BRUNSWICK— The Bowdoin College Museum of Art will offer visitors a rare glimpse into the artistry, rituals and beliefs of Bronze Age China.

“Along the Yangzi River: Regional Culture of the Bronze Age from Hunan,” an exhibit featuring about 60 bronze vessels and monumental bells cast in southern China between 1,300 BCE and 221 BCE, will be on view through Jan. 8, 2012.

New York City’s China Institute organized the exhibition with loans from the Hunan Provincial Museum, the premier repository of archaeological finds from the middle banks of the Yangzi River in southern China. Bowdoin College is the only other venue of this show.

Dr. Jay Xu, director of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and one of the curators of “Along the Yangzi River,” will give a lecture at 4:30 p.m., Thursday, Sept. 22, in the Visual Arts Center at Bowdoin College. A free reception and open house will follow at the college museum.

Among the most unusual objects on display is a 3,000-year-old rectangular, four-legged vessel decorated with large human face masks. “The faces of this so-called ding exude a spellbinding presence that has captivated viewers ever since a farmer deposited the object at a scrap metal yard 50 years ago,” Bowdoin College Museum of Art Curator Joachim Homann said.

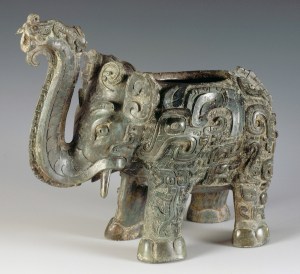

Also intriguing is a famous elephant-shaped vessel with intricate decorations that include a crouching tiger, bird, snakes and dragons.

Most of the objects in the show, however, allude to animals and vegetation in more restrained and abstracted forms, sometimes drawing attention to an animal mask only with a pair of raised eyes that transfix the viewer. Such decoration is characteristic of several bells, either hanging or standing upright and struck by the player at the rim with a mullet. Even when silent, the bells, decorated with boldly abstracted monster faces and tigers, are a testament to the authority and sophistication of their owners.

The presence of such unusual imagery in Chinese Bronze Age art is still unexplained.

“It is obvious, however, that the shapes and decorations animate and transcend the material and imbue it with a spiritual energy that distinguished these vessels as prized possessions of Chinese nobles,” Homann said. “For the elite, luxurious bronzes justified their claim to power and defined their status even after death.”

During the Shang (ca. 1600-1096 BCE) and Zhou (ca. 1046-256 BCE) dynasties, aristocrats were buried with enormous cachets of bronze objects that reflect their use in cooking, ancestor worship and court music.

This is the first exhibition to focus on the regional characteristics of Hunan bronzes. Artisans in the southern Chinese hinterland adapted with great skill the types of vessels from the Chinese Great Plains, some of which were traded to Hunan during the Bronze Age. But they did no feel restricted by their models. Animal-shaped bronzes and bells were a specialty of the south. This exhibition includes both, imported northern vessels that defined highbrow taste and the original, even odd, creations of the regional bronze-makers of the South. Many of these unusual bronzes were only recently brought to light through excavations.

Besides the Sept. 22 lecture and open house, the museum will host lectures by art historian Stephen J. Goldberg, Hamilton College (Oct. 13) and anthropologist Magnus Fiskesjo, Cornell University (Dec. 1). For more information, visit www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum.

This four-legged rectangular vessell, called a ding, can be seen along with about 60 other ancient Chinese artifacts in the “Along the Yangzi River: Regional Culture of the Bronze Age from Hunan” exhibit at Bowdoin College in Brunswick.

This bronze, elephant-shaped Zun vessell dates back to the 12th or 11th century BCE.

Comments are no longer available on this story