On a weekly basis, it seems there’s a new sculpture, a new mural, or a new temporary art installation going in here or being dedicated there. It’s happening all around Portland and across Maine in smaller communities, like Bethel and Yarmouth.

Public art used to be a conundrum. Now it’s almost routine. As we move toward a post-pandemic world, public art represents one way of bringing people back together again, of creating new and safe outdoor spaces for human interaction and a chance to go big – while also changing the color scheme of small-town New England.

“The appetite for public art has really grown,” said artist Wade Kavanaugh, who co-owns the Gem Theater in Bethel, which Portland painter Ryan Adams has turned into a 360-degree, 9,000-square-foot mural with more than two dozen colors, all paid for by the community and with grants. “People are always asking, ‘Have you thought about this wall? What about that wall?’ People are making it a part of their ordinary life, which is great.”

In the past, public art projects were often delayed and derailed by layers of committees and a vetting process that stripped artists of autonomy and vision and also often left the public feeling like it had no voice. Kavanaugh, who often works in the public arena, called that process “death by committee. By the time they get made, they are so beige they don’t contribute to the vitality of the space they are meant to enliven.” As problem-solvers, artists have learned to move around those roadblocks by working directly with funders or on projects that are paid for privately and with public-private partnerships. And sometimes, they still work with public art committees.

Examples of all abound.

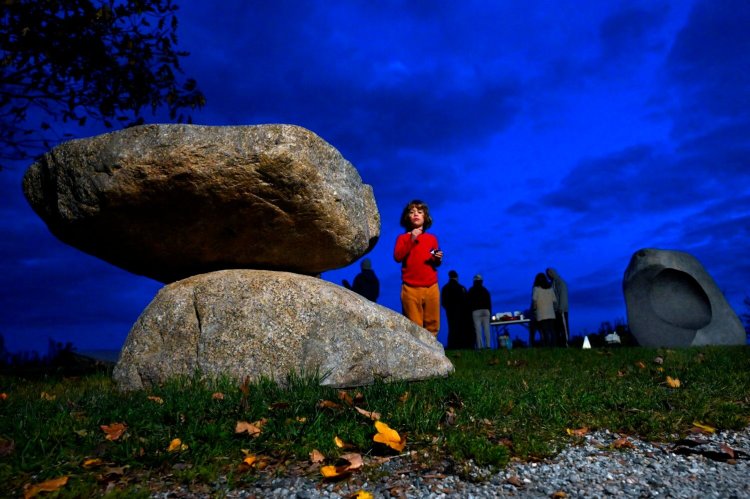

Last week, TempoArt, a privately funded Portland nonprofit that promotes public art though temporary installations, held what it described as a closing ceremony for “Gathering Stones,” a temporary sculpture by Steuben artist Jesse Salisbury that has been part of the landscape of Fish Point by the Eastern Promenade since July 2020. But the sculpture – an array of shaped boulders of granite and basalt – has become a gathering place for human interaction, and may not be going away. The city granted a one-year extension to the temporary-art permit over the summer, and now the Portland Public Art Committee is trying to flip its status from temporary to permanent by adding it to the collection of city-owned art.

The committee has proposed spending $32,000 of its fiscal 2022 budget toward the public purchase of “Gathering Stones,” or about half the expected cost of the sculpture. The rest would be raised through private fundraising coordinated by Creative Portland.

“It’s not going away. People love it too much,” said Julia Kirby, who has served as a volunteer on the citizen public art committee for nine years, including several years as chair and vice chair. “It is right in plain sight, but you don’t notice it right away. Dogs jump on it, people sit on it, people stand and look at it. People love to take their picture by it.”

Sculptor Mark Pettegrow, right and metalsmith Ray Mathis install panels in October below Pettegrow’s bronze sculpture titled “Passing the Torch,” which is located in the center of Portland’s first roundabout at the intersection of Brighton and Deering avenues and Falmouth Street. Gregory A. Rec/Staff Photographer

At 3:30 p.m. Monday, the public art committee will cut the ribbon on the installation “Passing the Torch” by artist Mark Pettegrow at the new Deering’s Corner Roundabout, near the University of Southern Maine at the intersection of Brighton and Deering avenues and Falmouth Street. The piece, which the committee commissioned in 2019 and with a budget of $123,000, includes three bronze flames that are between 8 and 12 feet tall rising from boulders of Maine granite atop the roundabout.

