Bug often found in firewood is wiping out ash trees to our south and west. Maine’s next on the menu.

A tiny, metallic-green bug is advancing toward Maine, hungry for ash trees.

It has killed tens of millions of trees in the United States and Canada and is uncomfortably close, only 35 miles away in New Hampshire. Some experts believe it is already here; we just haven’t seen it yet.

When we do, conservationists and entomologists say the damage will be massive.

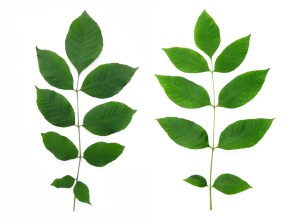

According to Jean Federico, education and outreach coordinator for the Oxford County Soil & Water Conservation District, the emerald ash borer is a “little, itty-bitty, teeny-tiny, beautiful green bug” with a singular appetite: north American ash trees, also known as white ash.

The bugs bore through a tree’s bark, leaving behind a tiny, V-shaped hole, Federico said. They attack ash trees almost exclusively, eating through the bark and into the trunk, disrupting a tree’s natural ability to draw nutrients upward. The death of the tree begins at the top, where it’s been starved, and works down.

Once infested, there’s little that can be done.

According to the Coalition for Urban Ash Tree Conservation at Purdue University, an infested tree will die within three to five years, and when it does, it will become brittle and fall in quick order.

In Maine, where large stands of ash trees grow in public spaces and on private land, the deaths will be pronounced, especially where the trees provide canopy along city streets.

And don’t think the state’s winter climate will kill this little green bug.

“This beast comes from Siberia, so it’s pretty much going to survive our winters,” according to Colleen Teerling, lead entomologist for the emerald ash borer initiative in Maine, which is a project of the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.

“We’re doing as much monitoring as we can,” Teerling said, “and if we find it early rather than late, we have a lot of management options.”

She added, “We’re never going to eradicate it, but we can manage it and slow down the spread to make it far less catastrophic.”

Maine has the advantage of knowing the experience from states already grappling with the pest. Teerling said that has helped, but it won’t stop the damage. “No place in the state is immune.”

Little hitchhiker

The emerald ash borer arrived in the United States — first spotted in Michigan — in 2002 and has been steadily munching its way across the country. Twenty-eight states have reported damage from this tiny insect, native to Asia and Russia, including most Midwest states and all but Vermont and Maine from the mid-Atlantic region up through the Northeast.

According to the Coalition for Urban Ash Tree Conservation, the pest was identified in Massachusetts in the summer of 2012 and in New Hampshire in the spring of 2013. The closest sighting to Maine is in New Hampshire, in Loudon and Concord, and experts expect it to cross the New Hampshire-Maine border soon, if it hasn’t already.

When it does, the towns and then the counties where it is found will be restricted, or quarantined.

That means no ash stumps, cuttings, logs or chippings may leave the area. For the towns and cities that must adhere to the quarantines, which require all infested ash be brought to a central location for storage, recycling or destruction, logistical and financial challenges arise.

New Hampshire quarantined its Merrimack, Rockingham and Hillsborough counties on April 1. All of Massachusetts was quarantined at the same time. And, according to Federico, the state of New York was quarantined May 1.

Researchers at Michigan State University say the emerald ash borer “is now considered the most destructive forest pest ever seen in North America,” likely carried here in ash used to crate and ship large overseas cargo. While adults can fly short distances between trees, and can be flung as many as 15 miles in a wind-swept thunderstorm, they’re most commonly transported by humans cutting and carting wood.

For example, Federico said, someone packing up their campsite in New Hampshire notices someone else left a pile of wood at a nearby site. “You’re being thrifty; you put it in your truck, you bring it home and you’ve done it,” Federico said. You’ve carried the insect to your own backyard, where it will feast first on your trees.

Scientists estimate the pest could kill as many as 8.7 billion ash trees once it has spread across the continent. Current treatment is very expensive and not entirely successful, and many municipal planners have pre-emptively cut millions of healthy trees, selling them while the wood still has value.

Managing the damage

In Lancaster, Pa., town officials adopted a 10-year management plan last year, opting to treat only the most valuable trees and to cut the rest, as many as 200 trees.

According to Karl Graybill, environmental planner with the Department of Public Works for the city of Lancaster, planning began years ago when city officials accepted that the emerald ash borer “was going to be here very soon.”

A tree inventory counted 300 ash trees along city streets and in public parks, and 70 of those trees were removed last year. A dozen more were recently cut, Graybill said, and the city is in the process of getting quotes to remove the remainder.

The bug arrived in Lancaster just over a month ago, on May 8 — years after planning began.

Graybill said the original cost estimate of the plan was $250,000, but they’ve been able to reduce some costs by having city employees cut some of the smaller trees.

“In two years, we’re going to start seeing dead trees,” he said, so the pre-emptive cutting helps spread the cost over time rather than waiting until the trees are all dead, forcing large-scale, expensive and tricky cutting.

