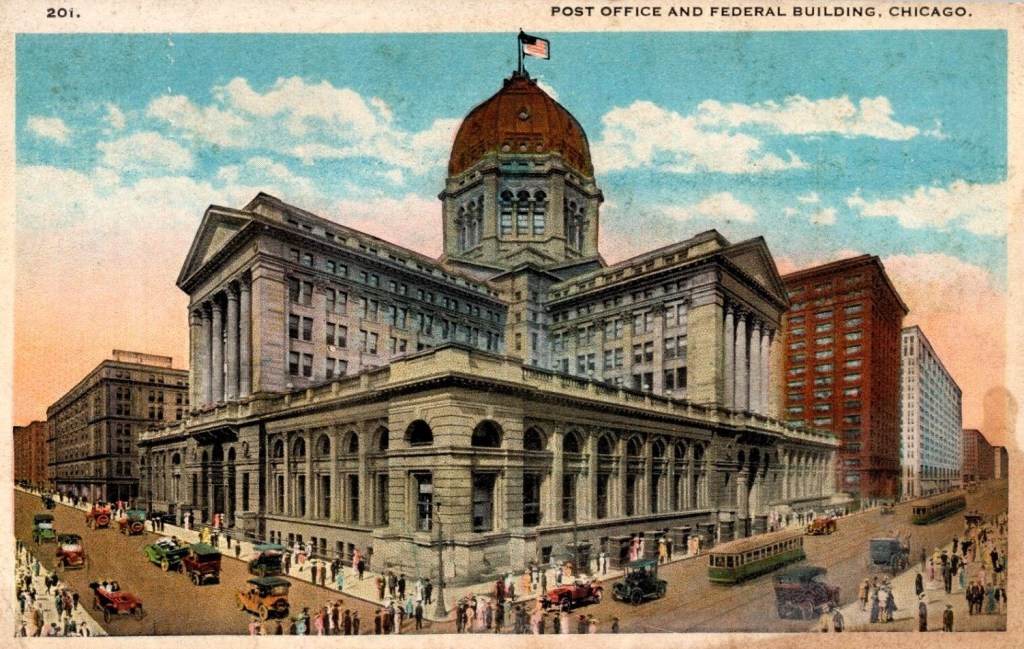

PARIS — After the 1965 demolition of the Federal Building in Chicago, nearly everyone assumed that historic and much-admired murals that hung on its courtroom walls lay amidst the rubble, one more victim of urban renewal’s rush to raze the nation’s past.

The Chicago Tribune noted that “perhaps the most beautiful and most to be missed” part of a leveled courthouse would be the murals telling “the history of justice dating back to the foundations of law in Rome and England.”

Those lush but muted murals lined the walls for thousands of trials over the years, including memorable ones that sent gangster Al Capone to prison and cracked down on the fixers of the 1919 World Series.

All the murals, painted on canvas and glued to the walls, vanished over a half century ago.

A large mural that once hung in the Federal Building in Chicago now belongs to antiques dealer Rich Hagen of South Paris. More murals by William Brantley Van Ingen are rolled up along the sides of the mural on display Feb. 8 in Hagen’s studio. Daryn Slover/Sun Journal

But it turns out at least portions of those murals survived and are now in the hands of an antiques dealer in tiny South Paris.