Around the corner from the roundabout, on Forest Avenue, painter Patrick Corrigan has been taking advantage of favorable fall weather to continue his work on a massive 170-foot mural on an Oakhurst Dairy wall depicting iconic local scenes, including Portland Head Light and the Portland Observatory, as well as grazing cows, sunny sailboats and majestic mountains. Paid for by Oakhurst in celebration of its centennial, the mural is a private investment in a piece of art that is very much in public view – like the Charlie Hewitt “Hopeful” sculpture atop Speedwell Projects just down the street.

Painter Pat Corrigan, right, and assistant John Supinski work on a mural commissioned by Oakhurst Dairy at its Forest Avenue location to show appreciation for the community, Maine dairy farmers and Oakhurst employees. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

Oakhurst president John Bennett wouldn’t say how much money the company is spending on the mural, and described it as a “sign of our appreciation for being able to work in this area and the wonderful employees and families who have contributed to our success over the years. We had a nice logo up there, and that was good. This was an opportunity to do something for residents and visitors to Portland, as well as employees, our farmers and our customers.”

The mural is “by far the largest thing I have ever done,” said Corrigan, whose handiwork as a muralist can be seen on buildings across the city and inside the recently opened Children’s Museum and Theatre of Maine at Thompson’s Point. “It’s incredible sitting up there with a brush 12 inches away from the wall, and I look to my right and I see how much I have left to do. I feel like I am one of those workers in Egypt building a pyramid. But the view from up there is great.”

GOING BIG

Ryan Adams can relate to Corrigan’s experience. This summer, Adams spent plenty of time high off the ground, transferring the details of his preparatory drawings to the side of the Gem Theater in Bethel. It’s likely the largest piece of public art in Maine, and was commissioned by Bethel Area Arts and Music and paid for through a variety of sources, including grants and donations.

Kavanaugh recruited Adams for the job, first suggesting that he paint a single wall for what would have been a relatively simple mural. Together, they decided to go big and expand from one wall to four and from five colors to more than two dozen. “A public art project on this scale used to be something a big institution would take on, but ours was community-based and community-funded, and that is what is so exciting about this piece. A piece like this should have taken institutional support to pull it off, but we did it with the community,” Kavanaugh said.

The artist Ryan Adams works from a bucket lift on the blue corner of his mural on The Gem Theater in Bethel in June. The mural covers all four exterior walls of the movie theater and transitions through every color of the rainbow. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

Through his art, Adams has transformed the community. Among other things, the project in Bethel represents an era of bold, daring colors. “It’s the end of beige,” Kavanaugh said, again invoking a call for the end to bland. “The assumption in a New England town is if we default from beige, everybody will talk about it. This is about as big a deviation as you can get – and people are talking about it.”

Adams, who began as a graffiti artist and now shows his art in museums, couldn’t resist the challenge. For such a large project and with so much opportunity, he worked with local students to talk about the design, theme and messaging they wanted to see on the building. Working collaboratively, they settled on themes of resilience and togetherness – “We Go Together, We Grow Together” – and Adams led teams of volunteers to complete the project in June and July, working around what was then persistent wet weather.

Adams paints murals in Portland, across Maine and across the country. He likes working large and he likes working outdoors. Painting publicly means he can reach people without having to interact with galleries and museums – though Adams is doing both of those things at this stage of his career. But public art remains a priority.

“My background is graffiti, and I am used to having stuff out there – allegedly,” he said. “The reason I continue to go that route is accessibility (and) having the work out there for anyone to interact with. From my own personal experiences, for a long time and even now, the art world can be distanced and closed off and hard to reach. You would think it would be inclusive to everyone, and it doesn’t feel that way all the time. To have art out in the world so anyone can interact with it is very important to me.”

