More than 100 sugarhouses, farms and maple producers across Maine are preparing for the 41st Maine Maple Sunday Weekend March 23 and 24.

The event falls toward the end of the sap running season and is a boon to sugarhouses across the state as an opportunity to promote maple products and to showcase the process itself. Many sugarhouses have tours of their lines and facilities, breakfasts and events, with some sharing the rich history of Maine’s sweet staple.

Some 41 years of celebrating one of America’s favorite and New England-famous food products is nothing compared to its long history.

Lyle Merrifield, owner of Gorham’s Merrifield Farms and president of the Maine Maple Producers Association, said the practice of boiling maple sap goes back to a time when settlers were still exploring the shores of North America, though collecting the sweet sap goes back much further.

Spouts were once hand carved by farmers using whatever bits of wood they had available. Each farmer’s spouts tended to look unique to their cuttings. These are on display at Merrifield Farm in Gorham. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

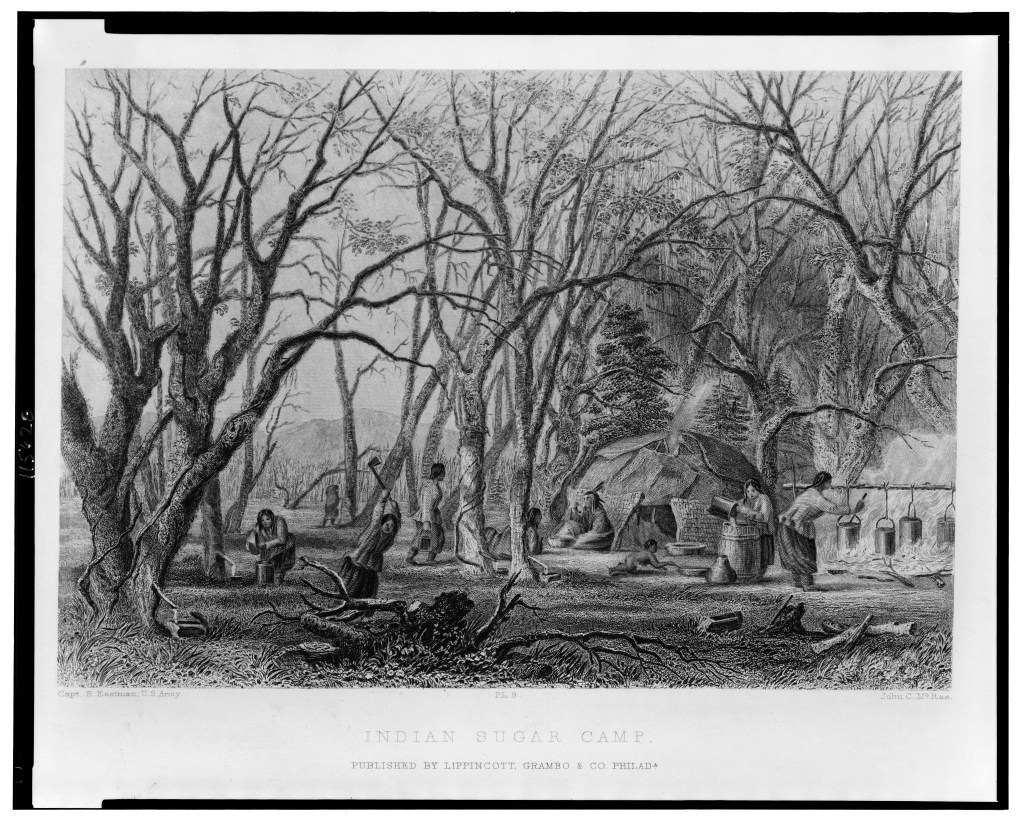

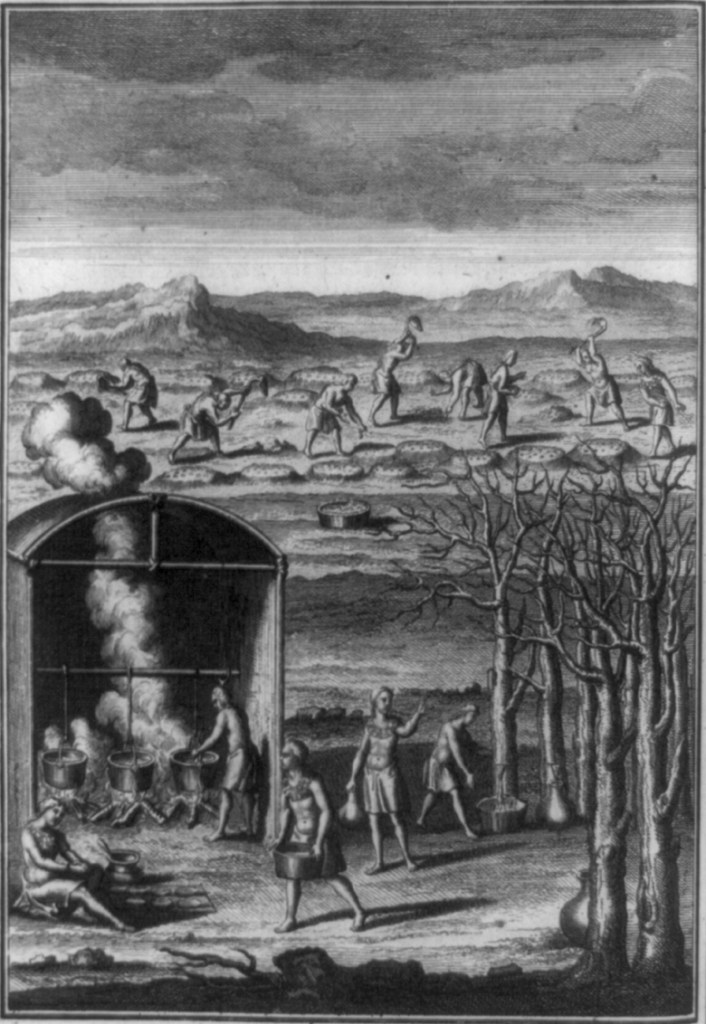

“Native Americans were the first people to start producing syrup, but much of it was halfway there, just a heavy sweet water,” Merrifield said.