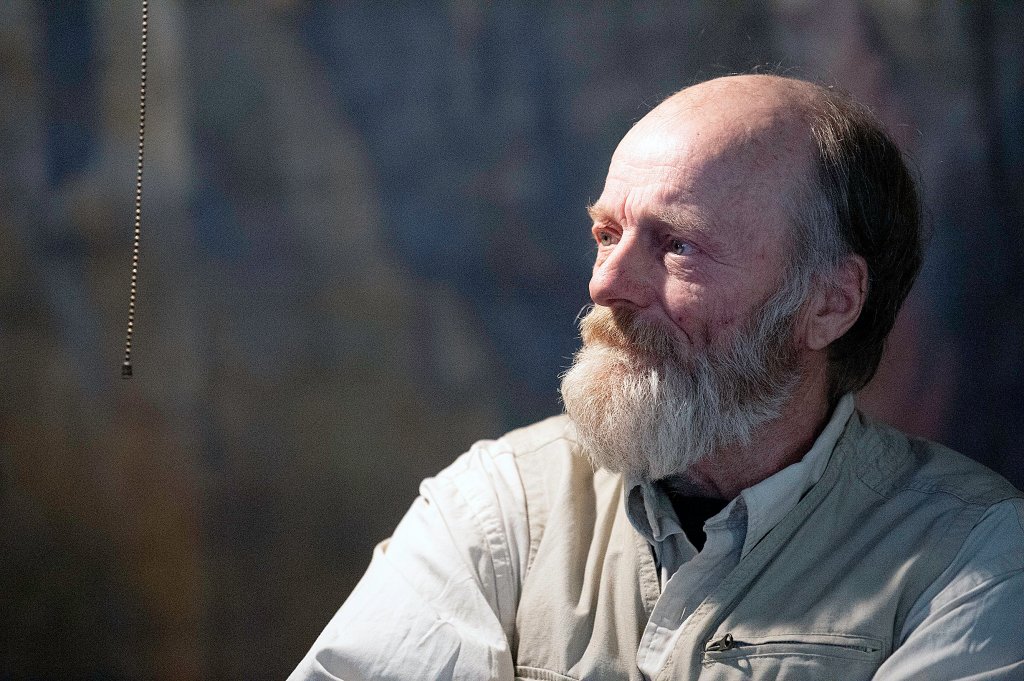

“Most of the murals are in Maine,” said Rich Hagan, an artist, restorer and dealer with a little studio in an old house in the Hungry Hollow section of town. “I ended up with them.”

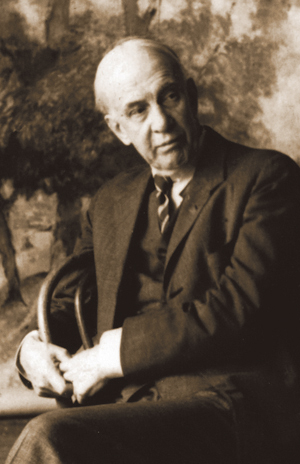

Painted by William Brantley Van Ingen, a much-praised artist in the early 1900s, the large murals graced the walls of four federal courtrooms. He got $45,000 from the government to paint 2,400-square-feet of canvas to fill four courtrooms with law-related artwork.

Several decades after the courthouse fell to the wrecking ball, according to Hagan, an auctioneer on Cape Cod ran across a batch of murals “wrapped up in a big ball” in Miami, Florida, with water leaking on it and mice everywhere.

The guy bought them from the salvage yard where they’d apparently sat for a long while.

When he returned to Massachusetts with the mysterious murals, Hagan got a chance to look. He unrolled one enough to see two knights riding through a field.

“Wow, that’s nice work,” he remembered thinking. “I’d love to have those.”

Hagan, who was working as an artist on Cape Cod at the time, had no clear idea what he was seeing but figured they might have some value. He took out a home equity loan on a house he inherited and made an offer.

“I never thought I was going to get those murals from him,” Hagan said, but he wound up owning them.

“I was, like, dancing when he gave them to me,” Hagan said.

That was about 16 years ago.

He said he wound up with about half the murals, mostly ones related to King John and the Magna Carta, an iconic document that helped establish the bedrock idea that even monarchs were beholden to the law.

They were on Cape Cod until he had to sell his home there. He looked around for a new locale before buying the old house with a tall ceiling in South Paris five years ago, where he’s been ever since.

Hagan poked around for a while before establishing that the murals came from the old courthouse in Chicago. He found photographs of some of his murals on the walls of the historical courtrooms — and evidence that they were always considered something special

The Federal Building in Chicago, which housed four federal courtrooms decorated with historic murals, as it appeared in a postcard issued about 1920. It was knocked down in 1965 and some of the murals wound up with a South Paris antiques dealer.

