Modern family lore had the pretty young woman falling through the ice at a skating party, swept downriver 200 miles away.

Really, Berengera Caswell was already dead when she was tied to a board, dropped in a stream and sent to sea.

Known around Saco as Mary Bean, she was an 1850s cautionary tale: For young women who start working in the mills, bad things await.

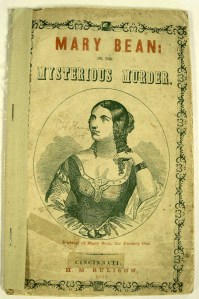

Elizabeth De Wolfe found Caswell’s story cast as a piece of sensational fiction in her husband’s rare books shop about 10 years ago.

Back in the day, its bright yellow cover “was a signal to potential readers this was going to be a racy, titillating, Gothic kind of tale. Sensational fiction usually involved murder, kidnapping or some sort of sexual indiscretion,” De Wolfe said. “I read it and thought, so Gothic, it’s got to be fiction, but I thought, you know, let me go look.”

It took De Wolfe, a professor and chairwoman of the department of history at the University of New England, 20 minutes at a local library to figure out the dead woman was real.

“This was, as they said in the newspaper, ‘a mystery most profound.’ And that’s what started this project,” she said.

Years of research into mill girls and social mores. Writing her own book. And the truth about Mary Bean.

Her body was discovered in April 1850 in Saco’s Storer Stream. Townspeople identified her as Bean, a newcomer who lived briefly with Dr. James Smith before her December 1849 disappearance.

De Wolfe said a man named William Long would tell police: “I don’t know anything about a girl named Mary Bean, but I haven’t seen my friend Berengera Caswell for several months and Dr. Smith told me she died of typhoid.”

Caswell and Long had worked at a Manchester, N.H., textile mill, she in the carding room and he in the machine shop. When he was fired, Long moved home to Biddeford. When Caswell found out she was pregnant, she came after him.

Both were about 20 years old.

“William turned to his mill supervisor for some advice, and the mill supervisor said, ‘I’ve got you covered; I have this friend,’ and the mill supervisor introduces William Long to Dr. James Smith,” De Wolfe said. “For $10 upfront, no real names, Smith will take care of Berengera.”

Abortion was legal, so that wasn’t an issue, De Wolfe said. But when his first attempts didn’t work, “by mid-December either Smith offered or Berengera begged for a more invasive procedure,” De Wolfe said. “She did abort but became horribly infected and a week later she died. At that point, it is a crime and that may be why Smith panicked.”

He bound and dumped her body, hoping it would be carried into the Saco River, and away to the sea. Instead, the board jammed on snow and ice.

Smith was found guilty of second-degree murder. On appeal, his court-appointed attorney, future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Nathan Clifford, got the crime reduced to manslaughter. He was sprung with time served.

“Smith had contracted tuberculosis, probably in prison, and within a couple of years of his release, was dead,” De Wolfe said.

Under “Mary Bean or the Mysterious Murder” and other titles, the tale was reprinted several times for an expanding audience. In it, the story suggests Mary met her death at the hands of two men after an astrologer foretold a violent end.

“Astrologers and fortune tellers were often a code for abortionists,” De Wolfe said.

She uncovered a dozen sensational mill girl stories from Saco and Biddeford set around the 1850s, some truly fictional, some spinning truth, like Caswell’s.

“All basically the same plot,” De Wolfe said. A young girl goes to work in the textile mills, and, “If she disobeys her parents, if she doesn’t act as a young girl should, she will certainly end up dead, insane, diseased or a prostitute.”

“Works of sensational fiction are really a mirror of social fears,” she said. “Young women for the first time are getting cash for their labor, and they very quickly understand their economic worth. They come to see themselves in a new light.”

That meant maybe a delay in marriage and motherhood. Maybe a dalliance that put her virtue, “of the utmost importance,” at risk.

“All of these issues are coming to play in this one story of a very real-life factory girl who passed through Saco, Maine,” De Wolfe said. “For me, what started out as a curious, titillating murder story ended up revealing very powerful and important cultural and socioeconomic issues from the 19th century.”

She spoke at Museum L-A last month. Her research hasn’t uncovered tales set at Lewiston mills. De Wolfe has a few theories: Girls of sensational fiction were typically Protestant, middle-class and native-born. She isn’t sure what she’d find if she dove into French-language writings of the day.

“We look back at our great-great-greats in the 19th century and I think we kind of have this image that everyone was just so nice and so placid, polite and virtuous, and they skated and then they died of cholera,” De Wolfe said. “But they were real people like you and me and us today.”

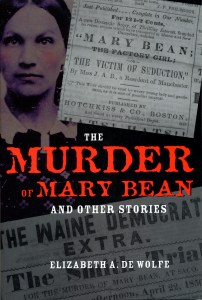

Signed copies of her book, “The Murder of Mary Bean and Other Stories,” are available at De Wolfe & Wood in Alfred.

Weird, Wicked Weird is a monthly feature on the strange, unexplained and intriguing in Maine. Send ideas, photos and most curious tales to [email protected].

Comments are no longer available on this story