Despite the cold weather, there’s little paws in the action at Maine Wildlife Park in Gray.

The mountain lion purrs and rolls around on her back like a house kitty. The lynx watch, apathetic, from their high perch. The bear are asleep — sort of. And one stag bucks the trend to say an intimate hello to two rare visitors. It’s wintertime, but that doesn’t mean it’s all darkness and deep sleep at the Maine Wildlife Park in Gray.

It’s an early afternoon a couple weeks ago. Somewhere, not far off, one of the raptors is calling. Taking short, cautious steps across the icy parking lot, Curt Johnson reassures us: “You guys picked a good day for it.” The superintendent of the Maine Wildlife Park is right. On this day it’s mild, but still winter.

Which is precisely why we’re here. This park, a part of the state’s Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, sees more than 100,000 visitors in an average year. Home to 30 species, its mission is to educate the public about the fauna endemic to Maine, as well as about the mission and the role of the IF&W. However, the park is only open to visitors for about seven months out of the year, from mid-April to mid-November.

On this day, Johnson has promised to reveal what goes on at the park for the roughly 40 percent of the year when it’s closed to the public. And it’s no picnic.

As during the on-season, the primary job of the small winter staff is taking care of the animals who call the park home. “In that sense, this place is like a farm,” says Johnson. “The work is never done, there’s always mouths to feed. And someone has to be here, literally, every day of the year.”

Many, many mouths, as it turns out. The staff is responsible for lynx, bobcat, mountain lion, bear, coyote, moose, deer, woodchuck, raccoon, opossum, skunk and flying squirrel — and that’s just a portion of the mammals. There are also birds and reptiles.

Of the park’s roughly 80 animals, most live in the same outdoor environments summer and winter, taking the warm weather and rain with the cold weather and snow. But, says Johnson, “in general we make accommodations for all the animals in winter,” whether that’s laying down warm bedding or actually moving some species to indoor environments.

And the relative calm of the off-season means staff has time to upgrade and improve the facilities that house the animals.

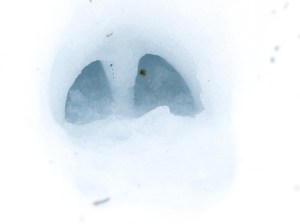

Johnson stands in front of the lynx enclosure — new as of last year. The sprawling exhibit includes rocky hiding spaces, climbing trees and a strip of snow-covered ground now well-worn with paw prints. The lynx is well-adapted to cold weather and, whether winter or summer, spends most of its day sleeping, using its wakeful hours primarily to feed.

“That was one of the objectives,” he says, “to give this a dense understory of spruce and fir, because that’s the forest they’re associated with up north.”

Johnson adds, “We try to make the habitat appropriate to the species while still creating viewing opportunities. And it’s really hard to do both.”

The lynx don’t seem too impressed by their thoughtfully designed enclosure, or by us. Perched on the highest limbs of their climbing tree, they survey the scene lazily. The male barely moves as we watch from behind a wall of glass.

“It wasn’t very many years ago that all of our mammals were in small, cage-like enclosures,” says Johnson. “We’ve covered a lot of ground in creating more naturalistic habitats.”

All different sorts of animals find their way to the park, though all are native to the state. And, as Johnson explains, all are “permanent non-releasables,” meaning that because of injury or upbringing they will never return to the wild.

While the lynx are nonplussed at our arrival, the mountain lion is excited to see us. “You’ll see her reaction to our presence,” Johnson primes us. “She’s going to be excited. She’s going to run up to us.”

His prediction is right. Before we’ve even reached the enclosure, she is calling to us in something not too different from a house cat’s meow. Her enclosure is large and modern looking, like that of the lynx. Built in 2012, it offers her space and a variety of terrain, but the cougar makes a point to get as close to us as possible.

“She was raised in captivity,” Johnson explains, and now she longs for human interaction.

That’s clear from her loud, guttural purring and the way she incessantly rubs her head and cheeks against the window that separates us. She reminds me of an oversized domestic cat in a particularly loving mood.

But, Johnson is quick to remind us why no one ever goes into her enclosure. Friendly as she looks, she could claw and chew me to pieces, literally. “In the case of the more dangerous” animals, such as the cougar, moose and bear, “we never go in there with them,” says Johnson. Meaning that the daily feedings, cleanings and any repairs must be done only after the animal has been secured in a smaller enclosure.

The lynx and cougar represent the majority of animals in the park who don’t hibernate during the winter.

