Two respected giants of Maine’s trial courts have retired after long careers that shifted the way the state’s criminal justice system interacts with people who have addictions and mental illnesses.

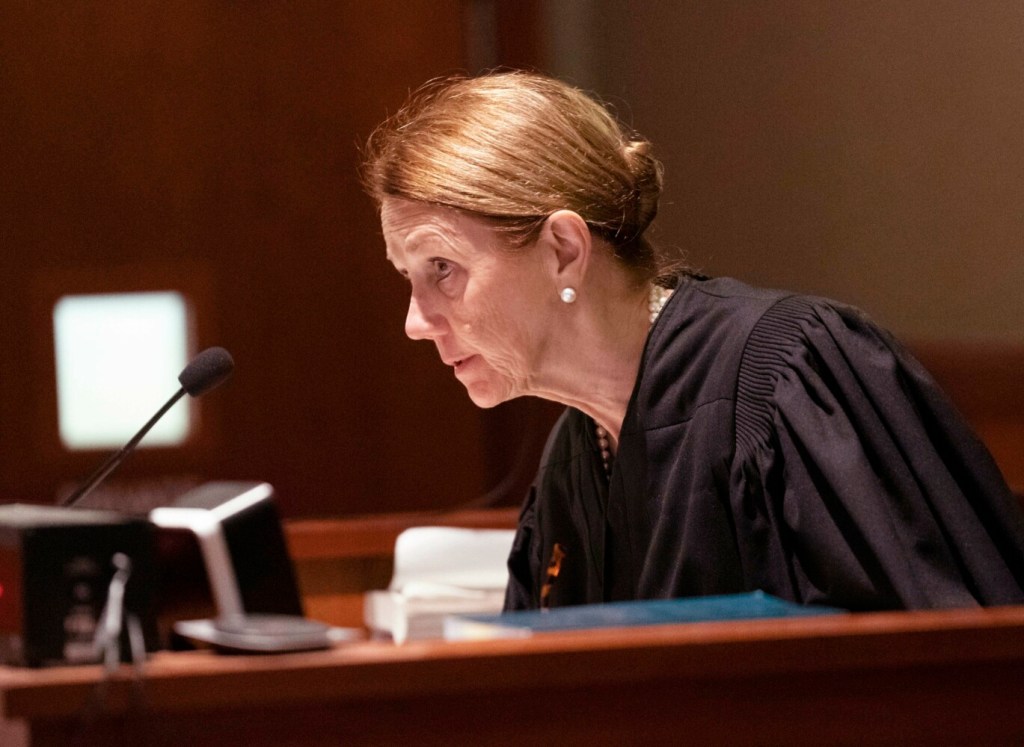

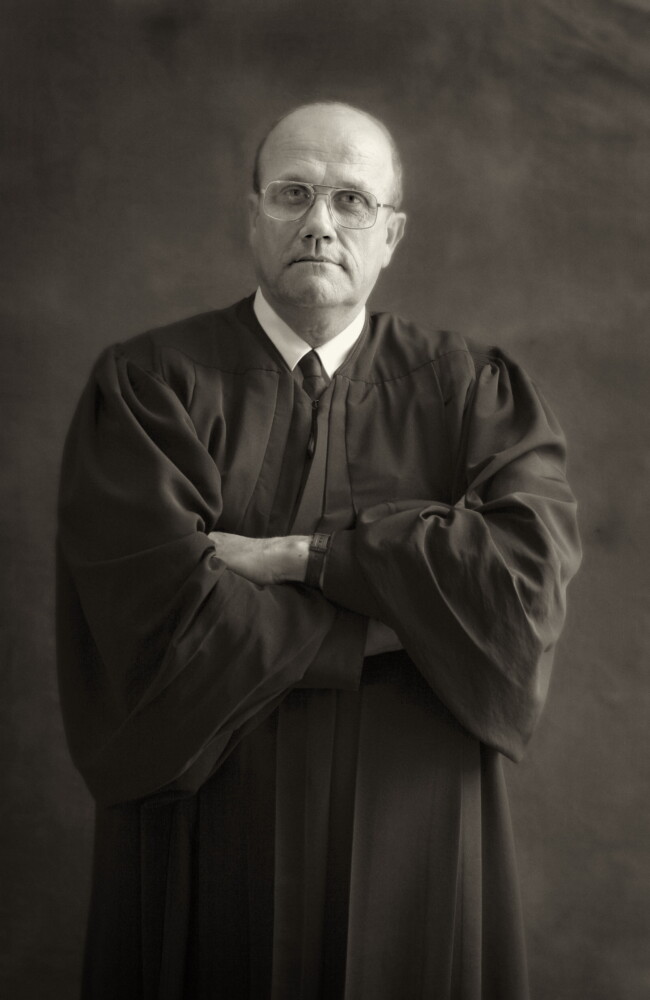

Justice Roland Cole was first appointed to the Maine District Court in 1981 and the Maine Superior Court in 1986. Justice Nancy Mills first joined the District Court in 1991 and the Superior Court in 1993. Both graduated from the University of Maine School of Law and held the role of chief justice in the Superior Court at some point. Their shared retirement date was Dec. 31.

The two judges oversaw high-profile cases that made headlines in Maine. But they also served as the incarcerated population increased both nationally and in Maine, and they founded alternative tracks in the court system that are meant to divert vulnerable people from jails and prisons. Enrollment in those programs has increased steadily as the opioid crisis has taken its toll on Maine, and more than 260 people participated in all of the state’s treatment courts in 2018, the most recent year for which data was available.

“It is hard to imagine the Superior Court without those two justices,” said Deirdre Smith, the director of the Cumberland County Legal Aid Clinic at the University of Maine School of Law. “They’ve done so much individually to really transform the modern Superior Court and the modern courts generally.”

“They’re both real leaders in the judiciary,” she added.

While the two justices had distinct styles on the bench, prosecutors and defense attorneys alike said they are both known for fairness.

“The two words that everyone would use to describe both justices, even though they’re very different personalities, they’re both incredibly tough but also ultimately fair,” defense attorney Tina Heather Nadeau said. “I don’t think the defense bar or criminal defendants necessarily think that of all judges.”

MAINE’S FIRST DRUG COURT

Twenty years ago, Cole noticed a trend.

He had already been a judge for nearly two decades, and he told the Portland Press Herald in an interview at the time that he was sentencing the grandchildren of people he sent to prison years earlier. He attributed those cases to a generational pattern of drug and alcohol abuse, so when the top prosecutor in Cumberland County got a federal grant to start the state’s first drug court in 1998, Cole joined that effort.

