Three years ago, at the start of the fall semester at the University of Maine in Orono, a 20-year-old student was sexually assaulted by another student at a fraternity adjacent to campus.

The victim worked part time for the Bank of America call center in Orono. Her attacker also worked there.

Three days after the assault, the victim returned to work in tears and told an administrative assistant and a supervisor about the attack. She was sent home on unpaid sick leave, entitled to employment leave as a victim of violence.

Early in October she asked to return to work, telling Bank of America that she had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and was being treated for situational depression as a result of the attack. She asked that the attacker be transferred to a work station where she could not see him.

According to a Maine Human Rights Commission finding, her supervisor refused to accommodate that request but offered to instruct the attacker not to speak with the victim when she returned to work.

The attacker was later convicted of assault and providing liquor to a minor. UMaine established an on-campus safety plan to limit contact between him and the victim, but no safety plan was established by Bank of America.

The victim persisted in her requests for the company to develop a safety plan so she could return to work, including transferring her to a different work station, but she was denied.

She was fired Feb. 23, 2011.

On June 24, 2013, the Maine Human Rights Commission found reasonable grounds to believe the student was fired in retaliation for complaining about being forced to work in proximity to her attacker.

That retaliation is prohibited by Maine’s Whistleblower Protection Act.

The commission also found reasonable grounds to believe Bank of America discriminated against the student by not accommodating her PTSD disability.

That discrimination is prohibited by Maine’s Human Rights Act.

* * *

No employer in Maine, in either the private or public sector, is permitted to discriminate against an employee, threaten an employee or fire an employee for reporting a violation of law or rule to state or federal officials.

Employers cannot retaliate against an employee who reports a workplace practice that endangers workers’ health or safety, or against an employee who participates in an investigation or inquiry into violations of law.

Employees have worked under the safeguard of Maine’s Whistleblowers’ Protection Act since 1983 and under similar federal law since 1989, and while the overwhelming number of these complaints are dismissed, the number of cases that have merit is on the rise.

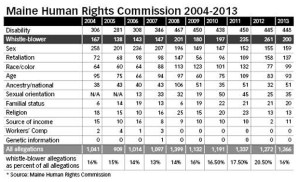

Nationwide, the number of whistle-blower cases the U.S. Department of Labor has found to have merit has nearly doubled since 2005. In Maine, the number of whistle-blower allegations filed with the Maine Human Rights Commission took a sharp turn upward in 2008 and has remained high, with 200 allegations filed last year.

One of those complaints was filed by former Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention official Sharon Leahy-Lind. Many of her allegations are now the subject of a federal lawsuit and a review by the Maine Legislature’s Government Oversight Committee.

The Maine Human Rights Commission, established in 1971, is a law enforcement agency responsible for enforcing Maine’s anti-discrimination laws.

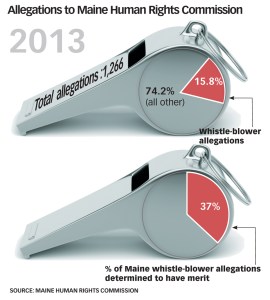

Whistle-blower retaliation complaints make up the second-largest category of allegations filed with MHRC — 15.8 percent of all human rights complaints in 2013.

Last year, commission investigators determined 27 cases contained reasonable grounds to believe the complainants’ rights had been violated. Of those 27 cases, 10 — more than a third — included whistle-blower claims of retaliation (see separate story).

According to commission Executive Director Amy Sneirson, whistle-blower cases result in a disproportionate number of reasonable grounds findings compared to other human rights cases, which is a trend the commission has tracked for a number of years.

MHRC has five full-time investigators, each carrying a load of about 80 cases, and seven other staff members who track cases and handle complainant calls. The investigation process for each allegation can often take years, and Sneirson said the workload has grown so much that the agency really needs another investigator to meet the public’s requests for review.

To conclude a reasonable grounds finding, Sneirson said, investigators have to determine the person filing the complaint was engaged in activity protected by the Whistleblowers’ Protection Act (such as reporting illegal activities), that the complainant was the subject of an adverse action (such as a job reduction, suspension or termination), and that there was a causal link between the whistle-blower activity and the action.

In the case of the UMaine student, investigators determined there was a link between the victim’s complaints to her supervisors and her firing.

* * *

In September, armed with the commission’s ruling, the student filed a complaint in U.S. District Court against Bank of America and Aetna, the company that handled requests for leave at Bank of America.

Citing violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Maine Human Rights Act, the student claimed Bank of America and Aetna failed to develop a safety plan for her return to work, which the law requires as a reasonable accommodation for her PTSD and depression, and fired her because of her disability.