Both Scribner’s and Harper’s, two of the leading weeklies of the era, lavished praise in 1909 on Van Ingen’s work on the Chicago building.

In Scribner’s in 1909, William Walton said Van Ingen delivered “his great series” on the history of law with murals depicting Moses on Mount Sinai receiving sacred law, King John with the Magna Carta, Socrates discussing justice with friends, Cicero speaking in the Roman Forum and other scenes from history.

Van Ingen — who learned his craft as a student of Thomas Eakins, Louis Comfort Tiffany and other prominent artists — wanted to place “some ancient Greek scholars” in the courtroom of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the painter told the Chicago Tribute in 1921.

He said, though, the well-known judge, who became Major League Baseball’s first commissioner, rejected Socrates for his walls.

Van Ingen said Landis instead “wanted the designs to tell the story of some lawyer known to all the people, so the pictures were painted around the life of Abraham Lincoln.”

Antiques dealer Rich Hagen of South Paris. Daryn Slover/Sun Journal

So Socrates wound up in a different courtroom while Van Ingen’s murals of Lincoln wound up overseeing the action in Landis’ court.

Hagan has some pieces that must have come from the Lincoln murals, including one of the White House and another of a covered wagon departing from Illinois.

“The White House is really cool,” Hagan said, and though it’s not in great shape, he’s convinced he “can probably save most of it.”

He said the best of the lot in his possession is one of King John signing the Magna Carta.

That one, he said, belongs in a courthouse or some other lofty legal setting.

Occupying a prominent spot in Hagan’s studio is one of the Van Ingen murals showing bags of gold being delivered to pay the king of France a colossal ransom for the return of Richard the Lionheart, the imprisoned king of Norman-held England in 1194.

Hagan said he loves working to clean and restore the pieces.

Because the figures are more than life-sized, “it’s like you’re walking right into it when you’re working on one,” he said.

So far, Hagan has sold a handful of them, including two for a house in Bath. He said four of the ones he sold remain in Maine, one is on Cape Cod and the other is in Connecticut.

He’s still looking for buyers for the rest, which he thinks are worth from $3,000 to $8,000 apiece.

U.S. District Court Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ courtroom in Chicago saw many trials that still resonate, from proceedings related to the rigging of a World Series to Al Capone’s bid to remain a free man. Murals by William Brantley Van Ingen can be seen on its wall in this Chicago Daily News photograph preserved by the Chicago History Museum. Chicago Daily News/Chicago History Museum

Though he only had half of them at any point, Hagan thinks some of the others from the old courthouse may survive. He suspects most of the Lincoln-oriented murals were scooped up in Illinois soon after the demolition.

But that remains an uncertainty.

Van Ingen’s murals, painted over the course of decades, remain as treasured artwork in many important buildings across the country — and beyond.

Carroll Berry, a Wiscasset artist, worked closely with Van Ingen after meeting him in Panama while the muralist was making sketches that would lead to his famous murals in the canal zone administration building.

Berry told the Portland Press Herald in 1941 that he helped create the 100-foot picture, a colorful panorama showing the construction of the entire canal.

Van Ingen wrote in Art World that during his work in the canal zone “I forgot I was an artist, and had genuine regret at not being entitled to a number and a brass check” like the workers he met there.

He said any success his paintings of the project achieved “came, I believe, from an endeavor to see with the eyes of the man in the ditch. I was a translator, not an originator.”

A large mural that once hung in the Federal Building in Chicago now belongs to antiques dealer Rich Hagen, seen Feb. 8 at his South Paris home. The murals were by William Brantley Van Ingen. Daryn Slover/Sun Journal

Van Ingen’s work also graces the walls of the U.S. Mint in Washington, the Library of Congress, the Dewey Graduate Library at the University at Albany’s downtown campus in New York, Pennsylvania’s Capitol in Harrisburg, the New Jersey state Senate chambers in Trenton and the federal courthouse in Indianapolis.

Born in Philadelphia in 1858, Van Ingen lived and worked mostly in New York City. He died in Utica, New York, in 1955.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story