Among the most accessible recent public art installations is at Rock Row, a commercial development in Westbrook. For the installation “Rock Row: Inside, Outside the Box,” developers paid several local artists $5,000 and $10,000 each to install work in, on and alongside shipping containers that were placed behind the loading dock at Market Basket. On view until the end of November, the temporary art installation has introduced energy, community and a sense of curiosity to a drab and uninspiring location.

“It’s not a great place for art,” said Portland artist Aaron Stephan, who created a 12-foot aluminum tower called “Structures of Revolution” that references the Eiffel Tower, Tatlin’s Tower and the interior structure of the Statue of Liberty. “But people have noticed. A lot of people drive by there.”

He’s still trying to unwrap the riddle that allowed him to install a piece about socialism in a commercial development based in capitalism, and chalks it up to both the times we live in and the subversive potential of public art. It invites conversations and makes people consider and then reconsider their environment, he said. “It’s very weird, a piece about socialism behind the Market Basket loading dock. I proposed it to them and they were like, ‘Yeah, sounds great.’ And I said, ‘Are you sure?'”

Stephan has built his career in the public realm. In Portland, he’s probably best known for “Luminous Arbor,” the abstract light fixture at Woodfords Corner that mimics the tangled intersection. Most recently, he completed a large commission for the Tampa International Airport, called “Paths Rising,” with more than 600 tapered handmade ladders installed in a dome painted in gold leaf.

He hopes the installation makes people think about their final destination.

Stephan made all the ladders himself during the pandemic at his Cassidy Point studio. It was among the most ambitious projects he’s completed, with a budget of $440,000. He likes the challenge, scale and sometimes even the drama of public art. He’s good at dealing with architects and engineers, and is patient with the public-review process. He’s also an exceptional fabricator and is comfortable working with a variety of materials. With Tampa wrapped up and the subversive tower in Westbrook still standing, he is finalizing a glass-themed idea he will present next week in Toledo, Ohio, for the Glass City Convention Center.

TOURING THE TOWN

The Yarmouth Arts Alliance recently placed a granite sculpture, “Cloaked Figure,” by Roy Patterson at the Main Street Bridge near Merrill Memorial Library. It’s the second sculpture by Patterson the alliance has placed in recent years, and both represent the beginning of what Linda Horstmann, co-chair of the alliance and the town’s public art committee, hopes will be a multistop sculpture trail. The alliance has a third piece in mind and is applying for grants. If things work out, it will be added in 2022, Horstmann said.

The alliance also intends to ask the Town Council to be appointed as the authority for public art in Yarmouth, giving it oversight to build the collection.

“I think we all realize the benefit of public art in a community,” Horstmann said. “It draws people to the community and is good for the economy. Our goal eventually is to have a map of all the public art in Yarmouth that you can access on your phone with information about each piece.”

Back in Portland, the team at Creative Portland is working on an app that will allow people to take self-guided walking tours of public art and murals in the city. It should be ready by the spring, and is among many initiatives the arts agency has undertaken to promote and improve the city’s public art profile. During the pandemic, Creative Portland hired artists to create public-safety messages and to beautify barriers used for street closures.

Artist Justin Levesque, 34, a Maine native and University of Southern Maine graduate, installs “Glacier Retreat” in a Portland bus shelters in 2020. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

Creative Portland also is preparing another round of grants for artists to design bus shelters in Portland, working in tandem with other agencies on a continuing project that makes use of federal funds and local cooperation.

Dinah Minot, executive director at Creative Portland, senses positive energy around public art and a chance to get things done. “What has changed is that people are seeing different styles, different flavors and different artists making the work,” she said. “We have a lot of emerging artists here, who are ready to burst out.”

Jess Lauren Lipton, who chairs the Portland Public Art Committee that is trying to purchase “Gathering Stones” as a permanent installation at Fish Point, agreed with Minot’s assessment that positive energy, cooperation and new ideas are making it easier to get things done.

“‘Gathering Stones’ is a great example of what public art can do for a community and the collaboration between public and private entities for the public good,” she wrote in an email. ” ‘Gathering Stones’ was a Tempo project installed during a pandemic that aimed to connect a community. The power of the piece is exemplified by the fact that within its first year multiple groups saw the value in this work and sought to acquire it for the public collection. We are still in the initial phases of that goal with all parties determined to make it a reality.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story