AUGUSTA — A bipartisan trio of state lawmakers hopes to shepherd to passage legislation that would allow terminally ill patients in Maine to end their own lives with a fatal dose of medication.

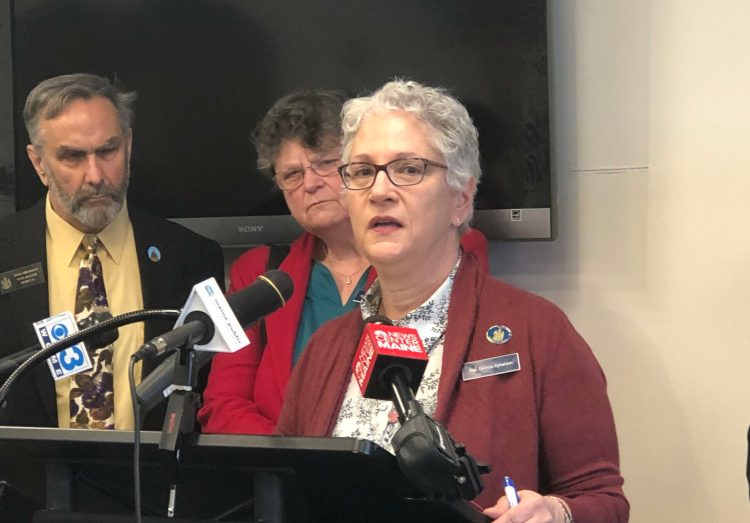

Rep. Patricia Hymanson, D-York, the House chair of the Health and Human Services Committee, a neurologist and the sponsor of the bill, said she was bringing the legislation forward again this session, despite previous bipartisan defeats of similar measures. The Health and Human Services Committee will hold a public hearing on the measure Wednesday.

The House last rejected the so-called “death with dignity” bill in 2017 with a 85-61 vote that crossed party lines.

The Maine Medical Association, which represents doctors before the Legislature, said in a prepared statement that it will not take a position on the bill. The association referred to guidelines developed by the American Medical Association, as well as a poll of MMA members which found that physicians were divided on the issue.

“While MMA will take no position on the central issue of physician-assisted death in such proposals, it will testify as needed on any provisions of such initiatives that might adversely affect patients or physicians and it will continue its long-standing advocacy for the best possible end-of-life care, including hospice care, for all residents of both urban and rural parts of our state,” the association said.

Hymanson said at a news conference Monday that she believes there is new momentum for the legislation. She pointed to a recent poll which found that 73 percent of Mainers favor the law change. Hymanson’s proposal is nearly identical to a law that’s been on the books for 20 years in Oregon.

She said New Jersey is also on the cusp of passing a similar measure and noted that a citizens initiative could go to Maine voters in November if the Legislature fails to adopt her bill.

After New Jersey, Maine would become the eighth state to allow terminally ill patients to end their own lives. The District of Columbia has a similar law.

Sen. Marianne Moore, R-Calais, a co-sponsor of the bill, said her father died of cancer in hospice and would have preferred to have control over his death.

“We watched him go downhill very quickly as his quality of life deteriorated rapidly,” Moore said. She said his pain was kept at bay with morphine, but he was incoherent and would have “been horrified to know he was wearing diapers.”

Another co-sponsor of the bill, Rep. Michele Meyer, D-Eliot, a nurse who serves on the Health and Human Services Committee, said most people hope for long and happy lives with a peaceful and painless death, but that’s not the reality for many who are diagnosed with a terminal illness.

“Sometimes the course is peaceful but often it is horrific,” Meyer said, “in spite of all the services, the medication and the expert care we have to offer.”

Hymanson said that, like the Oregon law, her proposal has several key requirements. Those seeking to end their lives must be an adult, have less than six months to live and have consulted with a physician and made at least three separate requests for life-ending medication, including two in writing.

Opponents in the past have raised concerns about the need for physician supervision at the time of death and a means to ensure that a person is not being coerced into suicide by family members seeking an inheritance or other financial gain. Opponents have also argued that giving terminally ill patients a means of escaping pain through death could erode their will to fight, and they might miss a medical breakthrough that could save their life.

Opponents include some conservative lawmakers who say the law would allow suicide to be normalized. They point to increased suicide rates in states like Oregon where similar laws were passed.

Testifying against the bill in 2017, state Sen. Lisa Keim, R-Dixfield, said she was concerned about that and about the possibility that the law would be expanded to cover other categories of people.

“It may be tempting to think that the parameters for eligibility, namely, diagnosis of a terminal illness with a prognosis of six months or less to live, are fixed and will never be broadened,” Keim said at the time. “It may be tempting to think that the allowances in these bills will only ever be for a small minority of the population. But this is not the case.”

The bill, L.D. 1313 is scheduled for a 9 a.m. hearing Wednesday in Room 209 of the Cross Office Building, next to the State House in Augusta.

Scott Thistle can be contacted at 791-6330 or at:

sthistle@pressherald.com

Twitter: thisdog

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.