By allowing a very up-close-and-personal look at live cells in 3-D, the college’s new microscope is among the most sophisticated in Maine and holds the promise of fostering scientific breakthroughs.

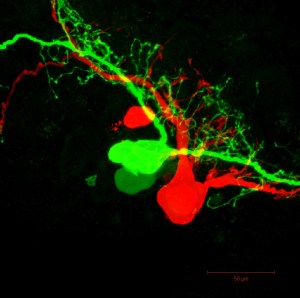

Many people – those without Ph.D.’s, anyway – might be scratching their heads and asking, “Just what am I looking at.” And they wouldn’t be alone. In fact, the microscopic images on this page might even raise the eyebrows of biologists and physicists.

That’s because the close-up pictures were made using a state-of-the-art microscope recently purchased by Bates College. More specifically, they were made with a computerized, laser-firing, fluorescence-producing, three-dimensional-image-making microscope with a price tag approaching $1 million. (The $791,480 purchase was covered by a National Science Foundation grant.)

But even more than what it does, it is what it might lead to that makes this microscope special.

Give insight into what causes birth defects? Check.

Tell us how exposure to chemicals affects the development of cells? Check.

Reveal ways to regenerate nerves, muscles and even whole limbs. Check.

The instrument is a behemoth, sitting on 20 square feet of property in the recesses of Carnegie Science Hall at the college’s Lewiston campus. Crafted by German lens maker Leica, it resides near some of the school’s other, expensive pieces of technology, including a scanning electron microscope.

But this one is unique, as assistant biology professor Larissa Williams explains. Typical microscopes, such as those in use since the 17th century, “work by distorting visible light (to) make an image large enough to see.” Pretty simple. It’s the same science behind a magnifying glass.

Rather than distort visible light before it hits our eye, Bates’ instrument scans minute areas of an object, picking up markers prepared by researchers, and then reassembles those scans.

“What this microscope can do,” says Williams, “is it can scan in (three) directions and then create a 3-D image.”

How does it see through objects? It begins with researchers coloring individual cells.

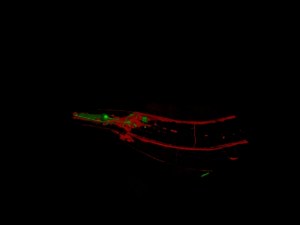

“We use, essentially, genetically modified organisms in our lab,” says Williams, who was one of four Bates professors who applied for the grant to purchase the new microscope. The researchers use a very colorful substance called green fluorescent protein from jellyfish. With it, researchers can genetically modify plants and animals to produce the protein themselves. Researchers can also inject dye directly into the spot they want to see.

Next, the researchers fire a laser at the specimen. “A laser is just pulsing light,” explains Williams, “and by doing that, it makes the protein really excited, like giving a kid sugar.”

As the fluorescent protein gets excited, it lets off light particles, which can be detected by the microscope even through thin layers of skin or tissue. Different proteins used by the researchers will result in different wavelengths of emitted light, or, in layman’s terms, the scientist can color code the things they’re looking at by using different markers, helping to differentiate the cells.

One of the most expensive elements of the new purchase, according to Williams, is the laser that is used to excite the protein. That and the software used to piece together the scans into a single image cost more than $100,000.

Considering what’s available today, including traditional microscopes, scanning electron microscopes, X-ray technology and other modern image-making devices, you might think this new toy is unnecessary. You’d be wrong, says Williams.

Because of the physical setup of the microscope and because of the non-invasive nature of the scans, researchers can actually leave living specimens under the scope for extended periods of time. This would be impossible with, say, the scanning electron microscope. Preparing specimens to be viewed by that instrument involves coating them in a hard material, meaning it kills living cells.

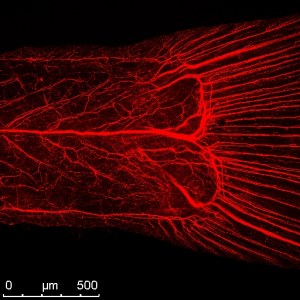

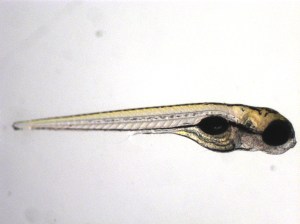

“What we’re enabled to do now, with this microscope, is follow things over time in living animals,” says Williams. “I study ear development in fish (which have) a green fluorescent protein in part of their ear. We raise the fish on the microscope and study the development over time.”

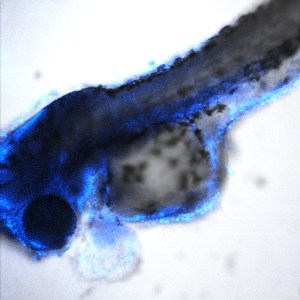

The instrument has another unique capability, according to Williams. While other microscopes, even state-of-the-art ones, produce images consisting of focused and unfocused light, resulting in some blur, “what a confocal microscope like the one we got does is it actually throws away all out-of-focus light. So you only get crisp images.”

This means “very, very well-resolved images,” she says.

Being able to get such a clear view of a biological system, in three dimensions, in real time, while keeping the specimen alive will offer insights for making advancements in many fields.

The applications for this new technology are manifold, as is attested by the work of the four scientists on the grant.

Williams’ research using the microscope to study ear development in fish could advance our understanding of what causes ear development disorders in humans, while her research into the zebra fish’s amazing ability to regenerate parts of its body, including its fins and heart, promises to advance efforts to regenerate human nerves and tissue.

Matthew Cote, an associate professor of chemistry, is using the microscope to investigate nanoparticles, “tiny particles found in all sorts of things,” including solar panels, says Williams. His work understanding the basic properties of nanoparticles could expand the growing use of nanoparticles to create higher performance photoelectric panels for solar energy harvesting.

Travis Gould, an assistant professor of physics, is “trying to better understand the physical properties of fluorescent dye for the sake of other researchers employing this new technology. His research will likely lead to even greater clarity and resolution of magnified biological imaging.

And Nancy Kleckner, associate professor of biology and neuroscience, injects fluorescent dye into snail neurons to better understand how our own brain is modeled, and into zebra fish neurons to understand the role those neurons play in the zebra fish’s regeneration abilities.

Naturally, there are also the academic applications. Already “the students are getting hands-on use of this machine” in the upper-level biology and physics classes, according to Williams. “Fortunately,” she adds, “this machine is built in a way that it’s very hard to break.”

The advances those students may go on to make in their lifetimes are incalculable.

“This is a game changer,” Williams says of the new machine. Its wide-ranging implications for human health are a large part of the reason that the researchers received the grant. And, per the stipulations of that grant, the scientists are expected to carry out research using their new tool.

While there is some incredibly advanced microscopy work also being done at the University of Maine, Bates’ new microscope is one of only two of its kind in Maine. The other is located at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor.

In fact, says Williams, the Bates researchers had help on their grant from colleagues at Bowdoin College, excited by the prospect of being able to travel up from Brunswick to use the new device. In terms of commercially available microscopes, this is the newest and most modern in the state.

“Bates has just become a much better institution because of this. This has elevated our ability to engage students and to train them in cutting-edge research.”

Max Mogensen is the owner of Anchor Arts + Communication in Portland.

Comments are no longer available on this story