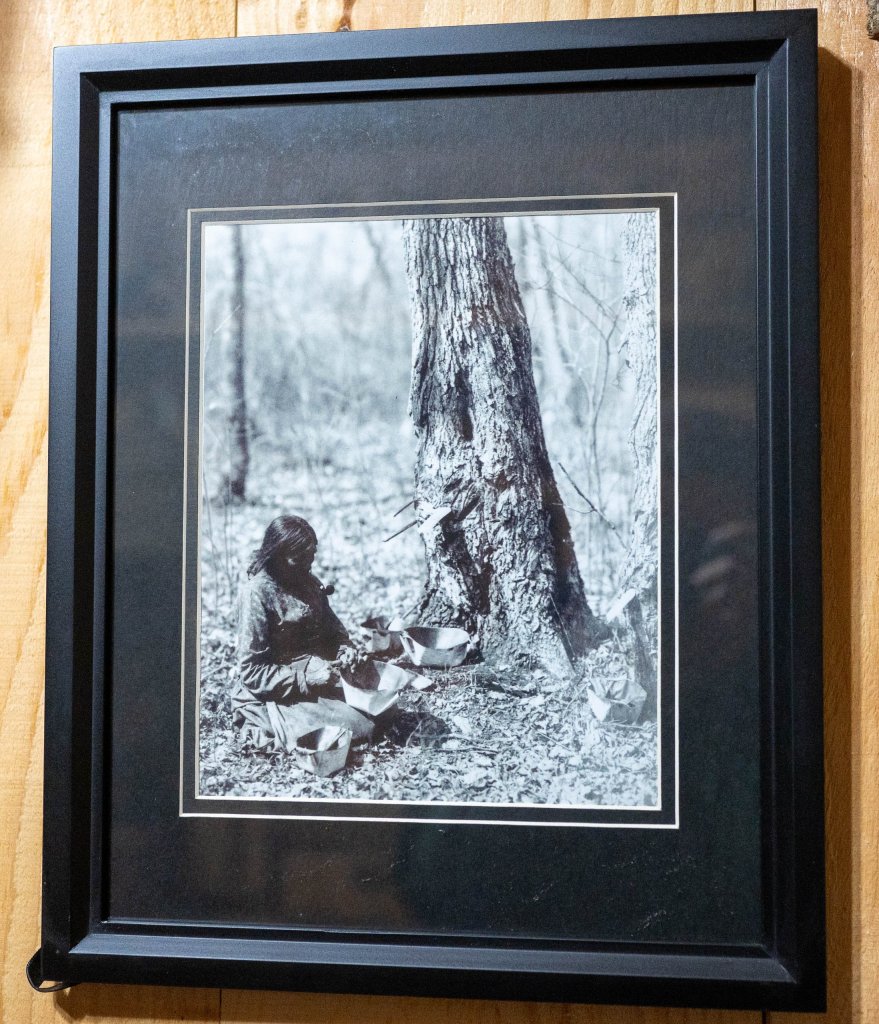

Collecting sap was largely a tradition of the tribes in northeastern North America — where the sugar maple grows — though tribes at the western edges of the sugar maple’s range around the Great Lakes and beyond also practiced sap collection. Tapping methods varied from simple V-notches in a tree to wood spiles, a cone-shaped tube similar to the taps used today. The sap would be collected in baskets or wood or clay bowls set below the taps.

A container of taps used by early Native American sap harvesters is on display at Merrifield Farm in Gorham. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

Once collected, uses varied. In some cases, the thin sap was consumed as is. In some cases, the sap would be poured off into large troughs or birch bark baskets, where it would sit overnight, the sugar would settle to the bottom and the cold liquid would be poured off to access the sugar.

Another common practice was to heat the sap to remove moisture and thicken it. “They’d make the sweet water by putting hot stones into (the) troughs filled with sap,” Merrifield said.

The hot stones would steam some liquid off leaving a slightly thicker and richer sweet water, which would be drunk or used for cooking. The practice dates back as early as 1609, according to several scholarly sources, but it is believed that indigenous tribes tapped sugar maples long before settlers arrived. Some indigenous descendants say oral history puts the practice as far back as a thousand years.

Once settlers introduced copper kettles and cauldrons, indigenous people brought the process even further, producing maple sugar almost exclusively, Merrifield said. Settlers then took up the process. The developing world’s Caribbean sugar cane trade, which began in the early 1500s, was at that time serving mostly upper-class European societies. Since sugar cane and beet sugar was prohibitively expensive, particularly far from the Caribbean, settlers in the Northeast found sweet relief in the production of maple sugar.

“It was the ‘poor man’s sugar,’” Penelope Jessop, vice president of the Androscoggin Historical Society, said about the early days of maple sugar.

Jessop has a small display at the historical society’s 93 Lisbon St. location featuring Native American artifacts underscoring their historic connections to maple syrup production. It includes a birch bark basket used for heating sap, which she acquired on loan from the Neptune family, an eastern Maine Passamaquoddy family renowned for their basket weaving.

“I thought that was really interesting because you don’t think of bark as a container full of fluid. But on the other hand, it’s wet, it’s not going to burn. I figured this was a great opportunity to show that too,” Jessop said.

The display, which will remain up until mid-April, also honors the late Ed Jillson of Sabattus’s Jillson Farm. Jillson was one of the leaders of Maine’s maple syrup scene over the past nearly 40 years.

