MINOT — You’re a private in the 3rd Maine Regiment in the Civil War. You march 20-30 miles at a time. You’ve probably ditched the uncomfortable knapsack the Army issued. After the 20th mile of marching, it became unbearably uncomfortable.

You have an A-frame “dog tent.” Most of the time, you ask another private to share it with you to conserve warmth, because, even in the South, winter nights are freezing. You also have a gum blanket, rubberized on one side. You lie on the ground to help you keep warm-ish at night.

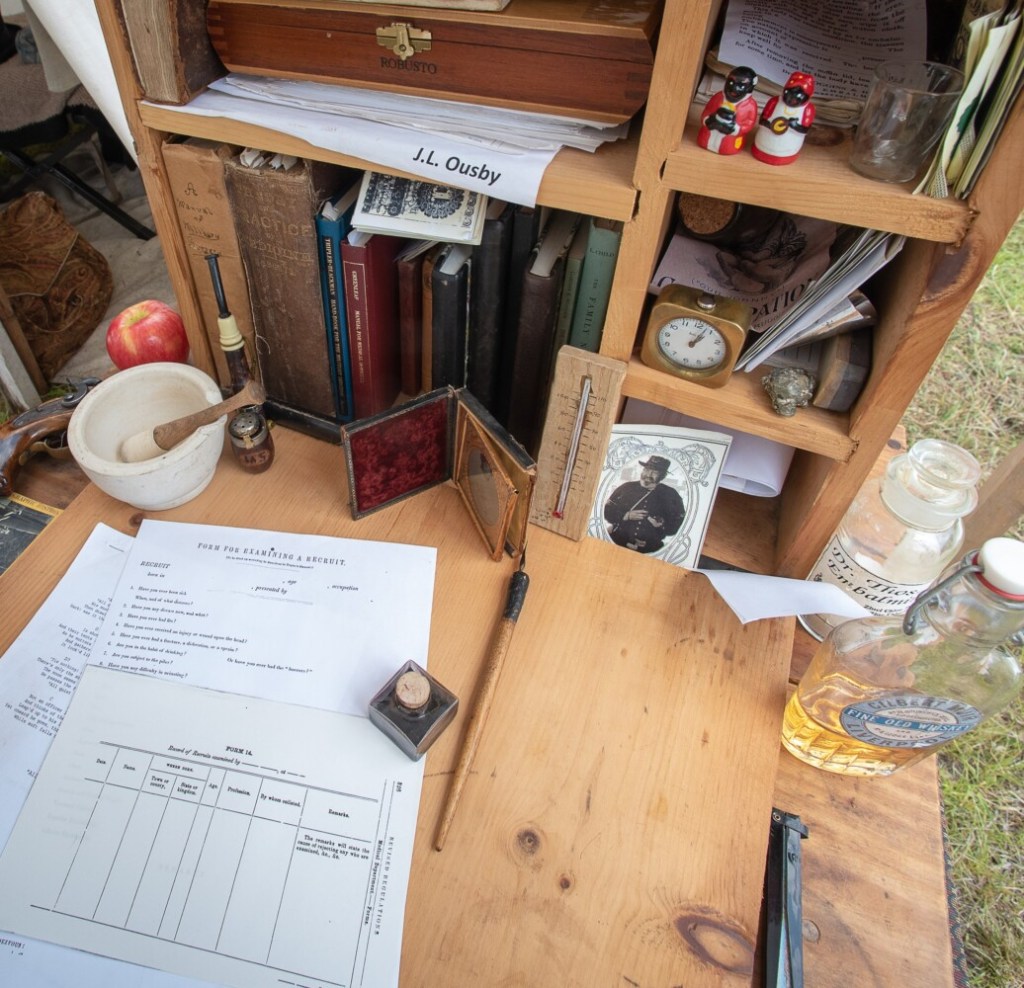

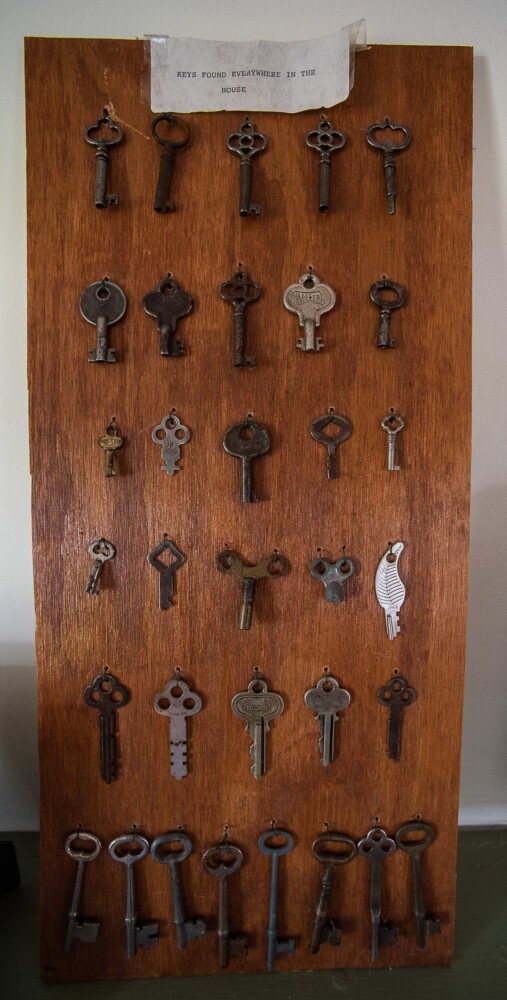

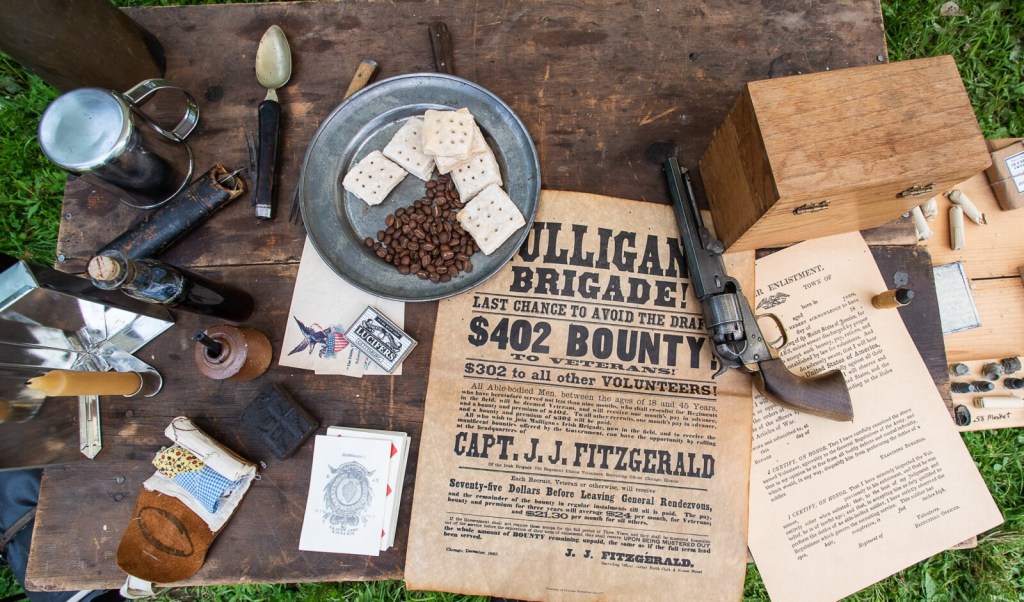

Scenes from Saturday’s Civil War Encampment at the Minot Historical Society. Russ Dillingham/Sun Journal

You have a canteen, a cartridge box containing 60 rounds of ammunition for your musket, a haversack for your possessions, three days’ worth of rations consisting of a bag of dried beans, salted pork, hardtack (a kind of biscuit) and, if lucky, an apple plucked from an orchard during the march into camp.

When you aren’t in battle, you spend your time drilling. You wake up, and drill. You drill again, and then you drill some more.

“Privates mustered up and drilled all day long,” said 3rd Maine Company re-enactor Raul Pinto. “It was a part of camp life. It was drilling, drilling and more drilling. The Civil War army had to work just like today’s Army. You hear a command and you do it without thinking.”

Pinto was among the Union Army soldiers and officers who set up camp in back of the Minot Historical Society on Saturday to re-enact the lives of Civil War soldiers, a living account of what life was like for Yankee soldiers.

You were always waiting for battle. Sometimes, engagement would come quickly. On your way to camp, you’d hear gossip that there was engagement happening up ahead. According to Pinto, you’d go in hungry and tired, but you just did what had to be done.

And there was a good chance you’d be shot. And that’s where surgeons came in.

Scott Scroggins, a Civil War re-enactor from Lisbon Falls talks with visitors about how doctors had no idea about infections and how their practices often caused more harm than good. Russ Dillingham/Sun Journal

“The biggest difference between then and now: They knew nothing about germs,” said Scott Scroggins, a re-enactor from Lisbon Falls. “Germs hadn’t been invented yet, which is why twice as many people died from disease as died from gunshot wounds.”

