Send questions/comments to the editors.

Read the series: How homelessness impacts Maine

An occasional series examining homelessness in Maine.

-

Cities, towns and the state are struggling to find answers. Some may already exist.

Cities, towns and the state are struggling to find answers. Some may already exist. -

People age 65 and older represent the fastest growing group of homeless. 'We’ve had people in their late 80s, early 90s who are living in their car.'

-

List of local service agencies accepting donations to help the homeless and at-risk populations in Maine.

List of local service agencies accepting donations to help the homeless and at-risk populations in Maine.

-

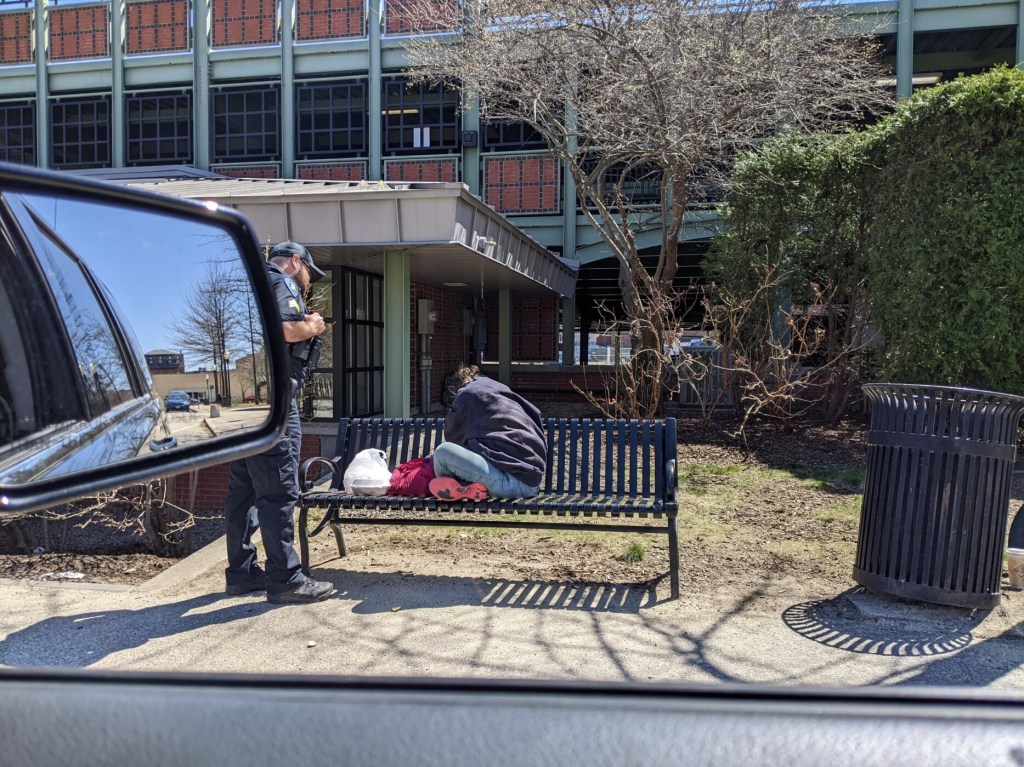

May 1, 2023Lewiston police have been employing various programs to keep the peace between business owners and the homeless. Their efforts have been paying off, according to most, although many business owners remain wary.

May 1, 2023Lewiston police have been employing various programs to keep the peace between business owners and the homeless. Their efforts have been paying off, according to most, although many business owners remain wary. -

May 4, 2023Homeless say they are feeling the heat as the city presses its Neighborhood First initiative.