Taps and spouts crafted out of metal during the early 1900s are on display at Merrifield Farm in Gorham. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

“His work ethic was so great and simply because maple was a big part of his life,” Jessop said. “It’s not a very big display, but it honors Ed and puts the Native American spin on it, which is a nice twist.”

By the mid-1800s, maple sugar and maple syrup production were a farming staple bordering on an industry. According to a Portland Daily Press brief on March 20, 1866, a Manchester, New Hampshire-based reporter for the Mirror and Farmer reported that a three-year experiment “found 4.5 gallons of maple sap equal to one pound of sugar.”

A month later, a Brunswick Times Record brief gave kudos to a Bethel man who collected enough sap in a week to make 488 pounds of sugar or, according to the same Mirror and Farmer reporter’s math, about 2,200 gallons of sap.

“If he sold it at 30 cents a pound, he will have made a good week’s work,” the brief stated.

Some $146 in a week’s work would have accounted for just under half of a year’s average income for a farmer back then. Maple sugar at about 30 cents a pound in 1866 would fetch about $5.80 a pound today considering inflation, but today’s demand puts the sweet stuff at about $20 a pound.

Obviously, a lot has changed, said Alan Greene of Greene Maple Farm in Sebago. Greene, MMPA vice president, is the eighth generation of maple producers in his family and is currently building a new sugarhouse next to his 1965-built sugarhouse.

“Before that, my father boiled in the driveway across the road,” Greene said. “And before that, our ancestors boiled on rocks down behind our barn. . . . It’s a U-shaped area where a pan would have sat on the rocks, and they had a fire underneath.”

Greene said the rocks are still there and his family continues to preserve the site, which his grandmother referred to as “boiling down in the pines” in her 1935 journal.

Maple producers began focusing on maple syrup over maple sugar as the price of beet and cane sugar fell and it became more prevalent up the Atlantic coast. Producers also found a “sweet spot” in the boiling process, Greene said, yielding syrups of a density that were shelf stable and did not ferment or settle out into sugar. Now regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, syrup has a “legal quality,” he said, with standards that producers shoot for.

While the syrup process continues to evolve with extraction and boiling technologies, it has become more erratic due to climate change. Maine Maple Sunday Weekend has almost always fallen on the midseason of sap running, with the frigid nights and warm days of spring being ideal, but producers cannot count on it as a rule anymore, Merrifield said.

Farmers made maple sugar molds out of wood, including this mold of a bible held by Lyle Merrifield. It is on display at Merrifield Farm in Gorham. Andree Kehn/Sun Journal

“We are seeing a huge difference in what we would normally call our typical season. Historically, most producers, even in the northern part of Maine, would start tapping, you know, mid-February and typically the sap would start running around the first part of March. Normally, we had a four- or five-week season progressing daily up across the state.”

Merrifield said northern Maine would sometimes produce syrup into the end of April or beginning of May, but “we’re not seeing that anymore.” He said one sugarhouse in Jackman began boiling sap in the first week of January before traditionally colder weather resumed and paused the process.

Nowadays, collecting sap in late April is rare. What was once a steady couple of months of sap running with a day or two pause due to weather has become a handful of micro-seasons, Merrifield said. There tends to be good enough weather for about four days of producing sap, then nothing for a brief period, and then a week or week and a half of moderate success.

Merrifield said technology often softens the blow of moderate or low sap production with many larger producers using vacuum systems to keep what sap there is running through the lines.

“I know some of the immediate people in my area are on vacuum and we’re still doing pretty well this season so far,” Merrifield said. “It depends on what your operation is, but there’s no question that things are changing a lot weather wise.”

Said Greene, “It’s amazing to me how much things have changed even in my generation, yet it’s still the same process. My father always liked to say that we take a very simple process and we make it look complicated. And it’s true, because we’re doing the same thing that has been done for hundreds of years. . . . The end product may be filtered a little better, and it may be a little more shelf stable, but in the end it’s still maple sugar, maple syrup. It still came from the tree, and we just took something that was naturally given and made it into something that we can all enjoy.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.