Sober bartending sounds like an oxymoron.

In fact, it’s a growing movement in hospitality, an employment sector that “comes in only second to construction as the highest substance use disorder in an individual industry,” according to Ben’s Friend’s national co-chair Hailey Hosler. The 10-year-old national nonprofit offers support to food and beverage workers who want to stop drinking.

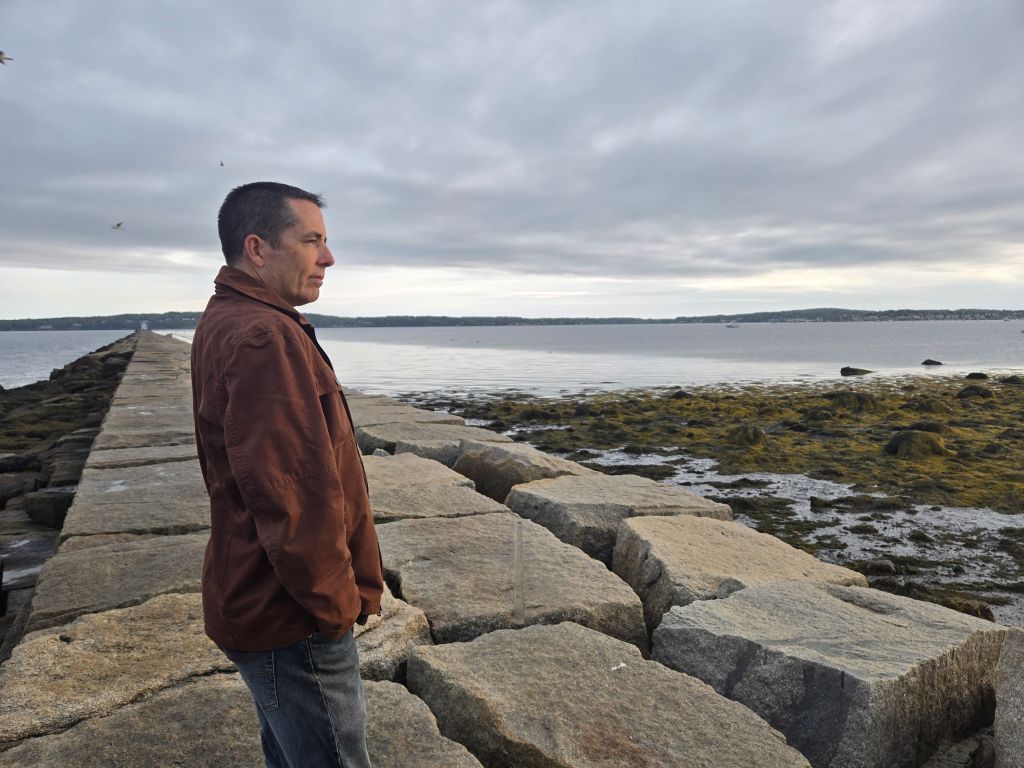

“It’s different, right? Because you don’t come across English professors who don’t read and you don’t come across fishermen who don’t eat fish, but I’m a bartender who doesn’t drink,” said Jeff McCool, who has been in the industry for 30-plus years and now works as a bartender and server at Primo in Rockland.

No matter what their line of work, people who struggle with addiction probably wouldn’t find swearing off drink a walk in the park. But hospitality workers face even steeper challenges. Every workday, temptation is right at hand: shots of bourbon, bottles of Imperial Stout, enjoyably sippable Negronis. Add to that a workplace culture that has traditionally been accepting — even encouraging — of drinking on the job.

“I’m willing to bet money that it’s not appropriate for you to take a shot of tequila at your desk,” Hosler said. “Almost everywhere I’ve bartended, it has been the norm to drink, not just with coworkers and while being in the industry, but actively, while working.”

Some bartenders, like the rest of us, use Dry January as an opportunity for a reset; they hit the pause button and stop drinking for the month. Others, though, have quit drinking, full stop.

COLD TURKEY

Everyone who gives up drink has a story to tell, and most seem to remember the day it happened. “November 10th, 2023,” McCool said. “That was my last drink. It’s a date that I’ll always remember because that was such a life-changing decision.”