May 4, 2023Homeless say they are feeling the heat as the city presses its Neighborhood First initiative. -

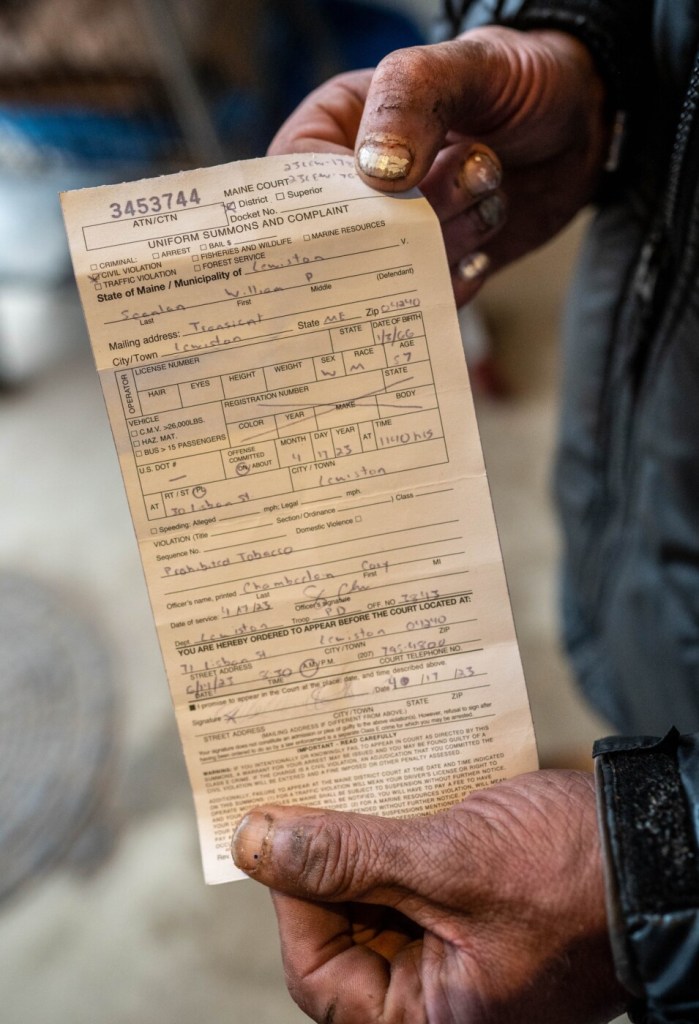

April 29, 2023Local police agencies are grappling with a new protocol established by the Office of the Maine Attorney General that calls on authorities to not charge homeless people with minor crimes but instead focus on connecting them with service providers who may be able to help.

April 29, 2023Local police agencies are grappling with a new protocol established by the Office of the Maine Attorney General that calls on authorities to not charge homeless people with minor crimes but instead focus on connecting them with service providers who may be able to help. -

May 1, 2023Over the past year, Sarah Juliano has gone from living at a homeless encampment in Waterville to now recovering at a sober house in Winthrop. All photos by Morning Sentinel staff photographer Michael G. Seamans.

May 1, 2023Over the past year, Sarah Juliano has gone from living at a homeless encampment in Waterville to now recovering at a sober house in Winthrop. All photos by Morning Sentinel staff photographer Michael G. Seamans.

-

March 11, 2023Many of them lack a stable, supportive family, and end up creating their own 'family' on the street with other homeless youths.

March 11, 2023Many of them lack a stable, supportive family, and end up creating their own 'family' on the street with other homeless youths. -

March 6, 2023Educators and homeless advocates are growing increasingly alarmed by a surge in the number of homeless youth.

March 6, 2023Educators and homeless advocates are growing increasingly alarmed by a surge in the number of homeless youth. -

March 6, 2023In her own words, a Lewiston homeless woman who helps other homeless people talks about life on the street.

March 6, 2023In her own words, a Lewiston homeless woman who helps other homeless people talks about life on the street. -

March 5, 2023

March 5, 2023 -

The law is intended to provide homeless students the same educational opportunities as housed students by removing any barriers to learning.

The law is intended to provide homeless students the same educational opportunities as housed students by removing any barriers to learning. -

March 6, 2023The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act defines homeless youths as 'individuals who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.'

-

January 16, 2023Unforeseen circumstances, and suddenly a Lewiston couple find themselves without a secure place for themselves and their child.

January 16, 2023Unforeseen circumstances, and suddenly a Lewiston couple find themselves without a secure place for themselves and their child. -

January 16, 2023Those who interact most closely with the homeless say it's a misconception that they don't want to work or try to help themselves.

January 16, 2023Those who interact most closely with the homeless say it's a misconception that they don't want to work or try to help themselves. -

January 16, 2023Over the course of several months, Morning Sentinel photographer Michael G. Seamans captured images of people living at a homeless encampment along the Kennebec River, and came to learn his assumptions about them were wrong.

