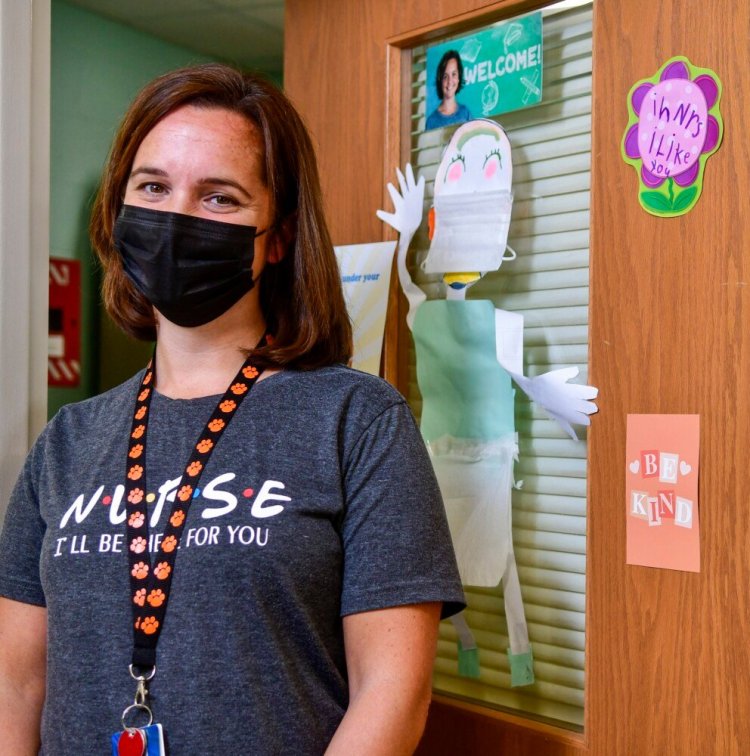

“We just want them to hear the message,” said registered nurse Melanie Lecours. “It hurts.”

Lecours is the nurse team leader for Waterville Public Schools.

She and other nurses across the state have reported crude and “angry” behavior from parents directed toward them when calling to deliver COVID-related information. The responses from parents have gotten so bad that administrators have had to step in to remind families how to treat the nurses.

“I’ve gotten really criticizing responses,” Lecours said. “Saying we don’t know what we are doing, that their child ‘couldn’t have been exposed,’ saying we are ‘incompetent,’ ‘idiots,’ that we are doing this based on ‘political agenda’ and it’s been hard to hear.”

Superintendent Pat Hopkins from Gardiner-based Maine School Administrative District 11 sent a letter out to families last week and made note of some interactions her nursing staff reported with parents. Hopkins not only reminded parents and caregivers of the amount of work the nurses have to do, but that nurses are “just doing their jobs.”

Cathy Jacobs, who chairs the Regional School Unit 38 school board, had to take a similar approach to the district and told families to treat the nurses “with kindness and respect.”

Lecours estimates around 20% of her calls are met with anger and with the Waterville Public Schools encountering more COVID-19 cases in the month of September than all last year, she has had to make a lot of phone calls.

She and her team have done a “good job” making the calls, she said, but now, most of her staff has “fear” over making the phone call to parents.

“It’s painful, and it really hurts, that’s all I can say,” she said. “I get off the phone and have to gather myself and call another parent where I have to have the same gentle approach to the conversation.”

Per rules from the CDC, it’s recommended school nurses make direct contact with a parent or guardian, but since the nurses have gotten so “verbally abused,” the Waterville Public Schools have started doing robocalls and following up with emails. Lecours said as a standard practice, they always follow up with an email with more information because the thought is that the initial call “might not be heard,” especially if it’s met with anger.

“Because it’s been so verbal and because we have been so verbally abused, we have done robocalls where the call is automated to decrease the aggression to nurses,” Lecours said. “It’s something I think more districts are doing.”

And now, more than ever, nurses are dedicating most of their time at school to handling COVID-19 cases.

Alaechia Ellis, a nurse at Cony Middle and High School in Augusta, said around 80% of her time is dedicated to COVID-19 and the rest is spent on “normal” high school nurse duties, like handing out bandages or checking headaches. The Augusta Public Schools are participating in pool testing, too.

Like Ellis, nurses across the state have had to spend more time after school and on weekends calling parents about close-contacts and possible COVID-19 cases. Part of that process requires determining who students may have been in close proximity to during the previous two days.

At the high school, Ellis said she hasn’t experienced too many upset parents, but reminds families that nurses “are all trying to do our best” and that the nurses also have rules and guidelines for COVID-19 they have to follow, as does everyone else.

Through her network of nurses, Lecours said she has heard similar stories across the state and though most students are no longer in a hybrid schedule and are back in person full time, the virus is still present.

“I think they (parents) are frustrated because they had students home so much last year, and with that, they want to go back to work and back to life and go about a normal day, it feels like the world is turning normal,” she said. “Then schools come in to play. You’re not usually getting a call about being quarantined (when outside of school).”

Kristin Martin, the lead nurse at MSAD 11, would agree.

She tried to explain the reaction from parents as a “misdirected anger, or frustration.”

“Parents have to work and they think they are being punished for doing the right thing,” Martin said.

Ellis agrees that parents she calls are likely frustrated about missing work, but said there is “not one thing” that she can pinpoint for their frustration.

The school districts have done their best with interpreting the CDC guidelines, which can vary from what safety measures school boards have decided to adapt. For nurses, admittedly the directives can be “confusing” and “frustrating” to follow.

Specifically, the rule about where a child comes into contact with COVID-19 — if they are a close contact at school, they can continue going to school, but if they are a close contact outside of school, they have to stay home.

“I understand some of the CDC guidelines are questionable, but we are the messengers,” Martin said, adding that part of training for nurses is how to deliver sensitive material. “But it’s one thing to express frustration with a rule and try to understand why a rule has been in place, but unfortunately, it has turned pretty bad.”

Martin said she understands both sides of the argument and tries to listen to families or concerned parents when she delivers the news that their child might have been in close contact with a positive COVID-19 case. And as a nurse, she has seen students come to her daily with headaches and stomachaches and other things that could be caused by wearing a mask six hours a day.

“I try to say, I hear you, I am a messenger telling you the justification, from the superintendent, from the CDC, I hear you and I see all angles,” she said. “I have two kids in the system and sometimes it’s frustrating for me, but we all have to do our rules and follow our part so we can get out of it quick.”

Since Superintendent Hopkins put the letter out to MSAD 11 communities about a week ago, Martin said people have called her apologizing and have, overall, been nicer on the phone.

Lecours said for her in the Waterville Public Schools, they have tried to contact the Maine Department of Education and CDC about the situation, hoping there is something that can be done.

But the message Martin said she wants to leave for families is that nurses are “always on the children’s side.”

“We are all on the same team,” she said. “We are not working against families, we are trying to help and all we want to do is look after the health and safety. We aren’t the enemies, we are trying to help.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story