She also claimed the companies violated Maine’s Personnel Files Law, which allows employees access to their personnel files, because when she asked for her file it was missing key records, including medical records and leave requests.

The student — who is still attending college — is being represented by Auburn attorney Rebecca Webber, who specializes in labor law.

Webber said that although it can be tough for people to summon the courage and energy to go to the Maine Human Rights Commission and confront an employer, her client gained strength from the fact that UMaine so quickly accommodated her situation and established a safety plan — including strictly limiting the time the attacker was allowed to be on campus and limiting the buildings he was allowed to enter.

In fact, Webber said, “UMO did everything right,” including kicking the attacker out of his fraternity.

The victim was also very quick to get therapy, and her mother has been supportive during the process.

According to Webber, when her client told her Bank of America supervisor she had been attacked and asked for accommodations, she was told that since her attacker hadn’t committed any banking crime under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, he would be permitted to remain at work.

* * *

Asked why the number of whistle-blower cases may be climbing, MHRC’s Sneirson said that sometimes a person who is filing another human rights claim will add whistle-blowing “in a kitchen-sink approach,” but in more cases, “people really, strongly feel that they have been targeted and have been punished for doing something right.”

In determining reasonable grounds to believe there was discrimination or retaliation, investigators rely on documents and interviews with the parties. And, Sneirson said, many times cases are decided on the credibility of either the complainant or the employer.

And sometimes, Sneirson said, a person will approach the commission with a complaint of unfair treatment, but the complaint falls outside the jurisdiction of the Human Rights Commission.

For example, last year, a state employee had a run-in with a co-worker, Sneirson said, “and it was very emotional and she was scared, but it did not fit within our statute. We all felt bad for her, but there was nothing we could do.”

In other cases, she said, “even though we’re limited in what we can do, we all feel this is a tiny piece of justice that we can offer” to determine whether a person’s rights have been violated.

Once the commission makes a determination, it often includes a recommendation for the parties to engage in settlement talks. If those talks fail, and the commission believes the victim needs immediate help, it has the option of filing a civil action in a superior court. Otherwise, it is up to the complainant to file suit.

* * *

Richard Hickson of Eastport took his case to superior court after the Maine Human Rights Commission found no reasonable grounds to believe his employer retaliated against him.

In that case, Hickson was fired from his job at the Domtar paper mill in Baileyville after he wrote an email to then-Gov. John Baldacci expressing concerns about safety issues he noticed during a visit to the mill by Baldacci and others on July 8, 2006.

Those concerns, Hickson said, were violations of mandatory security procedures of Domtar and Hampden-based Vescom Corp., the company hired to provide security at the mill.

According to court records, the governor’s party did not check in at the front gate, no one carried an emergency respirator as required and no one was wearing the required protective footwear. In fact, state Rep. Anne Perry, D-Calais, was wearing open-toed sandals.

Baldacci’s security chief sent Hickson’s email to Domtar, which forwarded it to Vescom, and Hickson was fired hours later when he reported for his shift. Asked why he was fired, Hickson said he was told Maine is an at-will employment state. Then, his supervisor handed him a copy of the email Hickson had sent to the governor. As Hickson turned to leave, he remembers that supervisor asking him, “What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know what he meant, but I said, ‘I’ll have to look into it,’” Hickson said.

The supervisor then replied, “Be careful what you do because Vescom might sue you.” Hickson remembers thinking: “Sue me for what?”

He spent the next several days at home, believing that what had happened was wrong but unsure whether he had any legal protection. He reached out to the American Civil Liberties Union of Maine, which didn’t handle his case, but did put Augusta lawyer David Webbert in touch with Hickson.

Hickson said he never set out to file a lawsuit after he was fired, but he wanted to make sure what happened to him didn’t happen to anyone else.

Webbert said Hickson was so reluctant to file the suit that he waited months to file a complaint with the Maine Human Rights Commission and years to file his superior court claim. Webbert even reached out to the governor to see if he could step in, but Baldacci never replied.

In deciding to file suit, Hickson said he wanted companies to know they can’t violate employees’ rights and he wanted employees to know they had protections under the law.

“You don’t do something like this for money,” he said, because the process takes years and can be very trying.

For Hickson, seven years lapsed between his firing and the supreme court decision in his favor.

The son of a police officer, Hickson said he was raised to be responsible and fair, and felt compelled to pursue his complaint because it was the right thing to do.

According to Webbert, that sense of justice is what drives most people to file whistle-blower claims. He said it’s very American to be altruistic and to firmly believe nobody’s above the law, so people tend to fight back when wronged.

The decision to fight can be difficult, though, Webbert said, because whistle-blowers are often far down in the company chain and risk retaliation from someone more powerful by speaking up.

