injuries and ironworkers.

“You can tell he’s an ironworker. He’ll refer to third grade as his senior year,” he says.

Twenty years after the terrorist attack, Glancy still sees the impact of that day on the world around him. Right after 9/11, everyone was friendly, bonded together by a shared experience. Over the years since, there’s more hate and intolerance, he said. He’d like to see people return to caring about how others are doing.

“People would listen to your side of it and disagree, but there was no hatred and name-calling involved,” he said. “Maturity wise, we’ve gone downhill a bit. We forgot about how we got where we are.”

On the anniversaries of the attacks, Glancy doesn’t attend ceremonies or other events. He’s never visited the 9/11 Museum and Memorial in New York City.

But at home, where he has a few small pieces of steel from the towers, he reflects on the attacks, his experiences and the kindness of New Yorkers toward anyone who came to help.

And 20 years later, despite his health struggles, he has no regrets about helping.

“It seems like I threw my life away trying to save people I didn’t get to save, but that wasn’t the point. I don’t feel bad about what I did. I wish we had found some live people when I was down there,” he said.

“The life I have now is totally different. It’s not better or worse, it’s just different. I didn’t think it was a big deal at the time, but looking back I gave up what I had to save people I didn’t know.”

Read Sunday’s profile: Ticket agent struggles with guilt, trauma over two decades

Read Monday’s profile: Watching 9/11 attacks from classroom sparked social activism

Read Tuesday’s profile: Soldier from Portland knew that 9/11 attacks would change his life

Read Wednesday’s profile: For sisters of Mainer on doomed flight, ‘It’s the day our family changed forever’

Read Thursday’s profile: ‘They didn’t know me or what I would do for this country’

Read Friday’s profile: For teacher on fateful first day, ‘how it affected people is still palpable’

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.