State was active participant

in turn-of-the-century fight

against concentration of wealth

Presidential aspirant Bernie Sanders, who proudly boasts of being socialist, would have found his “populist” economic messages resonating with many Maine sympathizers marching in Labor Day parades in the late nineteenth and early years of the twentieth century.

While the theme of economic inequality, and that of too few people have too much power, are old themes which reach deep in state and national history, they were shouted more loudly than ever in the late 19th and early twentieth centuries. It was indeed a time when the nation had witnessed the unbridled economic transformation from an agricultural into an industrial society.

Cognizant of the economic transformation of the nation, President Grover Cleveland, in his message to a joint session of Congress in 1888, remarked that “As we view the achievements of aggregated capital, we discover the existence of trusts, combinations and monopolies, while the citizen is struggling far in the rear or is trampled to death beneath an iron heel. Corporations, which should be carefully restrained creatures of the law and the servants of the people, are fast becoming the people’s masters.”

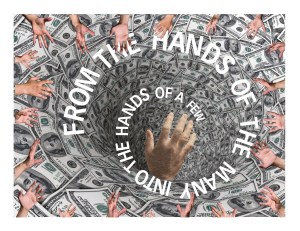

Locally, the graphic rise of inequality was echoed by Maine’s Labor Commissioner, S. W. Matthews, who, in 1889, summarized the significance of facts he presented to audiences, stating that they show “how unequal is the distribution of wealth of this country.” He declared that “the immense fortunes, which of late years have so rapidly multiplied have swallowed up the shares which an equal distribution would give to the masses. The wealth of this country is largely in a few hands.”

The issue of economic concentration and inequality were highlighted by the enactment of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890, and by the numbing disclosure that one percent of the population enjoyed more wealth than the wealth of the remaining ninety-nine percent.

The Populist Party of Maine (1891) echoed the sentiments of the national organization which declared that “The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these in turn despise the Republic and endanger liberty. …

The threat such concentration of wealth posed to the democratic process was noted with numbing regularity. In 1912, Woodrow Wilson graphically captured the pulse of concern about concentrated wealth and democracy when he noted that “the masters of the government of the United States are the combined capitalist and manufacturers of the United States. … Against a background of economic concentration, labor unrest, and rising disparities in income, he appointed a federal commission to investigate the tumultuous labor unrest in the nation. Among its conclusions:

Massed in millions at the other end of the social scale are fortunes of a size never before dreamed of, whose very owners do not know the extent or, without the aid of a intelligent clerk, ever the sources of their income…

The ownership of wealth in the U.S. has become concentrated to a degree which is difficult to grasp. The “rich,” 2 percent of the people won 35 percent of the wealth. The “poor,” 65 percent of the people, own 5 percent of the wealth. The actual concentration, however, has been carried much further than these figures indicate. The largest private fortune in the U.S., estimated at one billion dollars, is equivalent to the aggregate wealth of 2,500,000 of those who are called as “poor,” who are shown to own on the average about $400 each.”

A volatile expression of the the abuse of economic power can be gleaned from the tumultuous labor unrest that the nation witnessed as it counted 36,757 strikes and 1,546 lockouts, or 38,303 disputes between 1881 and 1905, and the employment of federal and state troops in over 500 labor disputes between 1877 and 1903.

Against such a background of a cauldron of seething economic conflict, former U.S. Commissioner of Labor, Carroll F. Wright, gave the Commencement Address at University of Maine, Orono, on the topic “Is There a Solution to the Labor Problem.” As he spoke, Maine workers had organized 212 unions into a state-wide body, the Maine State Federation of Labor with an estimated membership of 14,000 drawn from myriad workplaces and distributed over 50 cities, towns, and plantations.

In 1905 militant workers had organized the constitutional convention of workers which gave birth to the Industrial Workers of the World, an organization which declared that “the working class and the employing class have nothing in common’” and sought to “take possession of the earth and the machinery of production and abolish the wage system” thus emancipating workers from “wage slavery.”