“It’s human nature and it’s typical in the workplace that people in power don’t like to be criticized,” Webbert said, adding that underlings are often told, “You have a job; don’t be mouthing off.”

That’s particularly true in Maine because of its at-will employment status, which Webbert said many employers “take literally and think they can fire anyone for any reason, which is almost true. Except in whistle-blower cases.”

In 2010, Hickson filed a complaint in Washington County Superior Court claiming Vescom terminated his employment in violation of the Whistleblowers’ Protection Act. Following a three-day trial, and 30 minutes of deliberation, the jury returned a unanimous verdict in Hickson’s favor, and awarded him compensatory and punitive damages of $210,000.

That award was later reduced to $183,000, plus attorney’s fees.

According to Webbert, juries often find in favor of whistle-blowers because “in America, that you can get fired for sending an email to the governor strikes a chord.”

This particular jury, he said, “sided with the little guy against the big guys who thought, ‘OK. The governor doesn’t have to follow the rules.’”

Vescom appealed that verdict, and on Feb. 25, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court upheld the jury’s decision, finding a direct link between Hickson’s report of security violations and his termination.

According to Sneirson, the Maine Human Rights Commission does not track whether complainants file civil cases after their contact with her office, but she said it’s always interesting to read a media report of a jury verdict that matches the commission’s findings. And, she said, “It’s interesting to me when we get it wrong,” like in Hickson’s case.

Asked whether he believes he accomplished his objective to make employers aware that they cannot violate employee rights and let employees know they have protection under the law, Hickson said he believes he has. “I don’t want this to happen to anyone else.”

Maine law

Maine law requires that every employer post a notice explaining the requirements of the Whistleblower Protection Act and providing a phone number to call if an employee wants to report a violation.

If an employer does not do that, they are liable for a mandatory fine of $10 per day a poster is not visible to employees.

That fee cannot be waived.

Maine Whistleblowers Protection Act is contained in Title 26, Chapter 7, (5-B) §831-840

The federal Whistleblower Protection Act is contained in 5 U.S. Code §2302(b)(8)

Sample whistle-blower cases

These accounts are taken directly from 2013 Maine Human Rights Commission decisions.

Carol Pavone of Farmingdale was employed as an accounts receivable clerk at Standard Distributors in Gardiner from 1996 to 2010.

During her employment, other employees smoked throughout the facility and she regularly complained about smoking in the workplace and asked the office manager to have the smoking stopped.

In 2008, Pavone filed a complaint with police and that officer informed the company that smoking in the workplace was a violation of state law.

In October 2010, Pavone experienced chest pains and was diagnosed with coronary disease, and her doctor wrote a letter to the owner asking him to provide a smoke-free workplace.

Before returning to work, Pavone contacted the state Bureau of Health and the Attorney General’s Office to report the workplace smoking. The company was later fined $4,550 for violating the Workplace Smoking Act.

Pavone’s doctor approved her return to work for Nov. 15, but on Nov. 14 the company owner called and told her she was being fired because she had been out of work too long. The owner told the Maine Human Rights Commission that Pavone was fired because she requested a part-time schedule and the job required full-time hours.

On May 20, the commission found reasonable grounds to believe Standard Distributors retaliated against Pavone after she filed a complaint that the company was in violation of state law.

* * *

John Tracy of South Portland started working for Casco Bay Island Transit in Portland in 1986, the last 15 years as a senior captain. In 2006, after the company did not respond to safety concerns that Tracy and other senior captains raised, Tracy contacted the regional Coast Guard office to report Casco Bay was violating the federal 12-hour rule, which requires crew members to work only 12 hours in a 24-hour period.

After a meeting with Coast Guard officials, the company attempted to limit employees to working 12 to 13 hours in a 24-hour period.

Over the next six years, and at least seven more times, Tracy raised concerns with the operations manager about violations, including two incidents on July 3, 2012, when Tracy believed crew members violated the 12-hour rule. Three days later, Tracy found that a crew member had been assigned by that manager to work “grossly in excess of the 12-hour rule,” and told the operations manager he was done talking to him and intended to report the violations to the nonprofit company’s general manager.

In the course of a brief physical confrontation that ended when Tracy turned to leave the vessel, the operations manager tripped and fell.

Tracy was suspended from his job.

On Sept. 23, the Maine Human Rights Commission found reasonable grounds to believe that Casco Bay Island Transit retaliated against Tracy after Tracy announced he intended to pursue his concerns that the company was in violation of federal law.

* * *

Wesley Danforth of Winthrop was employed as a dental hygienist with the Kennebec Valley Dental Center in Augusta from September 2009 to July 2011.