January 16, 2023Over the course of several months, Morning Sentinel photographer Michael G. Seamans captured images of people living at a homeless encampment along the Kennebec River, and came to learn his assumptions about them were wrong. -

January 14, 2023Morning Sentinel photographer Michael G. Seamans captured the photographic journey of homeless people living at an encampment in Waterville, some of whom also work jobs, over the past several months. All photos are by Seamans.

January 14, 2023Morning Sentinel photographer Michael G. Seamans captured the photographic journey of homeless people living at an encampment in Waterville, some of whom also work jobs, over the past several months. All photos are by Seamans.

Local advocates say the number of adults, families and children experiencing homelessness has rapidly increased in the last year as Maine’s housing crisis persists.

There are more people in search of places to live than available units. As demand has grown, so too have prices and evictions.

Homelessness comes in all forms. There are those who are widely visible, living in camps and walking the streets of downtown Lewiston and Auburn with all of their possessions in hand.

But more often, people, especially families, struggle with homelessness quietly, away from the public eye. They stay with friends and family, live in hotels or create unconventional shelters – anything which puts a roof over their children’s heads.

The Sun Journal spoke with three homeless families in Lewiston-Auburn to share their stories of heartache and resilience.

One family lives in a retrofitted school bus. Another spends each night in a shelter. The third has moved half a dozen times in the past 16 months.

These are their stories.

-

December 20, 2022Father of three says his family has been constantly on the move as he tries to save money from his job for a permanent place to live.

December 20, 2022Father of three says his family has been constantly on the move as he tries to save money from his job for a permanent place to live. -

December 20, 2022Single father of two is slowly turning a bus into a home for his family. Up next, when his disability check allows: a shower.

December 20, 2022Single father of two is slowly turning a bus into a home for his family. Up next, when his disability check allows: a shower. -

December 20, 2022Among all the challenges of being homeless, the inability to cook their own meal and enjoy it together might seem small. But for the tight-knit family, it's everything.

December 20, 2022Among all the challenges of being homeless, the inability to cook their own meal and enjoy it together might seem small. But for the tight-knit family, it's everything.

“There was ice forming on the inside of our tent and when it would snow, we’d have to sleep in shifts so we could go out and shovel snow off the tent, so it wouldn’t collapse on us.”

Those words come from a 30-year-old homeless woman in Lewiston, who has been living in a tent and on the streets for four years. She’s among thousands of homeless people in Maine who need shelter as the harsh winter months get underway. Federal estimates earlier this year recorded the highest number ever of homeless people in the state — 3,455 — even as officials acknowledge the numbers are underreported and escalating costs are increasing the number of vulnerable Mainers.

The Sun Journal, Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel examine the causes, impacts and solutions to homelessness in Maine with an occasional series over the winter months. In the first installment, we look at how homelessness is visible in our central Maine communities amid the rising number of people without a stable home.

-

December 8, 2022Escalating costs for housing, food and fuel have officials especially concerned as cold weather sets in and as estimates grow for people unable to find stable housing.

December 8, 2022Escalating costs for housing, food and fuel have officials especially concerned as cold weather sets in and as estimates grow for people unable to find stable housing. -

December 5, 2022Steven York, 59, is living in Bread of Life Ministries' Veterans Shelter in Augusta and works five days a week at Veterans Affairs Medical and Regional Office Center at Togus.

December 5, 2022Steven York, 59, is living in Bread of Life Ministries' Veterans Shelter in Augusta and works five days a week at Veterans Affairs Medical and Regional Office Center at Togus. -

December 5, 2022The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has provided data since 2007, based on estimates from service providers who seek to count people in homeless shelter, people in communities without shelter and more considerations.

December 5, 2022The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has provided data since 2007, based on estimates from service providers who seek to count people in homeless shelter, people in communities without shelter and more considerations. -

December 5, 2022The Sun Journal and Kennebec Journal captured views of homeless people as winter sets in across the region.

December 5, 2022The Sun Journal and Kennebec Journal captured views of homeless people as winter sets in across the region.

Comments are no longer available on this story