Sentiment for radical unionism could be found in Maine. Earlier In 1903, local union delegates to the national convention of the American Federation of Labor sought unsuccessfully to introduce a resolution calling for the collective ownership of the instruments of production and distribution.

In 1900, the Maine Socialist Party was “born (in Rockland) with all the gusto of February weather along the Knox coast.” It shouted that “The great, overshadowing question — the question that is to be the issue of the coming election and will not (die) down until settled and settled right—is: Shall the trusts or the people rule this nation?”

It warned all those who would listen not to be misled: “it is not a question of “reforming” the present competitive system, that system is doomed, worn out, and like old clothes should be cast aside, but of adopting a new and better system of wealth production and distribution—the cooperative system. Shall a few irresponsible capitalists own, control and rule the nation or shall the nation, all the people, rise up their sovereign majesty and take over the trusts and administer industry in a just, scientific plan for the benefit of all.”

It was clear to the disciples of socialism that the business of the nation was too important to be left in private hands and that the capitalist mode of production was beyond redemption. Labor, the socialist argued was the source of all wealth but failed to receive the full fruits of its labor because because the means of production were privately owned.

The difference between what labor created and what it received was perceived to be “theft.” This Maine socialist clearly expressed a model of economic life dramatically at variance with the established views of a free market economy governed by inexorable self-regulating, self-correcting, “natural laws” of supply and demand which determined the “value” of labor and other economic activity. To Maine socialists, such views simply provided a philosophical shield which disguised and rationalized corporate greed and the exploitation of human and natural resources.

In 1902, the Maine socialists declared that the middle class was rapidly disappearing as a consequence of competition, and that the struggle had become a struggle between the capitalist class and the working class. To the socialists, economic power meant, in effect, control of all social institutions, while the profit motives sacrificed the lives of the working class and led to international rivalry and war among nations.

The state and its political machinery, they argued, simply legalized the exploitation of workers or otherwise serve the interests of the dominant class. To many observers of the time, the interests of private power, and the decisions of public bodies, were often one and the same. Such expressed fears have a contemporary ring to them. To ensue that that the working class received the full product of their labor, the Maine socialists called for the collective ownership of all means of transportation and communication and all other utilities as well as industries controlled by monopolies, trusts, and combines. The revenue from such industries were not to be used to reduce taxes on the property of the capitalists, but used exclusively to increase the wages and shorten the hours of labor of workers, and to improve services and lower rates to consumers.

The party further called for an eight-hour day on all state work be it under contract or not, and the ultimate abolition of contract work by the state. Included in their demands were the enactment and passage of a strong and effective employers’ liability law and the enforcement of child labor laws which the socialists maintained were made ineffective because parents were paid low wages. That being the case, the Socialists demanded that the state or municipality furnish clothing and food when necessary.

The state’s resident radicals also called for a system of public works which would provide employment and relief during periods of recession; equal civil and political rights for men and women; equal pay for equal work regardless of sex; that corporation pay their “just proportion of taxation;” that franchises and wild lands be taxed to their full market value; and passage of legislation that would permit cities and towns to own their own franchises if they so desired. They also called for the gradual reduction of the military forces of the state and denounced military education in any school in the state and the withdrawal f state aid to any school having such military instruction.

This catalog of demands serves as an index of steps towards the long-range economic transformation of society and the emancipation of workers from “capitalist slavery.”

The Maine architects of a new economic order were not looking for a cataclysmic proletarian upheaval, but sought to peacefully transform the economic order (unlike other strains of socialism). As a means of snapping the baneful link between corporate wealth and the political process, they endorsed grass roots political mechanisms such as the direct primary for nomination of candidates to state, legislative, congressional and county offices, a constitutional amendment calling for the direct election of national senators, and further called for the initiative, referendum, and the recall of elected officials. Such political reforms, shared by others, were viewed as antidotes, as political elixirs, to concentrated wealth and would served to save, purify, and extend democracy.