Graybill said Lancaster has benefited from research done in Michigan and elsewhere where the pest has been active for years, and there is hope some trees can be treated and saved. “But,” he warned, “once you start treating, you’re treating forever,” and that’s a consideration in deciding public cost.

Towns that decide to treat trees are using a restricted-use pesticide called “Tree-Age” (pronounced triage), which costs more than $500 a liter.

That high cost is a consideration for a private property owner who may want to keep alive their trees, but if the treatment is unsuccessful and if there is any possibility the dying tree may fall in the public right of way, “we will have no choice but to send the owner an order to remove the trees,” Graybill said.

And that can be very expensive, particularly if it means dropping power lines and clearing streets during the work.

“In the public right of way,” Graybill said, “the trees are the responsibility of the adjacent property owner.”

The worry that property owners would delay tree-cutting was so high in Lancaster that Graybill said the city offered to remove 85 healthy street trees at no cost to property owners. “Or,” he said, “they could treat the tree themselves. Most opted to remove the tree.”

C-ash value

There is no value in ash once it’s infested, Graybill said, so property owners in Lancaster were easily convinced to cash in.

The resale value has also helped reduce municipal costs, he said, as wood products companies — including Kentucky’s Hillerich and Bradsby Co., which uses ash to turn its Louisville Slugger bats — buy the raw material.

In Maine, The Kennebec Company in Bath is collaborating with the Bath Community Forestry Committee to plant trees replacing ash. The company intends to use harvested ash for its hand-crafted cabinets and began planting replacement trees in 2014.

According to a town report, Ken Strainic of The Kennebec Company said, “We want to replace the trees that we use while also ensuring that Bath, our company’s hometown, has healthy and vibrant trees downtown and in public places throughout the city.”

In Lewiston, city arborist Steve Murch said ash trees do not make up a high percentage of street trees, and there is a generalized but not formal management plan in place to combat the emerald ash borer.

“We used to plant more ash in the downtown area because they’re a great street tree,” he said, but the city now is planting fewer trees, aware that they could become infested within the next decade.

The Lewiston-Auburn Tree Board has held a number of training and education sessions for the community, but Murch said it’s been tough to draw interest because the insect’s invasion is really not compelling to people until it becomes imminent.

He’s aware that elsewhere in New England, towns have pre-emptively cut ash to curb infestation, but, “I don’t see that happening in Lewiston,” he said. “Things would have to get very dramatic” before the city launched a harvest.

Instead, Murch has participated in a number of trapping programs to locate a stingless wasp called spathius argil, which feasts on emerald ash borers and nests in sandy soils found in ball fields. Wasps will take the borers back to their nests, so if the pest is found in ball fields, that means local trees are likely infested.

None have been found in Lewiston or Auburn.

Murch also girdled a tree last month, setting a trap for borers (see sidebar on the process), and plans to cut the tree down in the fall and send a test sample to the Forest Service to inspect for the insect.

Lewiston’s approach to the looming infestation, Murch said, is education and low-cost solutions to curb damage.

And there is hope for a cure in the years to come.

According to Maine entomologist Teerling, “There’s a huge amount of research going on, and the more time we buy, the more we can slow down the EAB when it comes into the state, and the better tools we’re going to have.”

While that may be so, said Kevin Sayers, state urban forestry coordinator for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, “even with that research, it isn’t like we can put the genie back in the bottle.”

And he should know.

Battle in Michigan

Sayers has been on Michigan’s front line of the emerald ash borer fight since 2002 when it was first discovered, believed to have hitchhiked in freight crossing the Great Lakes. Since then, he estimated, Michigan has lost 85 to 90 percent of its elm trees.

Early on, entomologists and arborists determined pretty quickly that eradication wasn’t a feasible option, Sayers said, and the goal became slowing the bug down.

“It’s all about detection,” he said. “If you think you might have it, throwing down kind of a buffer zone of a half-mile radius” by cutting a swath of ash may slow it down. “You have no assurances that you are going to eradicate it because you can’t always detect it,” he said, “particularly at low levels” when it moves into new territory.

His advice for Maine is to focus on firewood messages and warn people that transporting firewood means transporting the emerald ash borer.

“It’s always about repeating the message,” he said, because even though Michigan has delivered warnings for years, some people still aren’t aware of the danger and what they can do to mitigate it.

For landowners and towns, it’s important to survey land to see how much ash is standing, including how many trees are in public rights of way, to be able to manage the treatment and harvest.

Taking a “no-action” approach is the wrong move, Sayers said, because “the bug will get there at some point.”

Maine’s reality

Maine’s Teerling also encouraged people to think about managing the problem now rather than waiting until it arrives.

“There may be things in five years that we don’t know about right now,” in terms of research and treatment, she said, but in the meantime “we’re encouraging towns and businesses, if the trees are going to die or need to be taken down before they die, rather than turn them into wood pellets, get some value out of the trees.”

Federico went further.