On March 30, 2011, he filed a written complaint with the Maine Board of Dental Examiners, specifically naming the company’s executive director and a staff dentist and accusing them of poor quality of care and infection control, and Occupational Safety and Health Administration violations, including allowing dogs in the workplace.

Danforth was fired July 11.

The dentist has since left the practice.

In an internal company email dated May 11 that became part of the Board of Dental Examiners’ investigation, the executive director wrote that she decided to fire Danforth because she believed “he would continue to cause problems” and that he was a troublemaker, but she wanted to wait until after the board’s decision before taking action.

It was, according to the Maine Human Rights Commission investigators, one of the rare cases “with a smoking gun.”

The executive director wrote that she intended to fire Danforth two months before doing so, but the top three causes she cited in his termination letter all occurred after she wrote the email noting her intention to fire him.

On Sept. 23, the commission found reasonable grounds to believe Kennebec Valley Dental Center retaliated against Danforth after he filed a complaint with the Board of Dental Examiners.

* * *

Mary Boylan of Augusta started working for the Washington Hancock Community Agency in Milbridge in 1998 as a program assistant.

On April 13, 2011, Boylan had a verbal altercation with a co-worker and complained to the community action program’s human resources department that she feared for her safety.

When meeting with the human resources director, Boylan said her nerves were shattered, that the co-worker who yelled at her had a history of aggressive behavior and that she felt she needed to stay home until she could be assured of her safety at work.

Two days later, the human resources director told Boylan that she had conducted an investigation and found that Boylan had initiated the altercation, raising her voice before her co-worker did, and that there would be no disciplinary action against that co-worker.

Boylan was asked to decide whether to come back to work by April 18, and was fired when she didn’t show up.

Boylan had left a message for the human services director that she took April 18 off so she could see her doctor that afternoon; the doctor prescribed medication for severe emotional distress.

On Aug. 5, the commission found reasonable grounds to believe Boylan was fired after reporting unsafe activity in the workplace.

* * *

Kelly Roy of Old Orchard Beach was hired as the full-time office manager for the Old Orchard Beach Public Works Department in February 2010.

Over the next two years, Roy’s duties were extended to include processing accounts payable and payroll in the town’s financial department. In February 2012, the town hired a new manager and problems surfaced in the financial department, including bills not being paid on time, municipal contributions to retirement funds not being made and tax statements not being properly issued.

That month, Roy sent a letter about her concerns to her supervisor, believing the issues were violations of law. In that letter she noted that she wanted to stop her work in the financial department because of her concerns about how that department was being run.

After she sent the letter, Roy was threatened with a reduction in hours and with being fired, and town officials made disparaging comments about her at work and around town.

Six months after the finance director was hired, she left the job.

In early 2013, the town manager was fired.

On May 20, the commission found reasonable grounds to believe town officials retaliated against Roy after she brought forward her concerns about financial practices of the town. Specifically, the commission found that the town manager and finance director sabotaged her work after she filed her complaint and created a hostile work environment in an effort to force her to leave.

Roy left her job with public works last year.

* Source: Maine Human Rights Commission

Employment Retaliation Desk Aid

This aid has been prepared by John Gause, the former Commission Counsel at the Maine Human Rights Commission. He now has his own firm, Eastern Maine Law.

Securities Exchange Commission

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission actively encourages whistleblowing of possible securities laws violations.

Sean Kessey is the chief of the “Office of the Whistleblower,” and people who report violations that are found to have merit are entitled to receive a reward. In cash.

Generally speaking, the federal Whistleblower Protection Act is intended to protect the rights of federal employees, prevent retaliation and weed out wrongdoing in government, much like similar state laws across the country.

The SEC program is different. It incents people to report securities violations of $1 million or more by paying the whistleblower between 10 and 30 percent of the money recovered through any SEC enforcement action, according to the SEC. That can mean a substantial amount of money for the whistleblower.

For decades, the SEC has had programs in place that require employees to report financial misconduct, including audit discrepancies, but the whistleblower protections were only recently added.

The Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program was enacted in 2010 to bring greater accountability to Wall Street and provide more consumer protections in cases of deceptive financial practices by offering employment protection to whistleblowers from retaliation and offering cash awards to those who speak up.

Last October, according to the SEC, a Wall Street whistleblower was awarded more than $14 million after the agency was able to recover millions more in investor funds.

There were several awards made before that, but none for more than $50,000.

Under Dodd-Frank, the identity of whistleblowers is confidential.

More information

- Maine law

- Sample whistle-blower cases

- Employment Retaliation Desk Aid

- Securities Exchange Commission

-

a person who informs on a person or organization engaged in an illicit activity.

Comments are no longer available on this story