The embryonic Maine socialists placed candidates in the local, state, and national field from 1900-1916. Lewiston and Auburn, for example, were among the local communities that participated in the blueprint for a new economic order. The socialists organized branches in Lewiston-Auburn in 1901. Lewiston socialists chose 28-year-old O.A. Johnson, a Norwegian, as its president. The local press described him “as a thorough disciple of Carl Marx, Edward Bellamy and Eugene Debs.”

The local phalanx of socialists found themselves engaging in debates with the local press about socialism — which many equated with anarchism, atheism and violent revolution. Johnson wrote that “I know that a systematic attempt is being made to represent the socialist party as a lawless aggregation of anarchists with no respect for moral or legal codes, with an insane idea “to divide up” and make everything equal.”

Johnson, who became a candidate for municipal and state offices, became President of the Maine Socialist Party. In 1901 he remarked that “We realize …that so long as men have to fight one another in this condemnable competitive system (capitalism), in order to obtain the necessaries of life, there can be no true brotherhood among men, nor can the people admire the beauties of nature, or give birth to thoughts of higher things, for that cankerous serpent called hunger is daily staring them in the face, and the hardest problem for the working people to solve is: how to obtain a livelihood for themselves and children.”

Many were attracted to the socialist message, not for the intricacies of its fined- tuned theoretical analysis of economic life, but purely for its moral message. The American Cooperator, published in Lewiston, and “devoted to the ideals of a cooperative commonwealth,” was a pronounced illustration of this, as were the views of Lewiston’s Bradford C. Peck, head of the state’s largest department store in the state and author of the utopian novel, “The World a Department Store: A Story of Life Under a Coöperative System.” His Utopian novel was one of 68 such Utopian works published between 1865 and 1915 when the nation experienced the birth pangs of unchecked industrial growth. Middle class supporters such as dentists, lawyers, real estate brokers, clergy, etc. could be found within its ranks of the Maine socialist movement.

Some socialists of the state’s epicenter of the textile industry and shoe industry joined the growing labor movement in the city which boasted “over 3,000 persons” at the turn of the century.

In 1903 Lewiston renewed its Labor Day celebrations (Labor Day became a legal holiday in Maine in 1891). The local revolutionaries entered the municipal elections demanding that the city charter be amended to provide for the initiative and referendum and to provide for a municipal coal and wood yard to provide fuel at the lowest possible cost.

The local reformers also called for the ownership and control of the liquor traffic by the people, enforcement of child labor laws, that children in school be instructed of their rights under the child labor laws, and urged the extension of manual training in the public school system. They also called for the abolition of the contract system in all city work. Such work was to be done by direct employment of workers by the city subject to the conditions that the minimum wage for all municipal employees should not be less than $2 a day, and in no instances lower than the standard trade union rates, an eight-hour work day, only union labor be employed, and that supervisory officers would be elected by the employees themselves, subject to the control of the city administration and that the sick and disabled city employees be pensioned.

While Maine socialists failed at the polls, they along with others, widened the political debate by fueling discussion of the deleterious effects of unbridled corporate power and the threat of such concentration of power and wealth to the democratic process. The economic conditions of the nation invited criticisms of the established order and gave birth to third parties.

The nation was passing through a “populist” frame of mind, much like today. While the villain in the play remains the same, today’s “populism,” however, reaches beyond its base of farmers and industrial workers and reaches citizens in the nation’s suburbs and the white-collar spectrum of workers experiencing the seismic changes in their communities and lives as a consequence of liberalized trade policies and global competition and global markets.

Today, many who attracted to Bernie Sanders’ “socialism” are also attracted by a moral message rather than any intricate theories relating to the nature and evolution of socialism. They are attracted, as many were in the early twentieth century, by the moral indictment of an economic system that is increasingly perceived to be working for the few rather than the many.

Perhaps the Labor Day parades of tomorrow will contain a richer mosaic of work collars and represent a mirror image of the range of economic casualties and angry dissenters of contemporary society.

Charles A. Scontras taught at the University of Maine for 36 years He retired in 1997, but continues serve as a Research Associate at the University of Maine Bureau of Labor Education. He is the author of numerous books on labor in Maine.

Comments are no longer available on this story