“If people have a tree that they care a lot about, they can choose to take it down and have something made out of it,” such as a piece of furniture.

When the emerald ash borer arrives, it will be hungry, she said. “It happens so fast. There’s a period where it’s pretty level, just here, there . . . and then it just spikes.”

At the request of public officials, Federico has done some education and training outreach in some Oxford County towns, including Norway and Woodstock, and is ready to do more if asked.

In the early days of the infestation in Michigan, the state’s natural resources department was aggressive about cutting trees, but Sayers isn’t a fan of wholesale harvest any more. “It’s sad to say, but there was a lot of wood that got wasted, ground up” and destroyed, Sayers said.

By cutting “you’re losing a lot more than just that tree. You’re losing all of the benefits that that tree provides,” including ecological benefits of large trees with storm-water issues, along with the aesthetic loss to property value. Cutting is certainly part of the solution, he said, but it doesn’t have to be the first move.

Ash trees are still growing in Michigan, Sayers said, especially in Detroit, where trees were initially cut. The roots lay dormant, and some of those trees are now suckering, with new stems shooting up from old roots.

Other trees have demonstrated a natural immunity to the borer, and researchers are studying these “survivor” trees, Sayers said. That research opportunity “is another reason not to take down all the ash trees now.”

Communities must accept that the pest will be in Maine, he said, assess their risk by doing tree inventories, adopt management plans and endlessly repeat the message: Don’t move firewood.

Don’t move firewood

Forestry experts say the most significant action people can take to delay the emerald ash borer’s harm to Maine ash trees is to not bring wood, specifically firewood, into Maine. It may contain the invasive bug.

In 2010, recognizing the threat of emerald ash borer and the Asian long-horned beetle, the Legislature issued an emergency order restricting the transportation of firewood in-state for public safety.

That order has been consistently renewed, the most recent issued in April 2015.

All firewood brought into Maine is subject to inspection and potential confiscation by the Maine Bureau of Forestry or Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands.

Warning symptoms of infestation

• Dead branches in the upper canopy;

• New branches and leaves sprouting on the lower trunk and base of the tree;

• Vertical splitting in the bark; and

• Unusually aggressive feeding by woodpeckers that relish the emerald ash borer larvae under the bark.

Setting traps for the emerald ash borer

The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry is seeking volunteers to help girdle ash trees — set traps for the emerald ash borer — across the state.

Girdling is a process of stripping an area of bark from a healthy ash tree to stress it, making it more attractive for the ash borer. In the spring, the tree is cut down and the Ag Department and volunteers strip the remaining bark from the tree to hunt for the insect.

Girdling is typically done to trees that a property owner intends to take down anyway, according to Colleen Teerling, lead entomologist for the EAB initiative in Maine. “We’re sacrificing a few trees to, hopefully, save a large number of trees,” she said.

Girdling is typically done from early May through mid-June, and there’s still about a week left to get the work done in Maine. Volunteers interested in helping should contact Teerling at [email protected] or 287-3096.

For more information on girdling, go to www.maine.gov/dacf.

Beware of scammers

As the emerald ash borer moves East so have scammers, according to Jean Federico, education and outreach coordinator for the Oxford County Soil & Water Conservation District.

Scam examples include:

• People will knock on a homeowner’s door and offer to take down trees for a fee, much like driveway paving scammers. Homeowners pay in cash, but the tree is never taken down. Or, it’s taken down improperly, causing property damage. “They’re not licensed or insured and could leave you in a fix if something goes wrong,” Federico said.

• Someone at the door will offer to “treat” your ash trees to protect them from infestation. “They’ll sprinkle a little water around the tree, take your check and they’re gone,” Federico said. EAB treatment is an insecticide injection, is very expensive and must be done annually.

She urges property owners and city officials to be on guard. Once the emerald ash borer arrives in Maine, Federico said, “you’ve still got time to make choices, so talk to somebody who knows what they’re doing.”

A list of licensed arborists and the companies that employ them can be found at www.maine.gov.

Upcoming training to recognize and report EAB

The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry offers training for people interested in learning how to recognize, report and spread awareness of the emerald ash borer, an invasive tree pest first found in Michigan and quickly infesting ash trees across North America. All sessions are four hours.

The Forest Pest Outreach Project will provide materials for volunteers to continue outreach in their own communities.

The next training session will be held from noon to 4:30 p.m. Wednesday, July 22, at Hillgrove Community Hall in Whitneyville.

Additional sessions will be held on Tuesday, Aug. 25, at the University of Maine in Farmington and on Tuesday, Sept. 15, in York County (place to be determined).

FMI, or to register, contact Lorraine Taft, outreach coordinator for the Forest Pest Outreach Project, at 832-6241 or at [email protected]

If you think you’ve spotted the emerald ash borer or damage that may have been caused by the insect call the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry at 287-3891 or report the sighting here: http://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/caps/EAB/EABreportFORM.shtml

Comments are no longer available on this story