Biennial juried exhibit

displays artwork of 93

LEWISTON — Once again, USM-LAC’s Atrium Art Gallery curator Robyn Holman has assembled the work of many decidedly more-than-accomplished area artists into another beautiful and brilliant exhibition.

Over the past few years I’ve probably reviewed most of the art shows put on here, many of them also featuring the work of Maine artists, and all have been considerably more than a bit beyond “wonderful.” Many of the works shown have in fact been worthy of this country’s more famous big-city galleries and museums—MOMA, say, or the Smithsonian. But the day I walked in here to start taking notes for a review of this show, I immediately felt something even deeper than my usual reactions to Atrium’s exhibits, as though the colors surrounding me were somehow even deeper and brighter, the images more wondrous than I’d felt here in the past. I was aware of the almost unbelievable intensity here—the work of 93 accomplished artists from a mere three counties in central Maine—not a possibility that would probably ever even occur to any of the curators of those big-city galleries.

Any of the visitors to previous shows here—and they are many—are already well aware of the depth and breadth of Maine art—and the ongoing revelation of formerly-unknown artists rising into recognition. Here we have it all—depth, breadth, and artists both known and unknown.

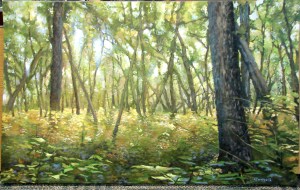

The first painting you’ll see as you come in through the main entrance will immediately take you into a different season; directly in front of you, you’ll step out of this cold winter into the edge of early fall—last fall—next fall—any Maine autumn you’ll ever experience—“Raven’s Grove,” Ryan Connell Garvey’s beautiful, wild, slightly-abstract large canvas opening your eye into an open woodland glade of slender leaning trees, sunlight falling through them from a somewhat cloudy sky to light up a great spread of waist-high undergrowth, its gentle brilliance seeming to illuminate the woods from below as much as its source does from the sky. A painting that in its own way opens you to many of the rest of the wonders in this exhibit. Nature is a major—but certainly not the only theme here. And the abstraction noted above takes its way through into much of the work on display—especially in its play through most of the otherwise “realistic” work. And it works—wonderfully and beautifully. “Raven’s Grove” carries that effect. You enter the door and know you’re looking at a painting of a forested landscape. Not an ideal or magnificent landscape, but an ordinary woods; the trees so slender they could be coming up through a local logged-over lot like the one down the road from your grandfather’s place. You come closer and notice that the bark on the trees is not realistic —you can see a certain ‘shagginess’ brought out by the brush. Nor is that undergrowth given realistic detail; it’s not blurred, but it’s not real, the light on it is somehow too bright. It’s odd. But all this subtle unreality somehow pulls you in, re-adjusts your thinking, makes you wonder, makes this unreality somehow more real, intensifies your attention, your thoughts on reality itself ….

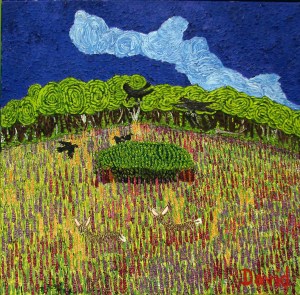

Nearby, near the top of the left-hand gently sloping walkway that takes you down to the main gallery floor, is a more intense version of that abstraction—David Dupree’s “Deer and Lupine” oil on canvas impasto painting, the paint thick over the entire surface, almost seeming to form its own atmosphere over every object in view, individualizing the surface of everything in sight. The picture large, square, as though looking outward from a distance over a field of lupine where two small deer, ears alert, staring your way. Behind them is a small copse of brush with four crows, three of them already landed on it, the fourth about to set down. The field is large, filled with long, tall, stalks of lupine—hundreds of them—each stalk standing on its own, its flowers standing out pointillistically from its stem. Hours and hours must have gone into their creation. Paint swirls thickly out from the copse of brush, even more thickly from the curly-topped impasto woods lining the horizon. The deep, dark sky above it all a thick mix of blues. The long cloud standing out from it seems almost like a living creature. Imagery inviting you to explore it in every detail.

Further down the walkway Sheila Patrick’s oil-on-canvas “In the Beginning” stands out from its wall even from a distance—an abstract cosmic swirl of varying blues, yellows, greens, reds and black — with stars of all sizes — from huge to pinpoint —rising in and around it.