“If we don’t deal with this group of young people, they are going to die,” Cole told the newspaper in 2003. “I think that would be a tragedy.”

Now, adult drug treatment courts operate in five counties in Maine — Washington, Androscoggin, York, Hancock and Cumberland. The judicial branch has also established a family treatment drug court for child protective cases that involve parental substance use, and those programs run in three counties — Kennebec, Androscoggin and Penobscot. Maine’s drug court only accepts people who have entered a plea agreement to a crime, which is not the case in all states. Participants engage in treatment and meet regularly to talk about their progress with a team, including a judge. Successful completion can reduce the person’s ultimate sentence.

Data on treatment courts is lacking in Maine, and many questions about their effectiveness are unanswered. But the Maine Judicial Branch points to a 2016 study that indicated that only 16 percent of people who graduated from the adult drug treatment courts had a new criminal conviction within 18 months of admission. By comparison, people who were admitted and expelled had a 49 percent recidivism rate.

“When those courts started, that was a completely radical idea, that you could come out of a court process better, with some improvement in your life and not just having been judged, literally judged,” Smith said. “That really required for all of us to think very differently about the role of courts and the role of judges.”

Cole oversaw major criminal matters during his tenure, including the recent case of James Talbot, a former Catholic priest and longtime teacher at Cheverus High School. On the day jury selection was scheduled to begin in 2018, Talbot instead pleaded guilty to charges that he sexually assaulted a boy in Freeport in the 1990s. Cole ordered Talbot to serve 10 years in prison, with all but three years suspended.

That day, Cole said that he took the unusual step of meeting with the lawyers to talk about the potential difficulties of jury selection. That decision reflects the reputation Cole has built as a mediator, and attorneys said they hope he is still available for that role in his retirement.

“Justice Cole has always been very talented to get parties to come together for an agreement on a sentence,” Cumberland County District Attorney Jonathan Sahrbeck said. “He’s very good at pointing out deficiencies in a prosecutor’s case or the reasonableness of an offer that prosecutors are making and that defendants should consider.”

