As far as I know, my dad has never particularly enjoyed cooking, and beyond loading the dishwasher (or rearranging the substandard loading of someone else), he ceded most kitchen responsibilities to my mom.

But he did make me breakfast. Every day.

And I don’t mean pressing the “toast” button or filling up a bowl with cereal. Every morning before school – all the way though high school – I had a hot breakfast waiting for me after I got dressed: eggs or pancakes or waffles, etc.

As with most childhood routines, you don’t realize what’s normal until you hear of others’ experiences. Every dad made Sunday omelets for the family by whipping eight eggs on the highest blender setting, right? Right?

In middle school, I watched as the parents of my carpool classmate hit the McDonald’s drive-through on the daily commute, but it wasn’t until my own kids reached school age – and I routinely forgot to get out a granola bar, much less hit “toast” – that I realized what a commitment preparing a daily breakfast was.

I’ve occasionally mentioned to my dad how remarkable that was – even then couched in some heartfelt sentiment such as, “Man, that was a ridiculous thing to do every day” – but I’ve never really asked him why he did it. And when I think about my own cooking – which, weekday breakfasts notwithstanding, is considerably more frequent and ambitious than Dad’s – I realize how little I actually think about cooking. I think about what I want to cook, the ingredients I have and those I need to buy, the time I’ll need to allot – and, of course, optimal beverage pairings. But I don’t spend that much time thinking about why I’m doing it. One could easily attribute that to, “you’re a man; you never think about why you do anything.” But I prefer to consider that the lack of thinking makes cooking an unfiltered expression of how I feel toward those I’m cooking for, or with.

I know Dad wasn’t savoring the pleasures of scrambling eggs for the third straight morning. And I’m sure he wasn’t looking forward to experimenting with new ingredients (although his blender omelets always included a few shakes of paprika, which might have been exotic for the upper Midwest in the late ’70s). But he often worked late, so that morning send-off was a reliable chance to influence his kids’ days. Given that, he was going to do everything he could in that limited window of direct contact to put his kids in the best position possible. So he wasn’t going to serve Lucky Charms when there was a blender available to mix pancake batter. Dad evidently didn’t believe in whisks; we’re lucky our bread didn’t get sliced with a circular saw.

There’s little doubt that preparing and serving food can convey nuanced messages for the cook who might otherwise be less expressive, particularly around those closest to him. The stoic who can’t tell his wife he’s looking forward to the weekend can spend his idle time planning a menu, and maybe Saturday night’s tapenade will convey the days of consideration that went into it.

My father-in-law truly enjoys cooking. Most of our time together involves vacations or holidays, and the celebration of the family evening meal begins long before anyone sits down at the table. I learned a lot of cooking techniques by volunteering for kitchen prep work, and after gently being instructed on the difference between “chopped” and “minced” in my early days as an interloper, I was charged with gradually increasing responsibilities. At a true rite of passage, I was entrusted with oven duties during our Cape Cod vacation pizza nights, which can include 11 different pies for upward of 20 diners. Shifting crusts from pan to stone to table, I felt a more profound level of acceptance. It was a particular satisfaction when my father-in-law’s cousin said he could probably get me a job in a South Philly bakery; I asked whether he knew about the state of the journalism industry and told him not to lose my number.

Of course, messages can get delivered in various directions, and when my kids turn up their noses at whatever I’ve made (a regular occurrence), the feeling of inadequacy is much more deflating than when they reject my advice or offers of help (another regular occurrence). But when I’m able to nearly replicate the black beans of a local Salvadoran restaurant – or even just when my son can’t wait to slice my near-weekly loaf of bread once pulled from the oven – there’s a purity of expression: “Here, I made you this. Enjoy it.” For those of us who can’t manage to build a treehouse, that’s something. And on those rare occasions of “Dad, will you make us . . . ,” it’s almost impossible to think anything but “Whatever you want.”

I look forward to the day my kids’ palates broaden, but until then, I take some satisfaction in conveying the idea that dads can do the bulk of a household’s cooking. This has been confirmed over past holidays, when my daughter and I have exchanged gifts reflecting our devotion to Michigan’s football team: I got her the quarterback’s jersey; she got me a maize-and-blue apron.

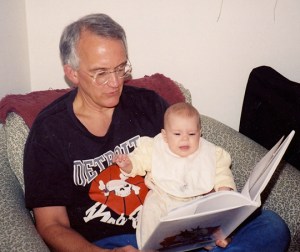

These days, when my folks visit to see their grandkids, I almost always make it a point one night to smoke some baby-back ribs. Dad makes a mess, filling up his plate with cleaned bones, pausing occasionally to say, “You know, your mother won’t let me eat like this.” (Good thinking, Mom!) I don’t think much about why I always make sauce and stock up on wood chips before their visits. For me, it’s an excuse to indulge, as my wife rarely eats pork. But when I can get the bark close to right, the meat pulls off the bone and Dad says, “Maybe just a couple more,” at some unspoken level he knows I’ve said, “Thank you.”

Comments are no longer available on this story