Next to Patrick’s cosmos hangs another piece questioning of time and meaning—Thomas Neubert’s “On the Origin of Species”—collage, acrylic, found objects. Even its frame is a collage forming part of the question—clam and nautilus shells growing out from it along with other objects, including what seems to be a jaw of blackened teeth and a sprung mousetrap clasping a twisted, metal spring. Inside the frame more collage—fingers coming in from its edge holding a cover of “The Origin of Species,” dand crawling down the other imagery a pair of very realistic lizards stand out from the surface, one large the other small, on their way down toward that already-mentioned mousetrap.

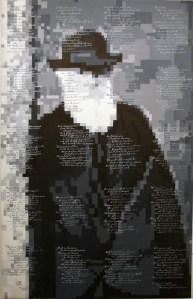

On a nearby wall, Nuebert has another—much larger—work, “Darwin on Fire”. Seen from a distance it looks like a portrait of a nineteenth-century man, all done in dull blues, greys, black and white. White hair and beard, black hat with a rounded crown and narrow brim. As you come closer the imagery begins to break apart—the closer you come the portrait breaks up to dissolve into little squares, and when you stand directly in front of it you see that the little squares are pixels—the kind of little squares you’ve seen on your TV screen when its image begins to break apart. When you’ve come this close you can see that this is how Neubert has formed Darwin’s portrait—dozens of pixels, each its own shade from the dull colors listed above—a Darwin formed in almost futuristic fragments. And standing there now, you can see that the artist has handwritten 20 quotes from Darwin’s writings—some scientifically philosophical, others personal, all broken into poetic lines. The artist here is trying to tell you something. He wants you to think about it, and you can’t help but to be drawn in.

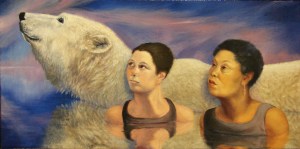

Not far down the hall from “Darwin on Fire,’’ you’ll see Sandra Stanton’s “Arctos”. Two women stand head and shoulders above the surface of an ocean, a peaceful polar bear in profile immediately behind them. All three are looking upward toward the right-hand corner. We cannot see what they see. Their expressions are serious, wondering, but not fearful. Elsewhere, Stanton has another painting, “Array.” This time a single woman, blonde, same pose, same circumstances. Sky and water reflecting each other in various tones of blue, grey andwhite. A few small birds behind her seem to be about to land on her shoulder. One has dived into the water, its tail rising from the surface.

There are nearly a hundred paintings here. All are interesting, all carry their own aesthetic, their own meanings. My space here is limited. Obviously, I can’t get to them all. I do need, though, in fairness, to get to some of the other media. And among the other media is one I’ve not only never seen before; I never dreamed it even existed. “Temporary sculpture” I might call it, or “see-through sculpture.” Megan Hulbert’s female figures are made from packing tape; that ordinary plain plastic material used to wrap all kinds of items in transit. Two of these figures are standing and a third is sitting, on a little platform under the stairway. They have been shaped, a little at a time, from living models — arms, legs, torsos, wrapped in the tape then removed and fitted together. Obviously life-sized, realistically shaped, and with no seams showing, their insides simply air.

To actually even see them is a remarkable experience. You could be looking at ghosts, spirits. Indeed, the exhibit is titled “From the Room of Hungry Ghosts,” and Hulbert took the idea from a Buddhist concept, one of the ‘six realms of existence’ in which the souls of some people have been emptied through their manner of living, and in this case the artist is referring to those entrapped in addiction.

Other abstract 3-D works here would include Karen Campbell’s 18-inch high aluminum wire “Cowboy Boot,” crafted not only to the accurate shape of its subject, but covered as well with the kind of images and designs that go onto the typicality of that realm of footwear.

Not far from Campbell’s “Boot,” you’ll probably see small groups of people ever gathering around a glass case containing JR Pelletier’s very complex constructions of two small four-wheeled vehicles, one named “Lefty Lefty,” the other “Ted’s Tuna Hauler.” Almost all of the parts here are tiny and number in the hundreds. I’ve seen Pelletier’s seven-page, large-type list of the 183 pieces that make up “Lefty” alone — its main body, the largest, is a 30-inch block plane, 10 inches high and 17 inches wide. Among its other parts are an acorn, meat-grinder blade, a small red apple, gold watch chain, two film reels, eight red necklace beads, two wine goblets, a green snail, salad tongs, earrings, forks, spoons, a napkin holder for its grill, one candle holder for a headlight and another for its exhaust. More parts in its 30 inches than the 112 works in various media that make up this entire exhibit.

There is so much excellent work in this show that many visitors, myself included, have come back again—more than once. In fact, re-visits are almost required. If you haven’t come in yet, think about that and give yourself plenty of time to get in at least one repeat visit before April 4th.

Comments are no longer available on this story