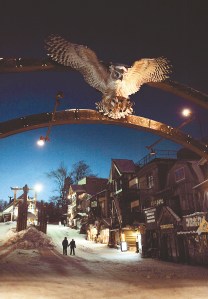

KUSHIRO, Japan — “Hoot, hoot.” As a low and heavy note echoed through a snow-covered forest in eastern Hokkaido, Japan, a large bird silently flew down the banks of a river. It was a Blakiston’s fish owl, also called the kotan kor kamuy (“god ruling the village”) by Ainu indigenous people. The owl flew into the darkness after catching a fish with its sharp talons.

More than 1,000 owls of the species inhabited Hokkaido in the early 20th century, but the figure stood at only about 70 four decades ago, according to the Environment Ministry.

Humans are to blame for the decline. Reasons include traffic accidents, electric shocks and changes to the owls’ environment through development. Thanks to the ministry’s efforts to set up nesting boxes and feeding stations, the owl population has now recovered to about 140. However, that figure is still far from being secure.

Blakiston’s fish owl inhabits mostly eastern Hokkaido and the northern territories. Designated as a national natural treasure, the bird is also listed in the Environment Ministry’s Red Data Book as a critically endangered species facing the risk of extinction in the immediate future. It is the nation’s largest owl, with a wingspan measuring over five feet.

At the ministry’s Kushiro-shitsugen (wetland) Wildlife Center, Keisuke Saito, 50, a veterinarian of the Institute for Raptor Biomedicine Japan, paused while performing an autopsy on a Blakiston’s fish owl believed to have been killed by a car.

“The liver has been ruptured. So have the kidneys,” the specialist said.

These kinds of autopsies are conducted with the aim of finding out how accidents occurred in a way that cannot be deduced simply by examining bodily injuries or using X-rays. The findings from these studies can ultimately help produce effective measures to prevent similar accidents from taking place.

“I cannot waste any death (of this bird),” Saito said with a stern look.

Local residents are also making efforts to protect the species. Farmers and fishermen are among those planting trees on a plot of vacant land in the town of Shibecha, eastern Hokkaido.

Blakiston’s fish owls nest in cavities of trees, such as Japanese oak and elm, that are over 100 years old. The tree-planting efforts are the first step of an activity that looks a century ahead.

Residents also began efforts to improve the environment in local rivers in 2014 in a bid to increase the number of fish the owls can eat.

“Protecting Blakiston’s fish owls means recovering our rich natural environment,” said local fisherman Katsuhiko Ohashi, 62. “This will eventually lead to protecting the town’s farming, fishing and other main industries.”

For the time being, the ministry has set a goal of increasing the population of the species to 200. In this northern region, people are continuing to make patient efforts to live together with these traditionally divine beings.

Comments are no longer available on this story