McCool hadn’t hit rock bottom, by any means. He had a wife and kids. He had a job. He’d never been pulled over for driving drunk, and never gotten into a drunken brawl. For McCool, the realization he needed to stop came on an ordinary afternoon when he picked up his children at school. He was hungover. He felt “like hell.” Driving his kids home, he wasn’t connecting with them, or even talking to them.

“I thought, well, maybe I should stop this drinking thing that is taking up so much of my time and energy,” McCool said. “When I got home, I said to my wife, ‘I think I’m going to make a change.’ She started crying.”

For Sylvi Roy, bar manager at Central Provisions in Portland, the day was Nov. 1, 2023. She’d thought about quitting many times over 17 years in the industry. She had sober friends and family members, and she’d lost her beloved father to alcoholism. Roy had previously taken short breaks from drink, and her plan was to take up the No Drink November challenge. “I can do a month,” she told herself. On Halloween night, at the end of her shift at Crispy Gai, she took a last delicious sip from a pineapple daiquiri and steeled herself for the month ahead.

In just 30 days, though, Roy experienced “so many positive changes” that one month became two, two stretched into four, four slipped into a year, then two. Simply setting alcohol aside led to significant weight loss as well as gains in time, mental clarity and sound sleep. Her skin, hair and body improved, as did the balance in her bank account. She hasn’t looked back. “I’m a different person now.”

Via Vecchia lead bartender Daniella Solano has worked at bars and restaurants for 21 years, and as a brand ambassador representing premium whiskeys. Last July, her doctor informed her she was pre-diabetic. He prescribed medication and warned her she could have only one drink a week.

At the time, she was working at Room for Improvement in Portland. She’d already been thinking about just cutting out alcohol altogether, asking herself, “Where does drinking start to take up more space than it should? When does it go from, ‘This is fun’ to ‘Is it problematic?'”

Like Roy, after just a few weeks without alcohol, she experienced “an amazing shift.” She felt less bloated, less anxious and more present. A serious runner, she made “huge, huge personal gains” in her athletic performance. She hasn’t had a drink since.

Did Solano consider leaving the industry so that she wouldn’t be surrounded by the very thing she is trying to avoid? “Honestly, not even for a second,” she said.

ON-THE-JOB STRATEGIES

Bartenders gave several reasons for staying in the business despite ubiquitous temptation. It’s their career. It’s what they’re good at. They enjoy the work. It pays the rent, the mortgage, the dentist, the grocery bill.

“I really like the industry,” McCool said. “I like making drinks. I like creating cocktails and recipes. I like having that around still, without actually having a couple of them myself.”

For Hosler, easy access to stimulation was never the real problem. “When I wanted to get drugs, I would drive two hours at a time to get them. When I wanted to have a drink, I would find whatever place was open in whatever part of town,” she said. “The barriers were pretty meaningless.”

That said, working where alcohol is readily available, at least in the early days of recovery, “is generally not recommended in my own professional and personal opinion,” Colleen Garrick, Casco Bay Recovery director, People & Business Operations, wrote in an email. She adds that she was not speaking in her official capacity; she is a certified drug and alcohol counselor and in recovery herself.

But “recovery is not one-size-fits-all,” she continued, and suggested strategies including participating in a strong recovery program, finding a sponsor and “having an exit plan if cravings escalate.”

Sober bartenders have their own ways of coping. Some leave bars for jobs at restaurants. “We see a lot less binge drinking in restaurants. It’s more about the food,” Roy said. These bartenders treat alcohol as an ingredient in the drinks they create, rather than the star of the show. They focus on other aspects of their work.

“I’m really good at systems. I’m really good at education. I’m really good at offering an experience to guests,” Solano said. “There’s so much more to it than just the drinking.”

During educational wine tastings, sober bartenders take a sip, swish and then spit. Or they rely on their noses. “My nose is actually better than my palate anyways,” Solano said. Such in-house education sessions “provide such great education and information that they never make it a struggle for anyone who is not imbibing,” she said.

Some sober bartenders give themselves a little leeway, for instance straw-testing a cocktail — the industry term for dipping a straw into a drink, placing one’s thumb at the far end and tasting a few driblets to check that the drink is correctly made. “I don’t have a problem with myself having alcohol in my body in that way,” Roy said.

Strategies aside, “most talented bartenders know how to build a cocktail with their eyes closed,” Hosler said. “They could get away with never tasting again.”