While some animals, including the woodchucks and the brown bats, are effectively out cold for the season — “You could pretty much toss them around” without waking them up, says Johnson — most of the animals are either active or in a state of torpor.

Johnson explains: “If we were to approach a bear in their den, hibernating in the winter, that bear would be gone before we even get to it. They still have their senses, they would be very well aware that we’re coming.”

“Bear will have their young, they’ll even nurse their young” during winter, he says. And even those animals in hibernation or torpor require care and attention, whether that’s making sure food is available or regular monitoring to confirm all is well.

Sometimes that care is part of the hibernation process. For example, park staff do remove some animals from their outdoor enclosures for their safety. The skunk, opossums, flying squirrels and box turtle, among others, take refuge in a small building near the main office. Some of the reptiles are hibernated “artificially” in refrigerators or in the basement, according to Johnson.

The animals come inside rather than face the winter weather for fear that some may not survive Maine’s harshest season. However, Johnson said, animals are left in their wild habitats when it is believed they will be adequately protected.

The winter work falls to the park’s off-season “skeleton crew,” according to Johnson. From a summertime staff of around 15 — aided by more than 200 volunteers — park personnel shrinks in the winter to around five full-timers, which include two game wardens who live on the 200-acre property.

Considering the maintenance and facility upgrades that go on during the winter, it’s a large task for a small crew.

“We have all sorts of projects. Maintenance projects, construction projects. This is really the time of year when we catch up on things. So that really keeps us busy,” says Johnson.

That’s part of the reason why the park is closed for the five coldest months. But there are other reasons for the long break, he says, including safety and insurance concerns. Slipping as I walk from one enclosure to the next, I don’t need Johnson to explain what he means by “safety concerns.”

Moreover, he says, “the facility’s not set up for four-season operation.”

Nonetheless, Johnson is quick to mention the annual “winter photographer’s pass.” The only way, besides volunteering, for the public to experience the park in the winter, the pass “allows professional and amateur photographers to get exclusive access to our wildlife,” he says, and is available through the park’s website.

“That was our way of accommodating a small number of people that are willing and interested in coming in during the winter months,” says Johnson.

During our visit, we meet Brian Mackey, a Windham resident who began donating his time to the park after retiring several years ago. We catch Mackey in the middle of making a display case and he admits that most of his work is maintenance.

“I enjoy the animals, but I don’t take care of them,” he says, “besides putting up the fences.” Mackey enjoys the work. “I like it. Plus, I name my own hours,” he says with a laugh.

Mackey’s not the only one volunteering on this day.

In the winter “we don’t have a regular core of volunteers,” says Johnson. However, “we start up another (volunteer) program with the Windham Correctional Center,” which “sends a corrections officer and prisoners on a daily basis,” usually between two and five men. In exchange for their time, the volunteers get training in trades, such as woodworking and metalworking.

“These guys will learn a bunch of stuff,” says Johnson. “They take a lot of pride and ownership in these projects. When they get out of their incarceration they come back and show their family members and kids.”

As we walk past the bobcat enclosure, Johnson notes that the park continues to grow. “And we’re always trying to improve our facility, the exhibits for the animal, our displays and our special events.”

Johnson credits much of that to the work of Friends of the Maine Wildlife Park, the nonprofit fundraising arm of the park.

“They do a tremendous amount to help us out and to make our growth possible,” he says, including putting on the park’s annual flower show in May.

It’s clear that Johnson is already looking forward to spring. “When we open the park we’ll have this big kick-off event in May,” he tells us. “We open April 15 (assuming there’s no ice or snow on the ground), but we’ll have our grand opening of the lynx exhibit and a ribbon-cutting ceremony and dedication” on May 2, he says.

“And starting with that Saturday, every Saturday for the rest of the summer season we’ll host something special here at the park,” he says. (Check out the park’s website on www.maine.gov for a full calendar.)

On our way out of the park, we decide to stop and try to get some photos of the deer. The herd is congregating on the farthest side of the enclosure. When they see us they scatter, remaining far out of range. After a few minutes of us standing beside the fence, however, one curious buck approaches to investigate.

I put my hand up to the fence. He pushes a big, black, wet nose into it and takes a deep sniff. Then he begins to lick my knuckles intently. Perhaps I’ve been sweating. I’m not entirely sure. But at least, it seems, one member of the herd is already very excited to meet a new season of park visitors.

Max Mogensen is a freelance writer and owner of Anchor Arts and Communication.

Comments are no longer available on this story