Scroggins said a few myths have taken hold surrounding amputations. Chloroform and ether had both been around for 15 years by the time of the Civil War. The whole “biting a bullet” trope is pure Hollywood. Amputations were the only major operations Army surgeons performed.

Step one. Cut through skin and move it back. Step two, use a larger knife to cut through muscle mass. Step three, a surgical retractor goes around the bone and muscle mass is pulled as far back as possible. You cut as close to that as you can. Step four, you smooth off edges of the bone, especially in a leg; the more meat you can get between the bone and the end of that stump that will become the artificial leg means less long-term pain. Stitch it all up, suture the arteries. Done.

Thaddeus Hildreth served as surgeon for the 3rd Maine.

Whitney Buker said this year is the third that the Minot Historical Society has hosted a living history event. It’s free and open to the public. The soldiers will conduct drills and mock battles throughout the weekend.

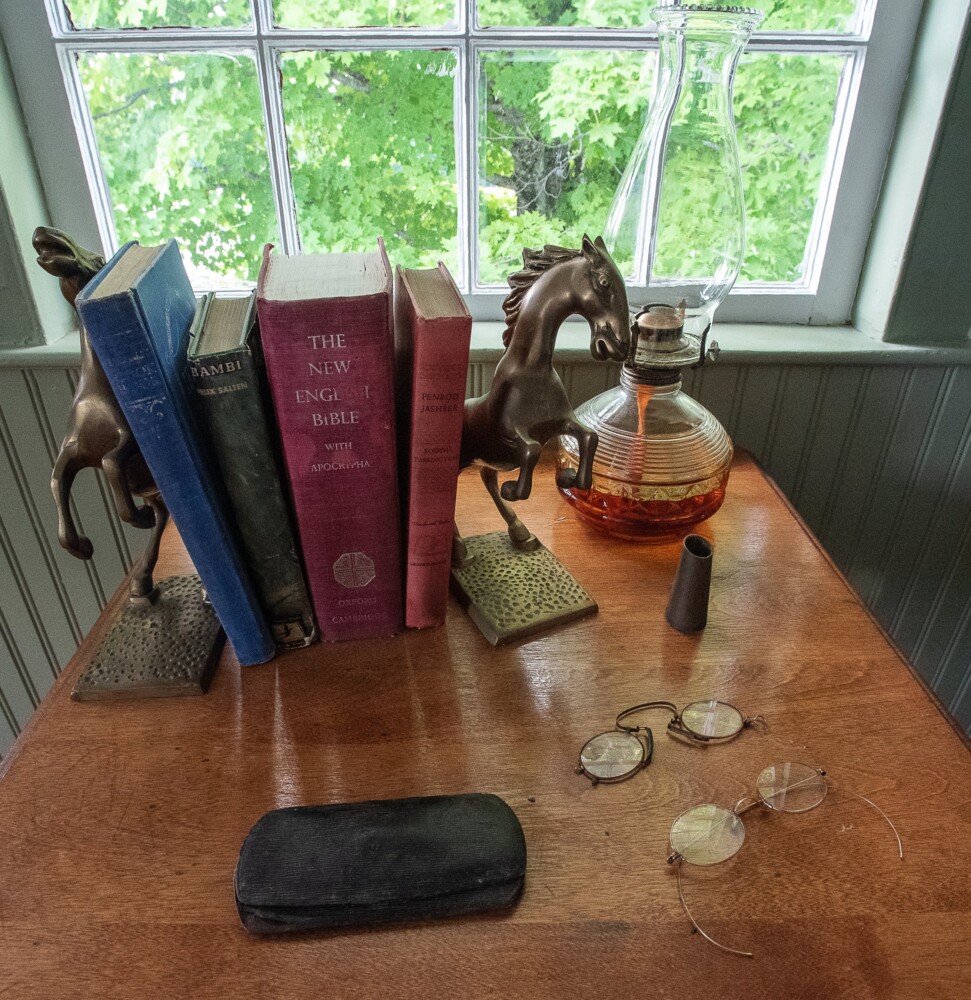

“We at the Historical Society still think it’s very relevant to think about the past,” Buker said. “And so we wanted to share that as a living history. With our parsonage, we thought it was a good location to have everybody come to visually see, interact and learn about the Civil War.”

Julian Kemp, right, listens to his sister Ari, back-to with hat, talk with their mother, Sarah Kemp, as they all, including brother Elijah, bottom, try on Civil War-era clothing during Saturday’s annual encampment at the Minot Historical Society. Russ Dillingham/Sun Journal

She added, “It shows you about how life back then was far different from now, and how family was so important and local government. Everybody as a community banded together and supported their country.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story