WORKPLACE CULTURE

Arlin Smith, owner and general manager at Big Tree Hospitality (Eventide Oyster, Honey Paw, Town Landing Market and others), began drinking at 17. As a promising youngster starting out in professional kitchens, “I was handed drinks right on the line.”

Twenty years later, he got sober. By that point, “my choice to leave alcohol almost felt like it wasn’t a choice for me,” he said. “I have a daughter. I have a family. I have a business that takes care of so many people. I’m telling you — no bullshit, no lying —I just looked in the mirror and felt it all weighing on me.”

Does the hospitality industry foster a culture of overindulgence? There’s no single answer, but also no question that the work is stressful and physically demanding. “You’re going crazy for sometimes 8 hours, 9 hours, 10 hours at a time without a break,” McCool said. No wonder that at shift’s end — often late at night when bars are the only places open — restaurant workers seek to unwind with a drink — or three.

Hosler thinks it may be the other way around. “People ask me sometimes if being a bartender is what gave me an alcohol problem, and I answer ‘No, certainly not.’ I think I had it long before I ever found bars and restaurants. But the restaurant industry is a fabulous place to hide an addiction.”

Either way, alcohol is all around, whether it’s sneaking drinks during the workday (job performance doesn’t necessarily suffer, McCool said, because “you get good at it in a bad way”) or “shift drink,” the long-standing industry practice of one free or low-cost drink for employees after they’ve clocked out.

When Smith worked at Hugo’s, a now-shuttered Portland restaurant he later owned, shift drink was a cold Narragansett, a refreshing reward for line cooks who’d pushed through a hot, frenzied night on the line. Honey Paw and Eventide Oyster — and many other places — still offer shift drink, although Smith said he, his partner and his managers regularly revisit the policy.

“It’s not set in stone.” For now, though, Smith sees it this way: “We’re not going to be Big Brother in the room. We want you guys to police yourselves, to make your own healthy decisions.”

A CULTURAL SHIFT

Changes in the hospitality industry have made that easier.

Sober bartending is part of a decade-old movement reevaluating the “underbelly” of restaurant life as famously, or infamously, captured by Anthony Bourdain 25 years ago in “Kitchen Confidential.” Starting before the pandemic, and accelerating since, many in the industry have sought better workplace conditions. Employers have added health insurance and paid vacation and confronted sexual harassment. Employees have called attention to the mental health challenges of the business, have demanded better work-life balance — and are re-examining their relationship with drink.

“It’s a good time,” Hosler said. Industry people she knows who have been sober for decades tell her enviously, “‘You are getting sober at the coolest time.’ No one looks at you like you have three eyeballs. There are resources. There are fun things to drink. The shame aspect is really going away.”

Many employers are supportive, too, as is the case at Central Provisions, Via Vecchia and Primo, according to bartenders interviewed for this story, although Hosler said she has heard from bartenders who are thinking about giving up drink that they’re afraid they’ll lose professional credibility.

Smith said he’d look at a potential sober hire as a plus, as someone who must really know and love the business enough to want to stay in it despite the challenges, and who might nerd out on making mocktails. The former wine buyer for Hugo’s, now at the Michelin three-starred Eleven Madison Park in New York City, was sober, Smith said, “and he was the top seller of wine in my business.”

Said Hosler, “Every person gets better at what they do when they put down the drinking.”

CUSTOMER SERVICE

On the day that McCool decided to “make a change,” he didn’t know what shape that would take. Maybe he’d just cut back on drinking. Maybe he’d take a short pause. Maybe he’d go cold turkey.

But as time went on, “it became like a train going down the hill. After a month, this is an accomplishment at this point, right?” he said. “I just sort of rode that wave and kept doing it, and kept doing it, and it wasn’t easy by any stretch, but now it’s been two years and about two months without any drink.”

The other night at Primo, a customer asked McCool about a certain amaro (an Italian liqueur) on the beverage menu. “And I said, ‘That one is my favorite!’ And then I backtracked immediately and I said, ‘Well, it used to be my favorite.’ They saw that I had this awkward moment, and they said, ‘Why isn’t it your favorite anymore?'”

McCool told them he no longer drank. He told them he was sober. Then he added, “It’s delicious and you’re going to love it.’

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your Sun Journal account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.