A FOCUS ON MENTAL HEALTH

Twice a month, Mills convened what she calls “the Languishing Committee.”

“Somebody said, we really need to change the name of this committee, and I said, no we don’t,” the judge said in an interview last month. “That’s exactly the point of this committee, to make sure that people with mental illnesses are not languishing in jail.”

Mills has developed a particular interest in mental health issues during her tenure.

In 1990, another judge approved a consent decree that settled a lawsuit filed by patients at the Augusta Mental Health Institute, and the agreement was meant to make dramatic improvements in the Maine’s mental health system. In her first years as a judge, Mills became involved in the case and decided legal disputes about whether the state is meeting its obligations. In 2004, Mills wrote in a 354-page decision that state officials had failed to meet the terms of the consent decree and should have acknowledged their failure.

“This is not a failure of funding,” she wrote. “This is a failure of management to get the job done.”

The following year, Mills started the state’s first Co-Occurring Disorders Court in Kennebec County. The program accepts defendants who are facing prison time for serious crimes tied to mental illness and substance use. Like the drug court, this track is designed to avoid incarceration and help participants get treatment for their underlying needs. Data about this court is also limited, but the state has said the rearrest rate of graduates is lower than that for people who go through the traditional process.

Mills has also opened a veterans track of that court, and she has overseen the adult drug treatment courts as well. While the Co-Occurring Disorders Court only has one location, in Augusta, she established a docket in 2018 in Cumberland County for cases involving severe mental health issues, especially when defendants are psychotic and not competent to stand trial. At the request of the sheriff’s office, she also started the Languishing Committee to discuss delays in those cases and move them forward more quickly, and its membership represents a wide range of positions in the criminal justice system.

On Friday, Mills testified at a public hearing in Augusta on a bill related to community services for people with mental illness, and she gave an example about a recent case that came to the committee’s attention in November. A man with dementia was lying naked in his cell in the Cumberland County Jail. He was not competent to stand trial, but he did not have another court appearance scheduled for three months. Members of the committee quickly contacted the judge and the attorneys to expedite the case, and the state found an appropriate placement for the man. The charges were dismissed.

“We are trying very hard, but the criminal justice system is not designed to be and does not want to be the default service provider for mentally ill people,” Mills said. “The jails should not be the safety net. Services from qualified departments and agencies should be the safety net.”

Defense attorney Sarah Branch is a member of that committee and often represents defendants who have severe mental illnesses.

“I don’t accept the status quo because each one of these cases is worth the fight,” Branch said. “It is not acceptable that we have allowed the jail to be the replacement for what would be a more appropriate treatment facility. And to have a judge be willing to hear my arguments, I’m not saying I win, but she’s made herself available. … She makes me work harder.”

Both prosecutors and defense attorneys said Mills holds every person in her courtroom to a high standard of preparedness – and punctuality. Years ago, defense attorney Walt McKee was rushing to get his kids ready for school in the morning.

“I said, I’ve got to be in court this morning, I can’t be late,” McKee said. “My daughter, who was 6 years old at the time, she said, ‘Is Justice Mills in court this morning?'”

“People who start working with her in her court, they often have the view that she is a particularly stern taskmaster,” the attorney added. “And to a certain extent, she is. She demanded lawyers do the best work and be on time and be squared away. But there was a side to her, once you got to know her and practiced more in front of her, she was an incredibly compassionate person who really had a strong sense of the importance of doing justice.”

‘READY WHEN YOU ARE’

Gov. Janet Mills has nominated the two judges to active retired status, so they could still take cases or work part time. She has also chosen people to fill their full-time positions. Those nominations are reviewed by the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee and confirmed by the Maine Senate. (Nancy Mills is married to the governor’s brother, Peter Mills, executive director of the Maine Turnpike Authority and a former state senator.)

Last year, Maine Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Leigh Saufley used her annual State of the Judiciary address to say that the state could not grow the treatment courts because Maine lacks the community resources to support people with addiction and mental health needs. Instead, she asked the Maine Legislature to fund services like medical and mental health care, addiction recovery programs, safe and sober housing, data collection and job training opportunities.

“What is needed to expand those dockets is a comprehensive community plan,” Saufley said.

“The bottom line is: The Judicial Branch has a protocol in place that allows the creation of new addiction and mental health dockets as soon as the key components are in place in your communities, and you need not focus that funding on the Judicial Branch,” she wrote. “We are ready when you are.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.